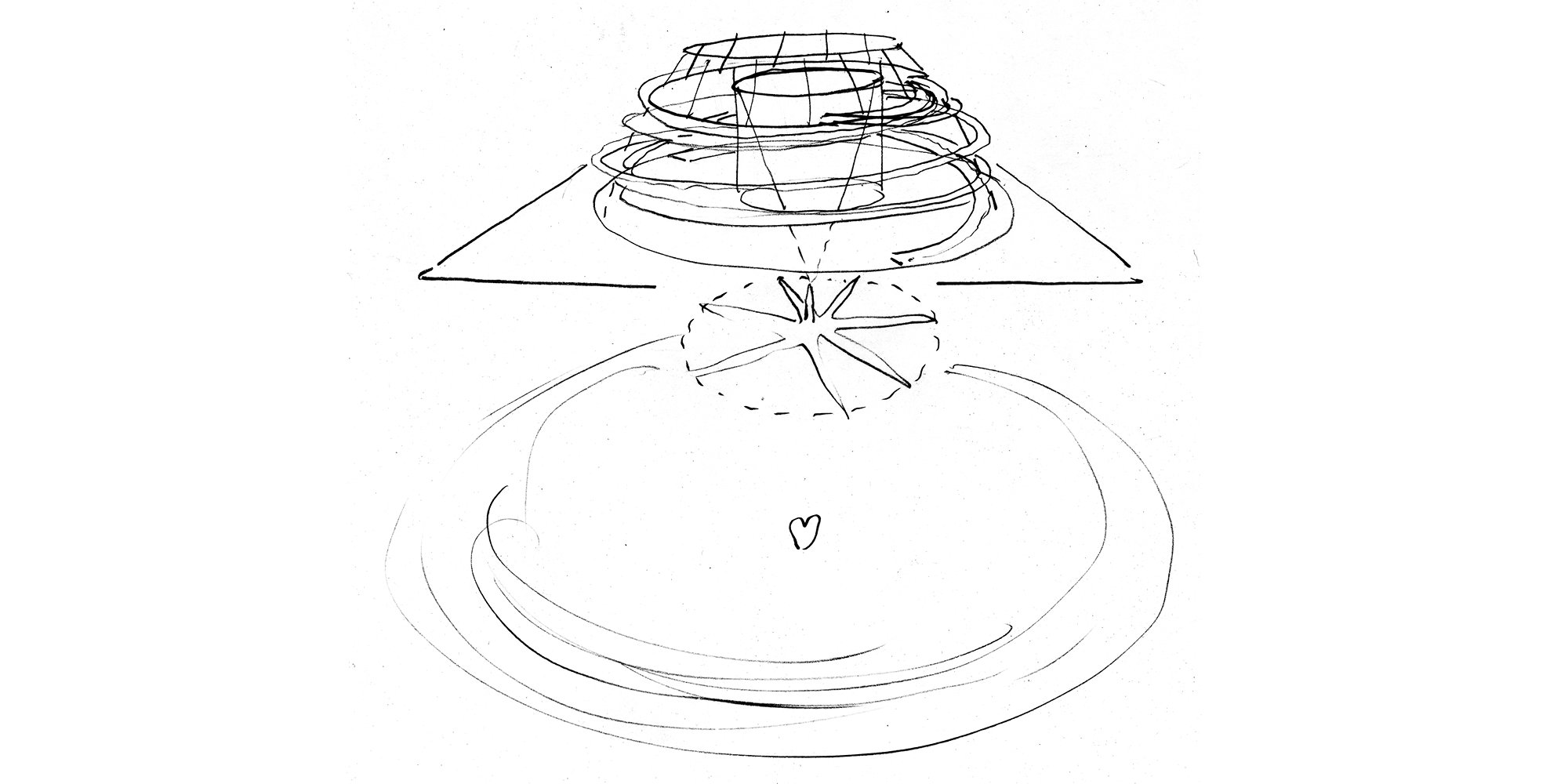

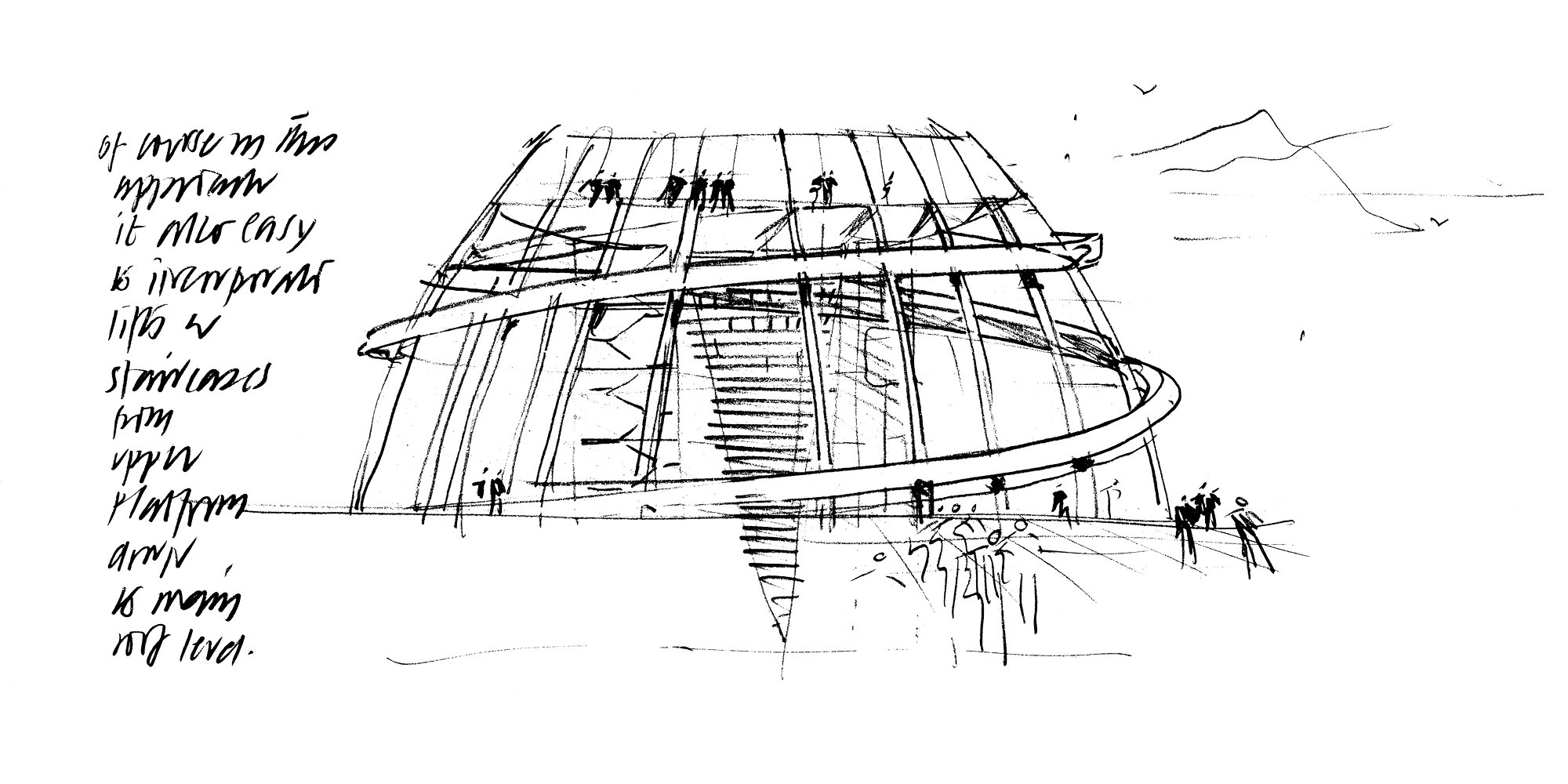

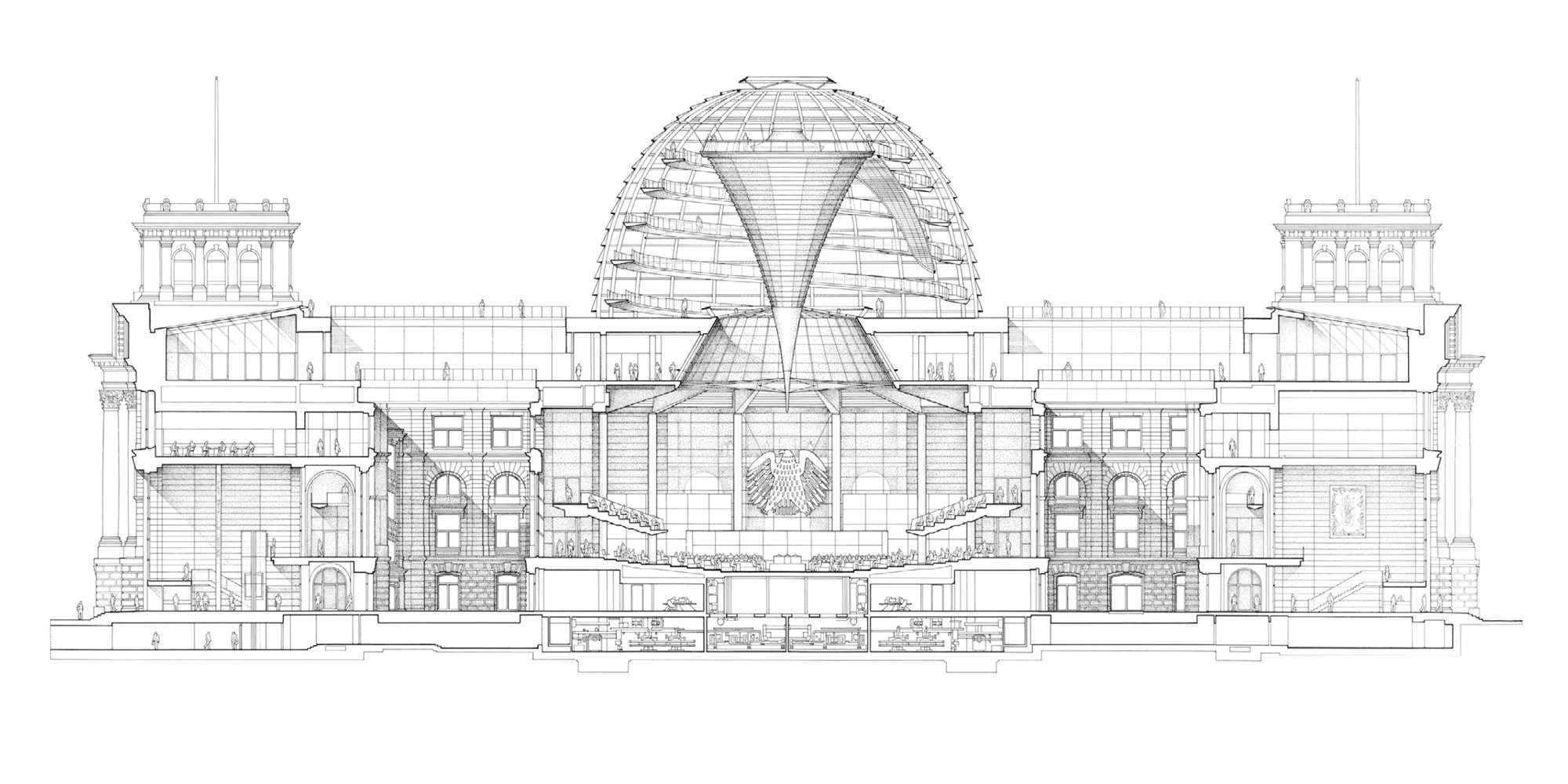

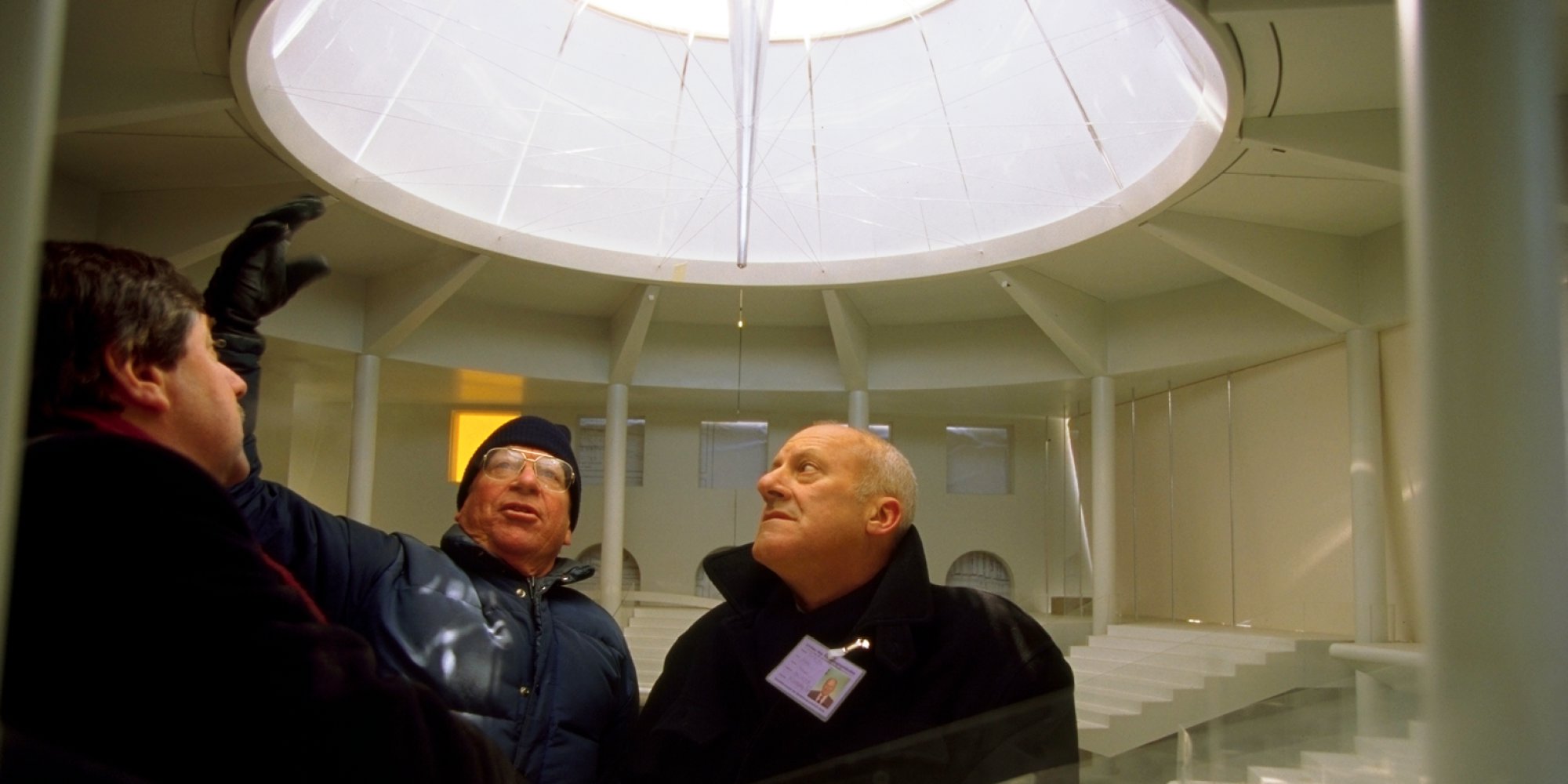

April marked twenty-five years since the practice completed its transformation of the Reichstag in Berlin. Stefan Behling, Head of Studio at Foster + Partners, describes what it was like to be part of the team that worked on the major redevelopment project, during the early stages of his career.

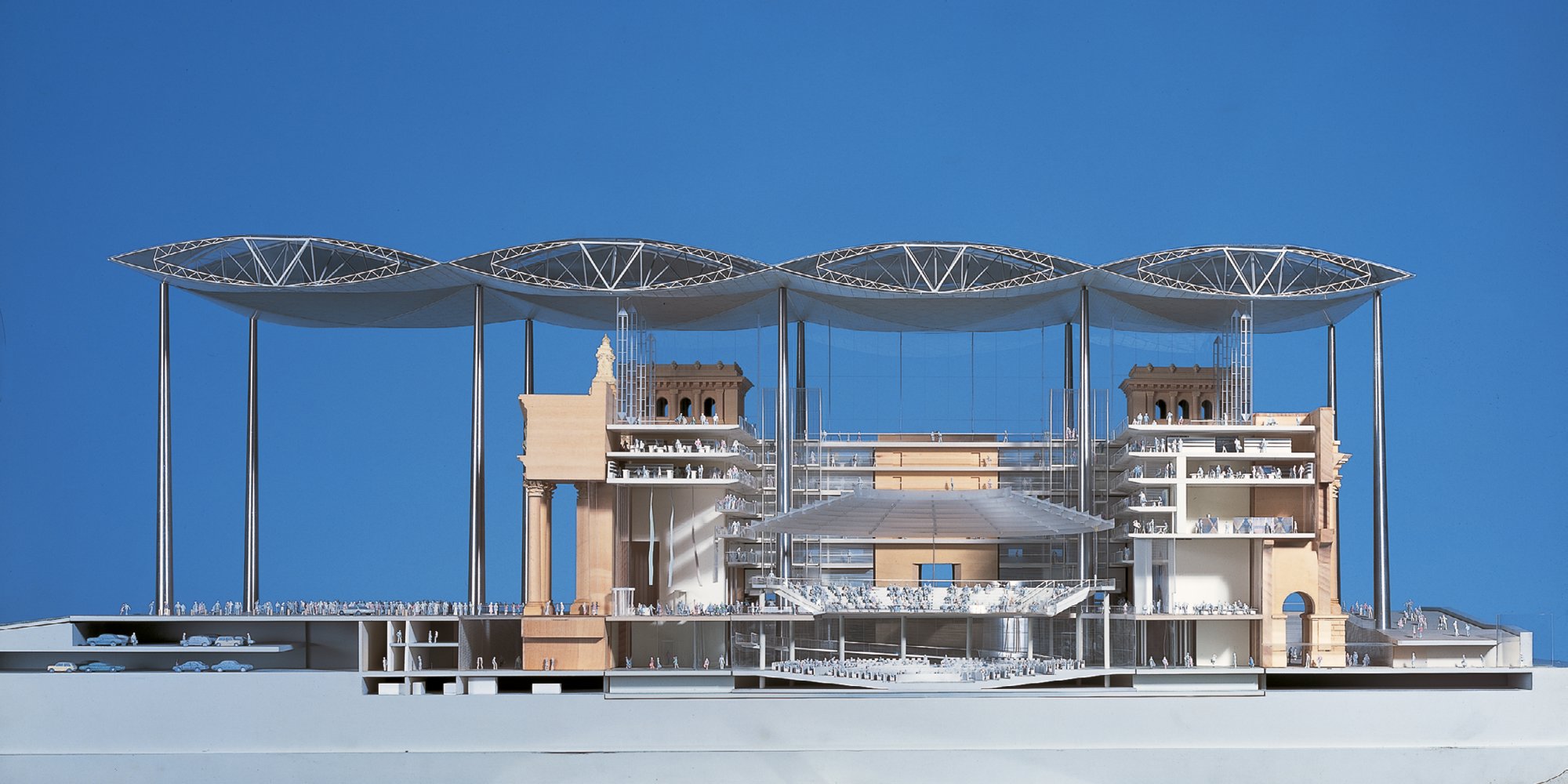

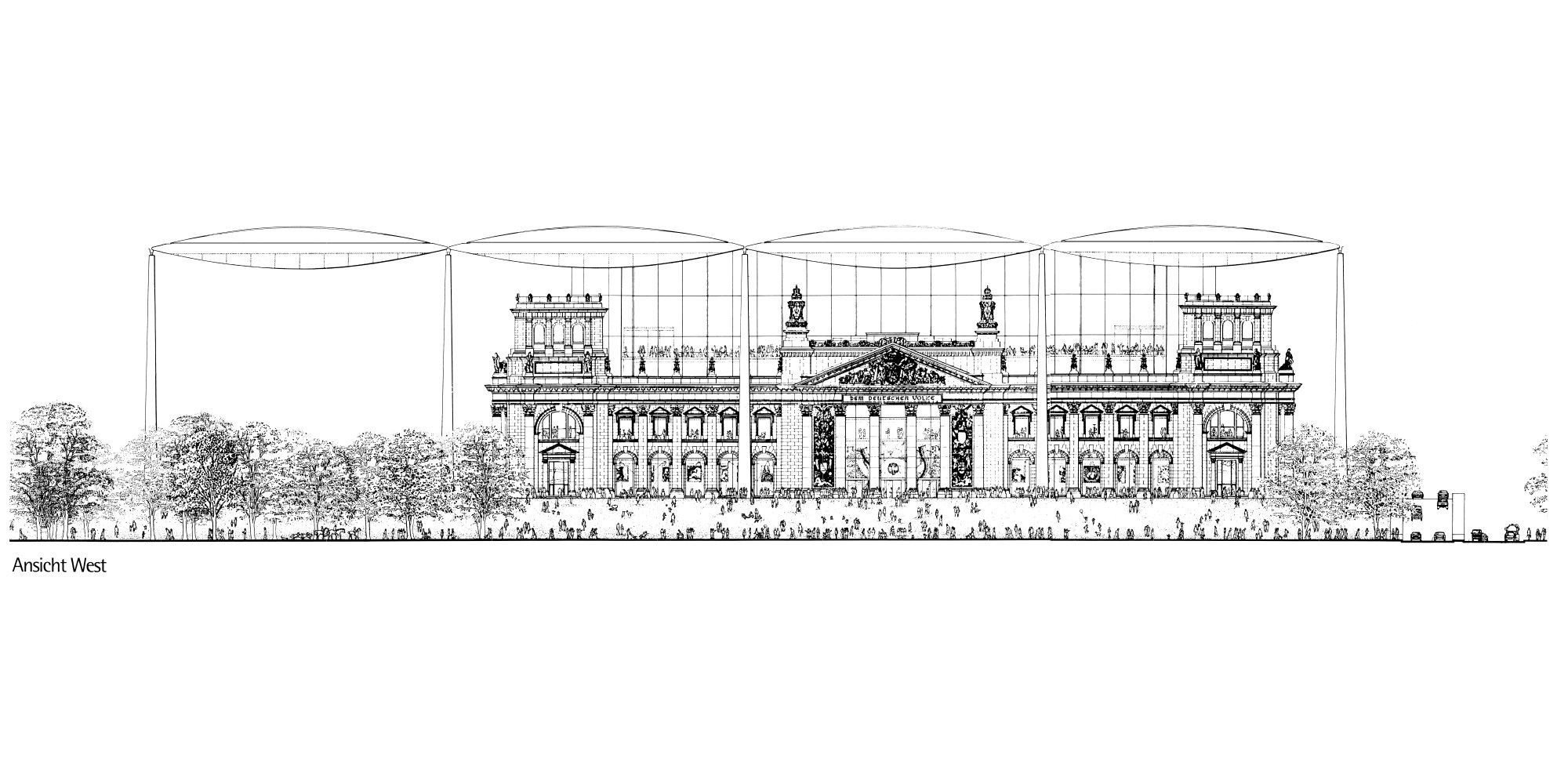

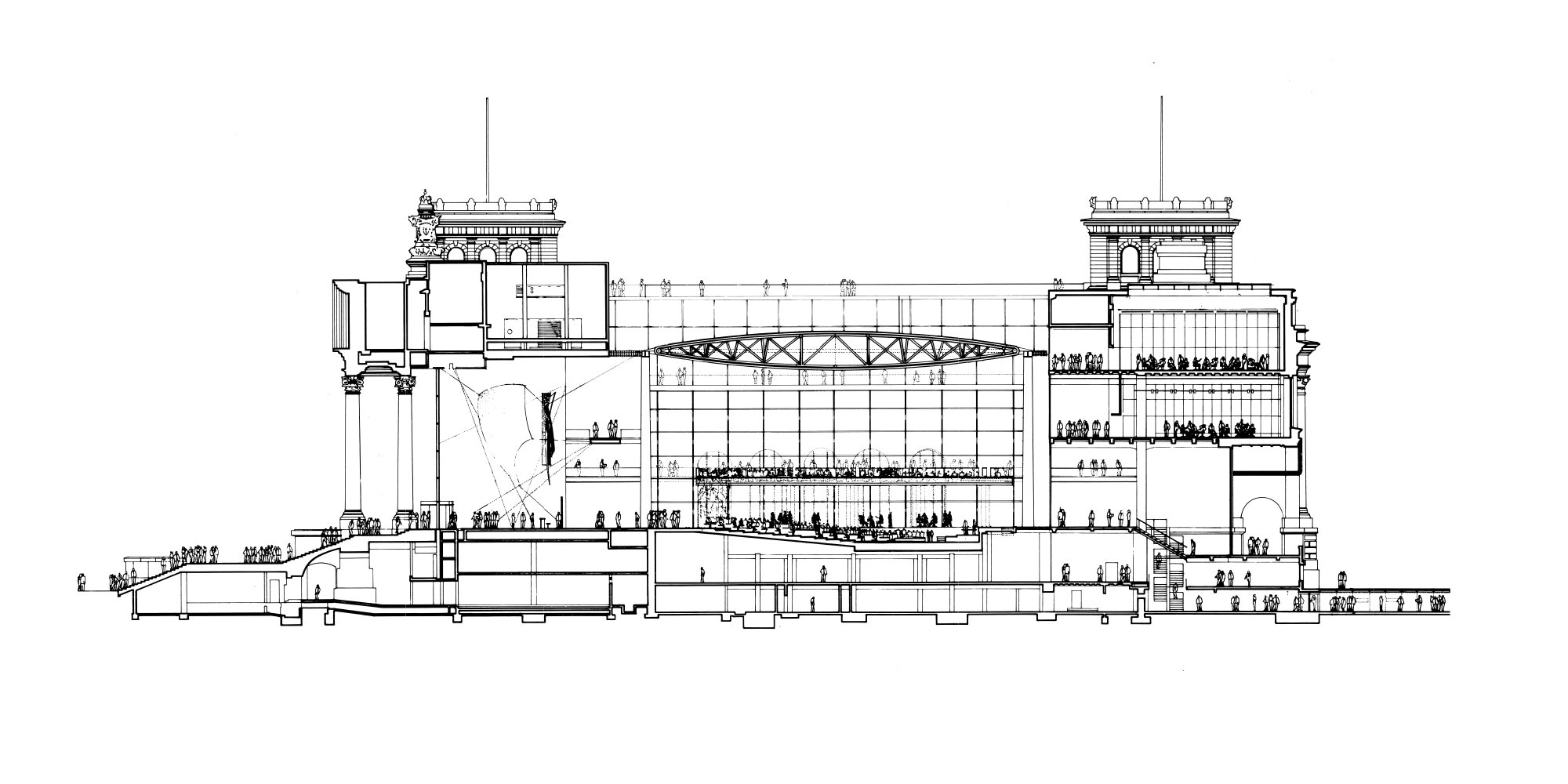

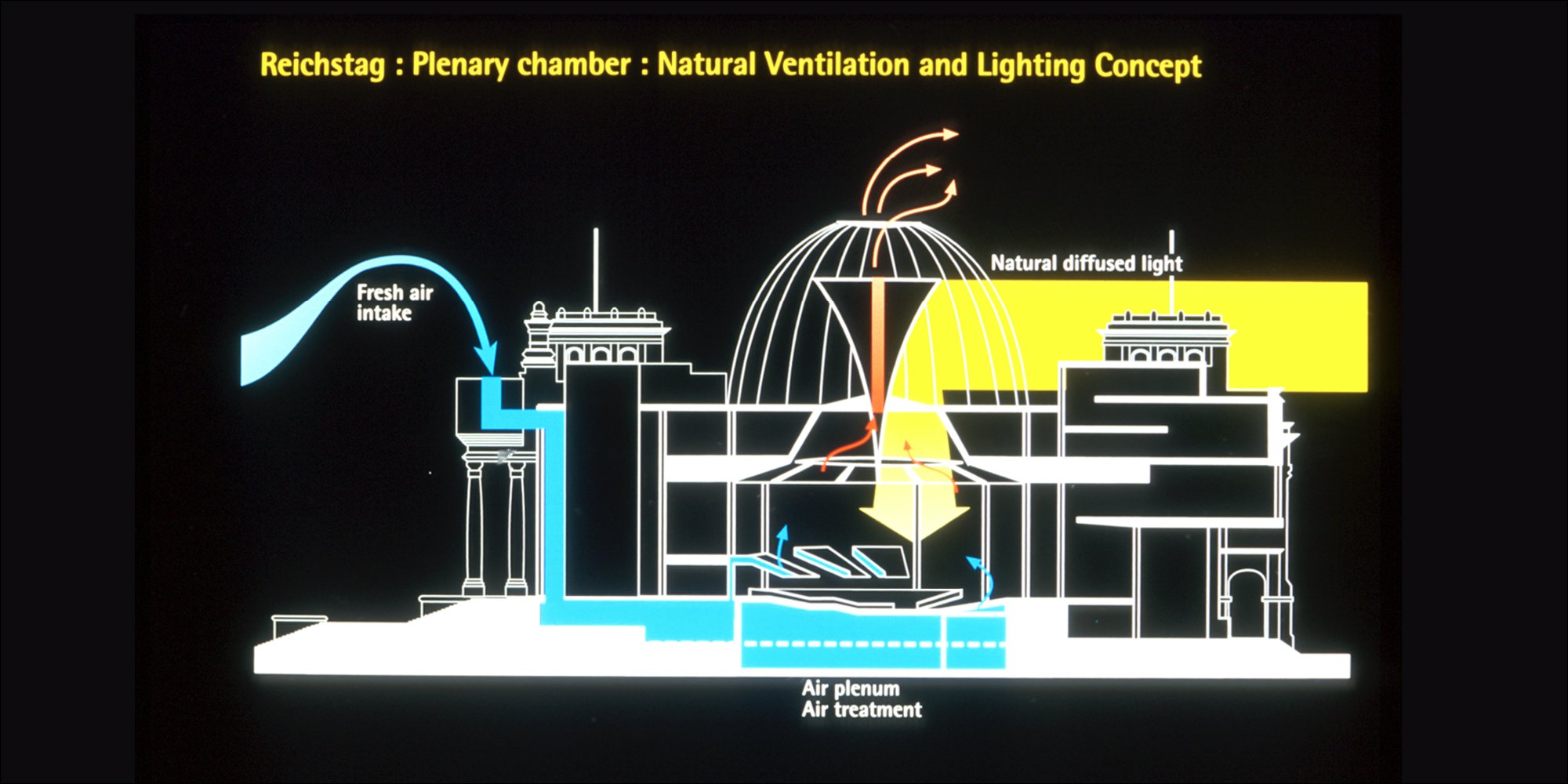

The reconstruction takes cues from the original fabric; the layers of history were peeled away to reveal striking imprints of the past – stonemason’s marks and Russian graffiti − scars that have been preserved as a ‘living museum’. But in other respects, it is a radical departure; within its heavy shell it is light and transparent, its activities on view.