Landscape architecture has long understood the importance of sustainable and ecological design. In a roundtable discussion with +Plus, the Foster + Partners' Urban Design and Landscape team consider how landscape and architecture are closely connected - throughout our built environment and within the collaborative ways that we design it.

‘Today, landscape has more to teach architecture than architecture does landscape.’ This recent remark by Kenneth Frampton, architectural critic and historian, registers the concerns felt today by many professionals in the built environment. How can we design sustainably in a climate and biodiversity crisis? How can we endorse and improve the design of public space? And how can we connect people with their environment – a relationship which the modern world so often severs?

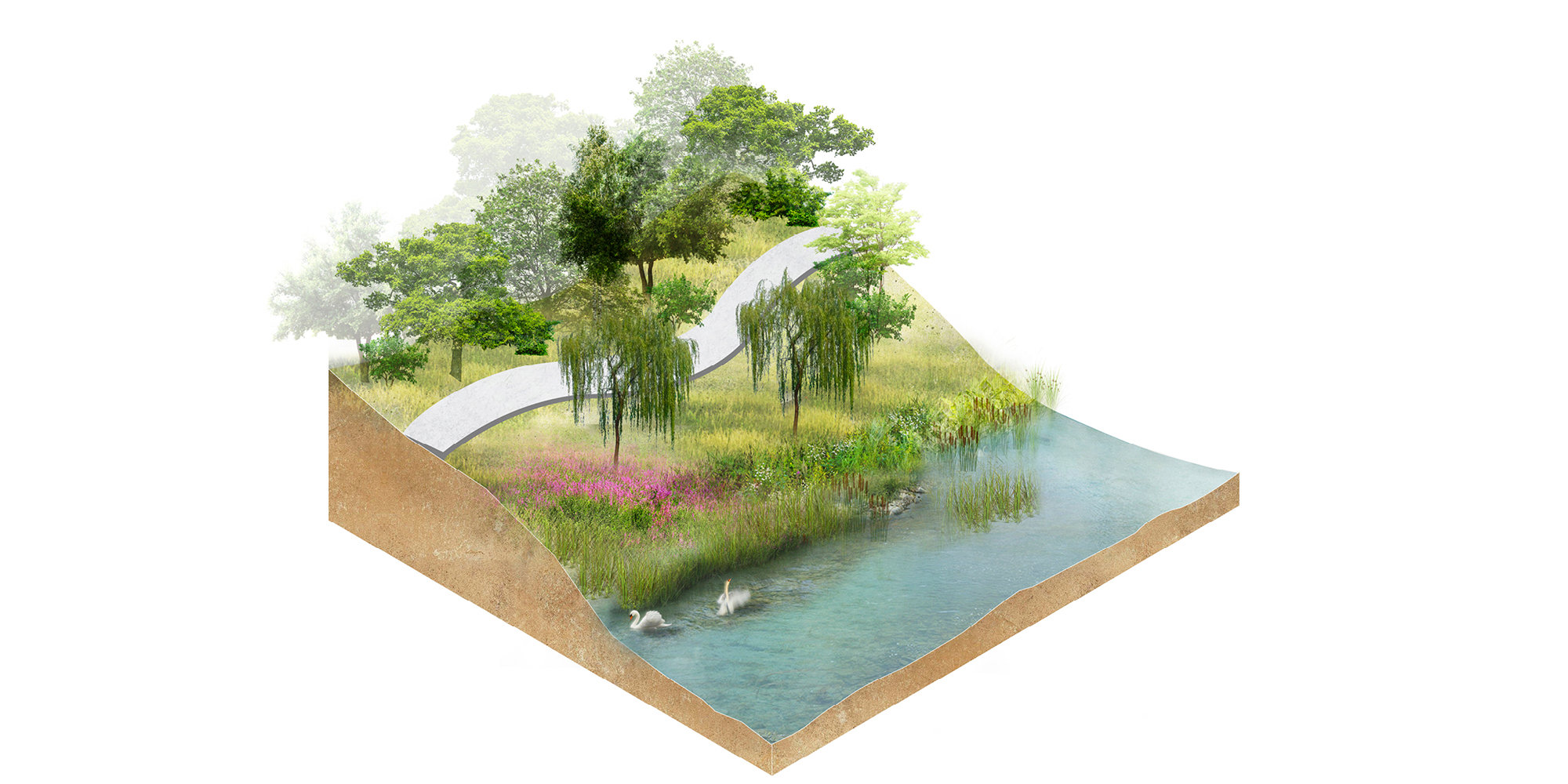

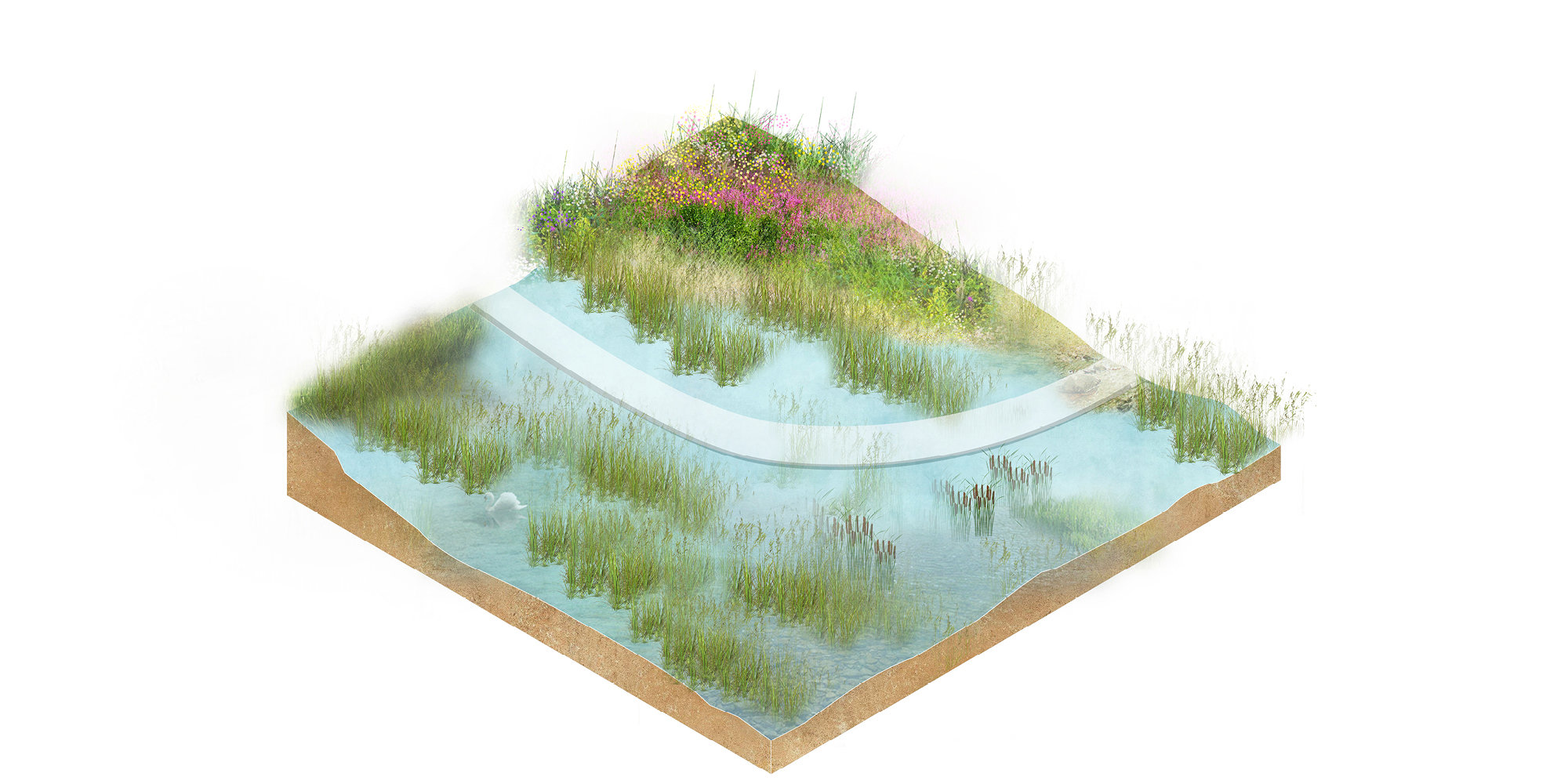

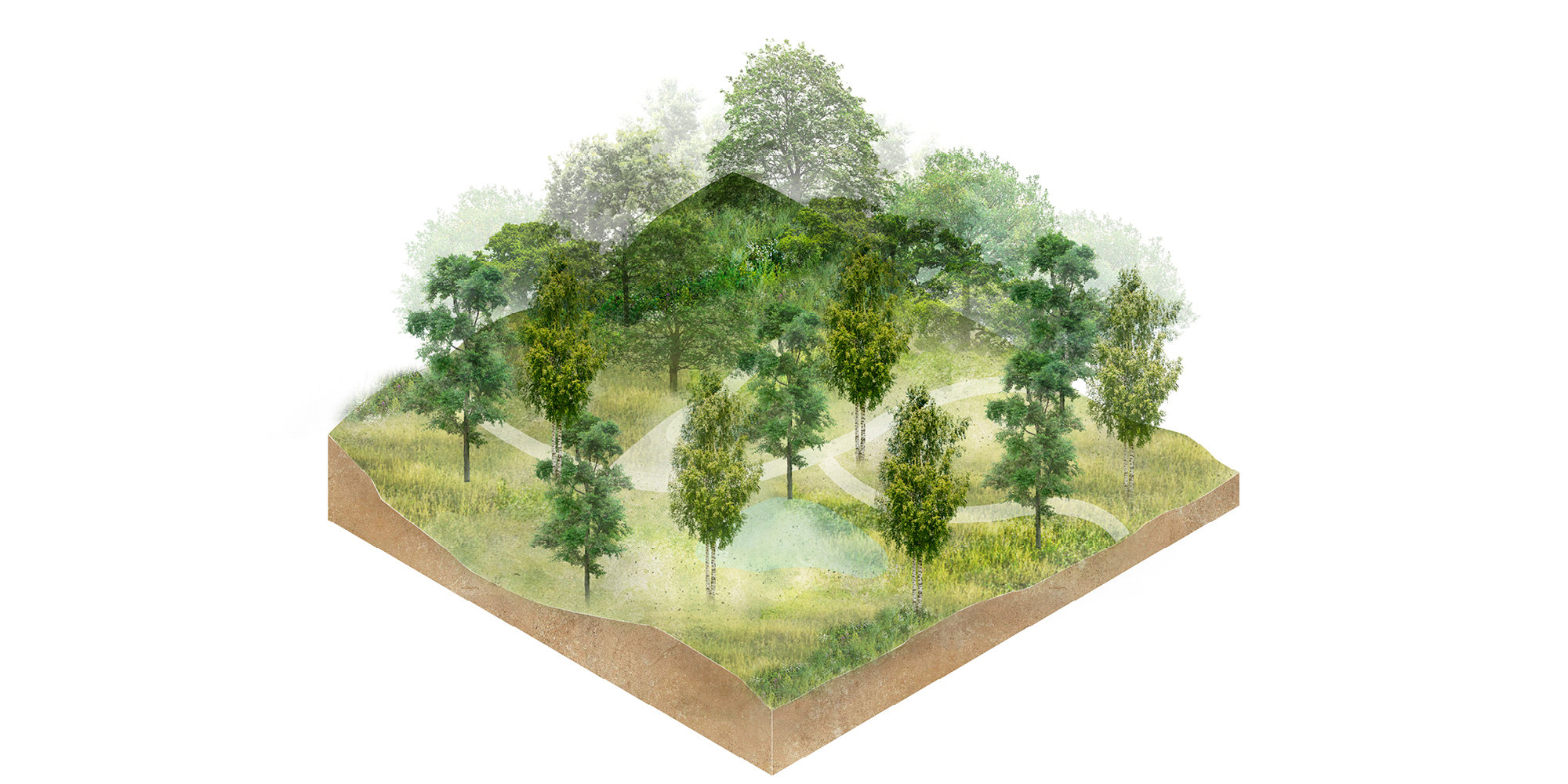

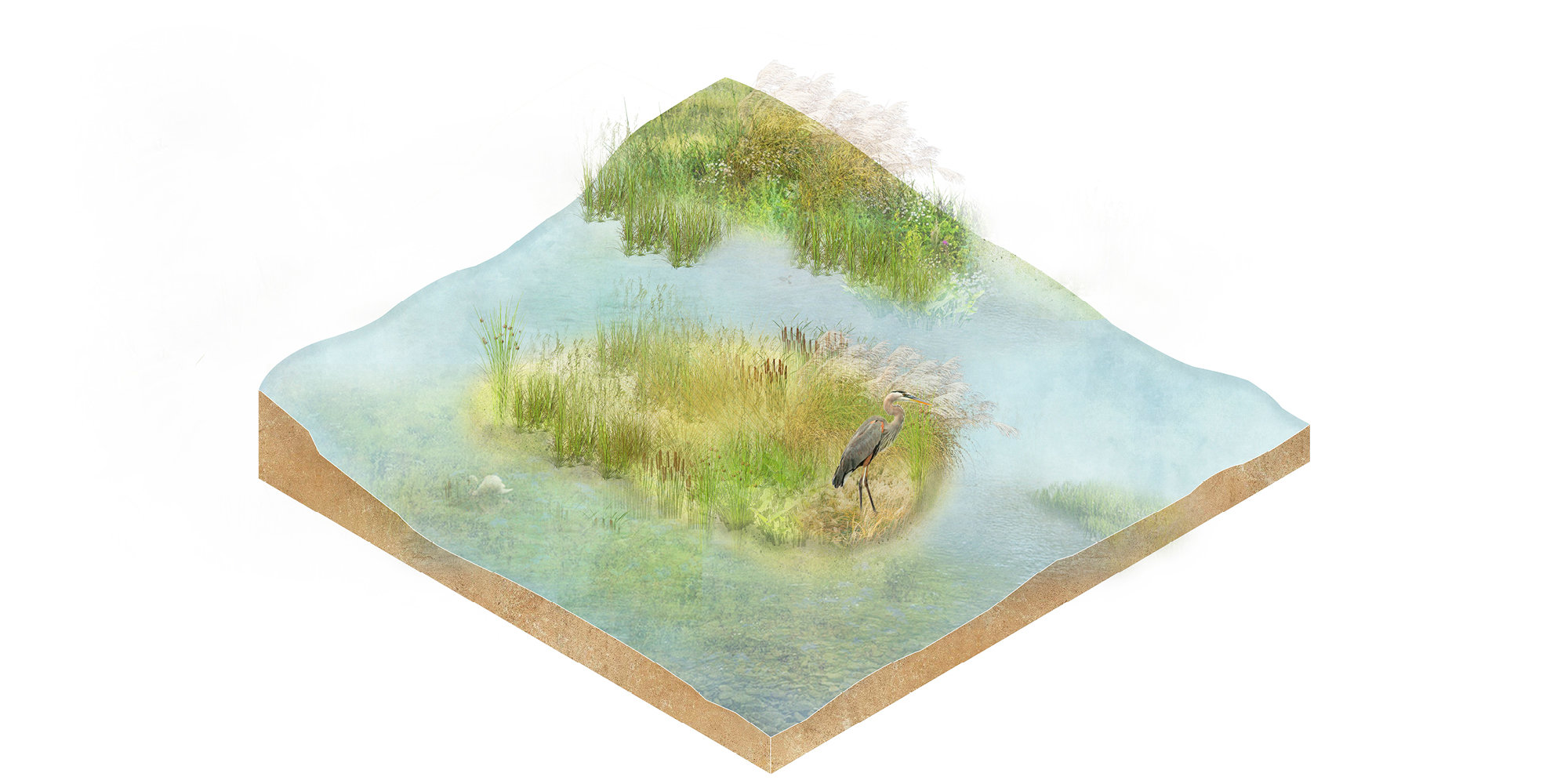

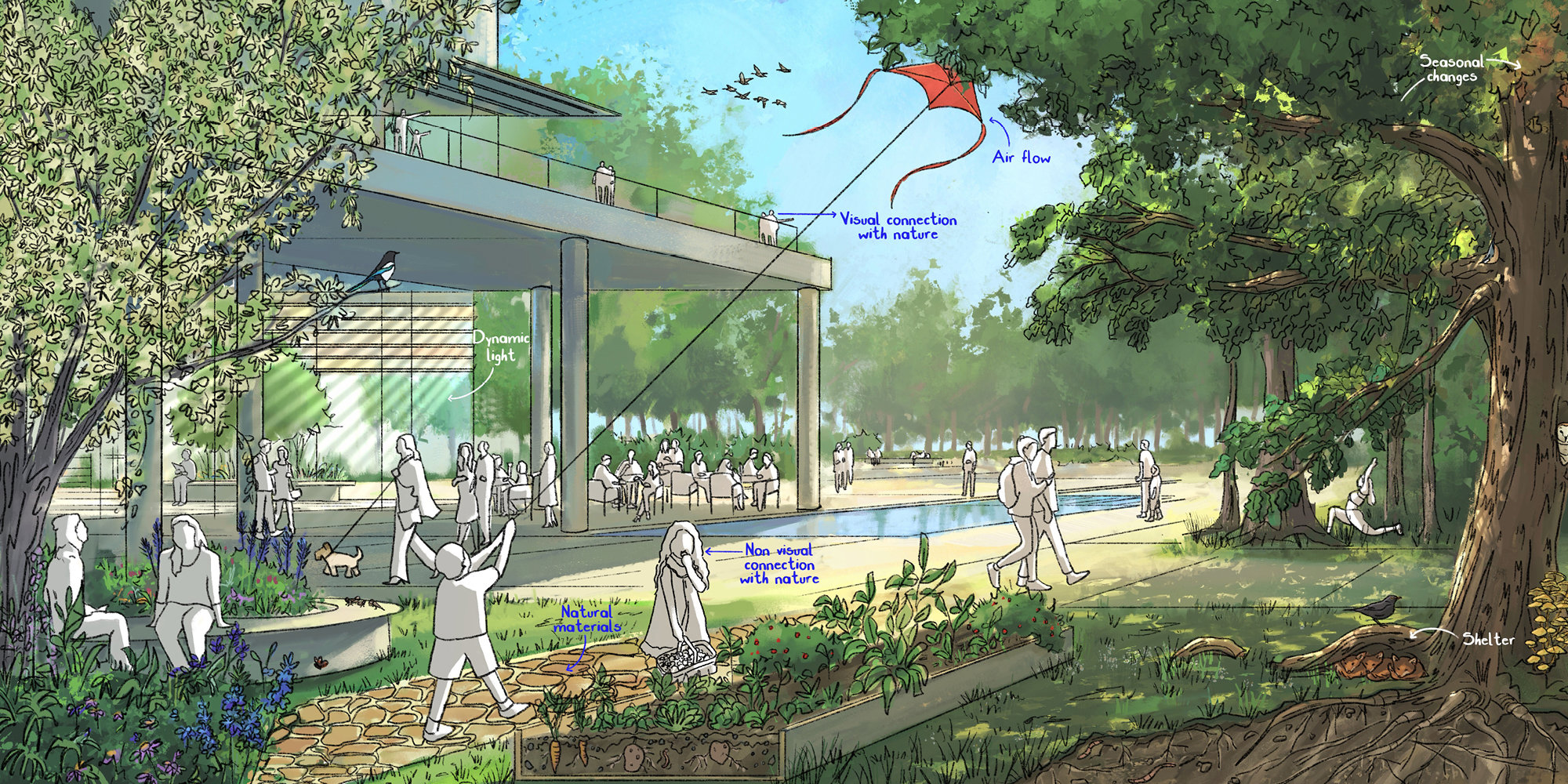

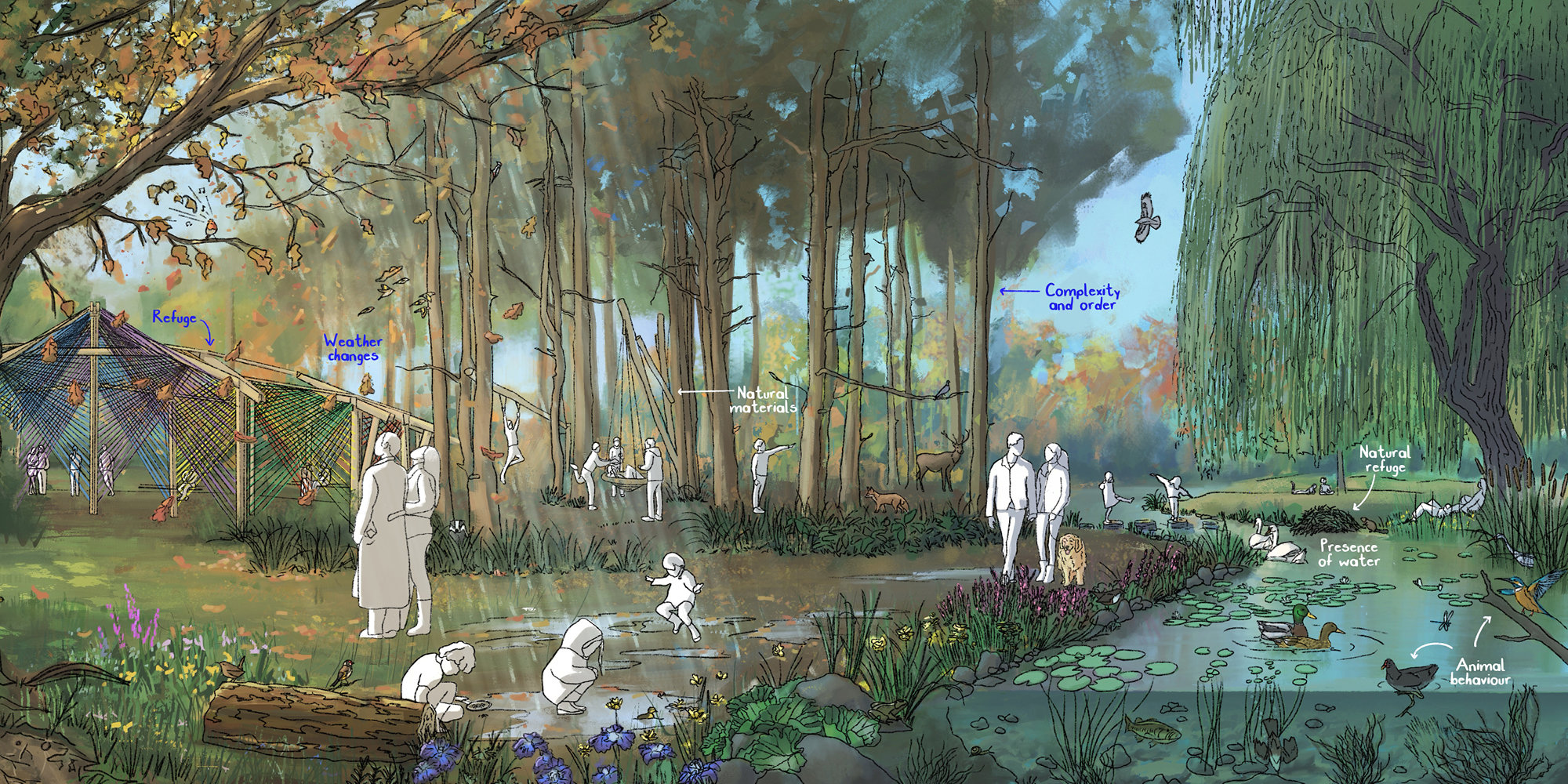

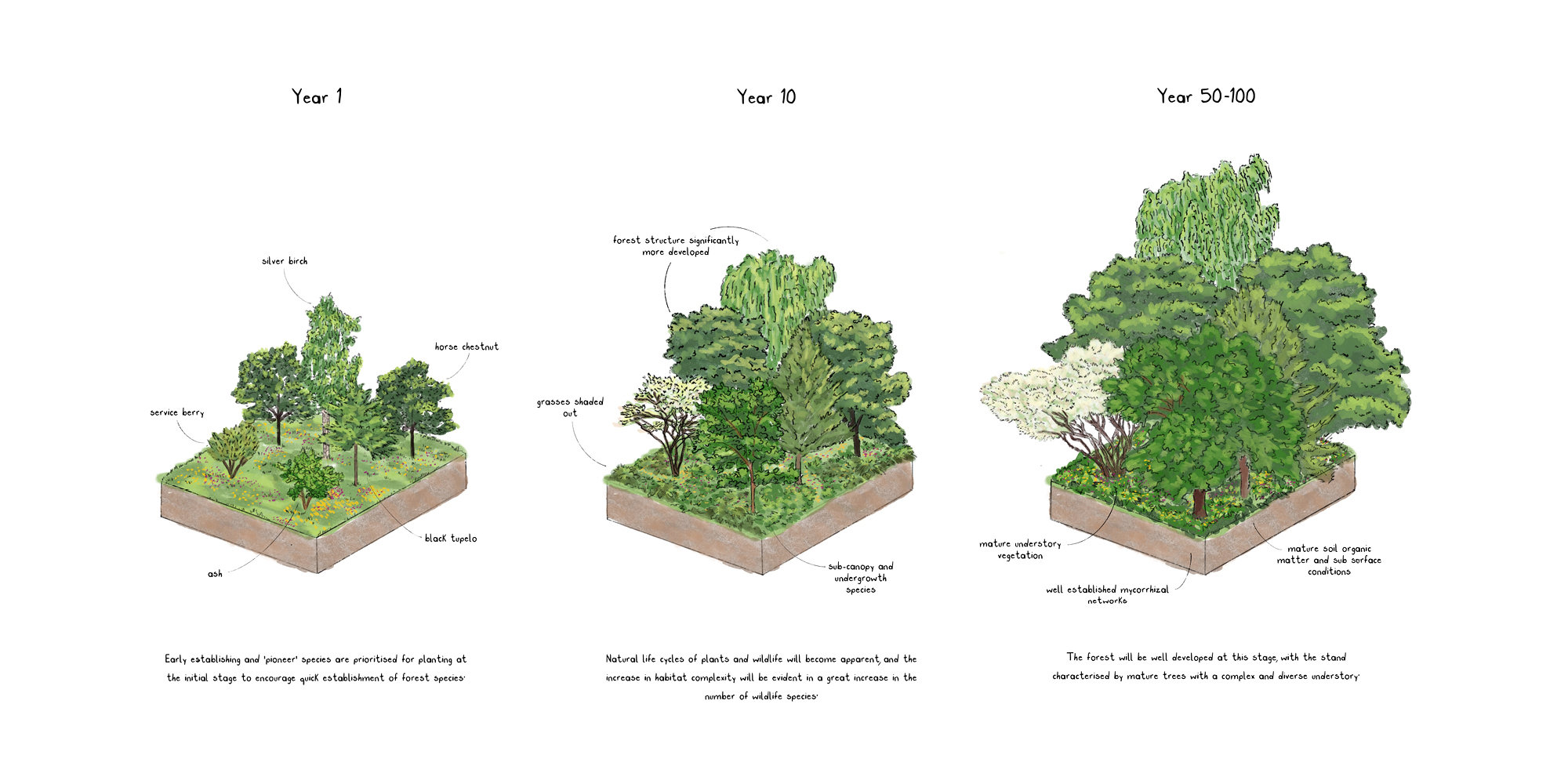

Landscape architecture might be able to answer these questions, given that it is a discipline that has long addressed itself to concerns which are increasingly being brought to the attention of architecture: climate resilience, the responsibility to protect natural habitats and ecological systems, the effects of landscape design on human health and wellbeing, and the short- and long-term environmental impacts of building. A rich and varied field of design, landscape architecture has an essential part to play in the future of our built environment and, by extension, the future of our planet.

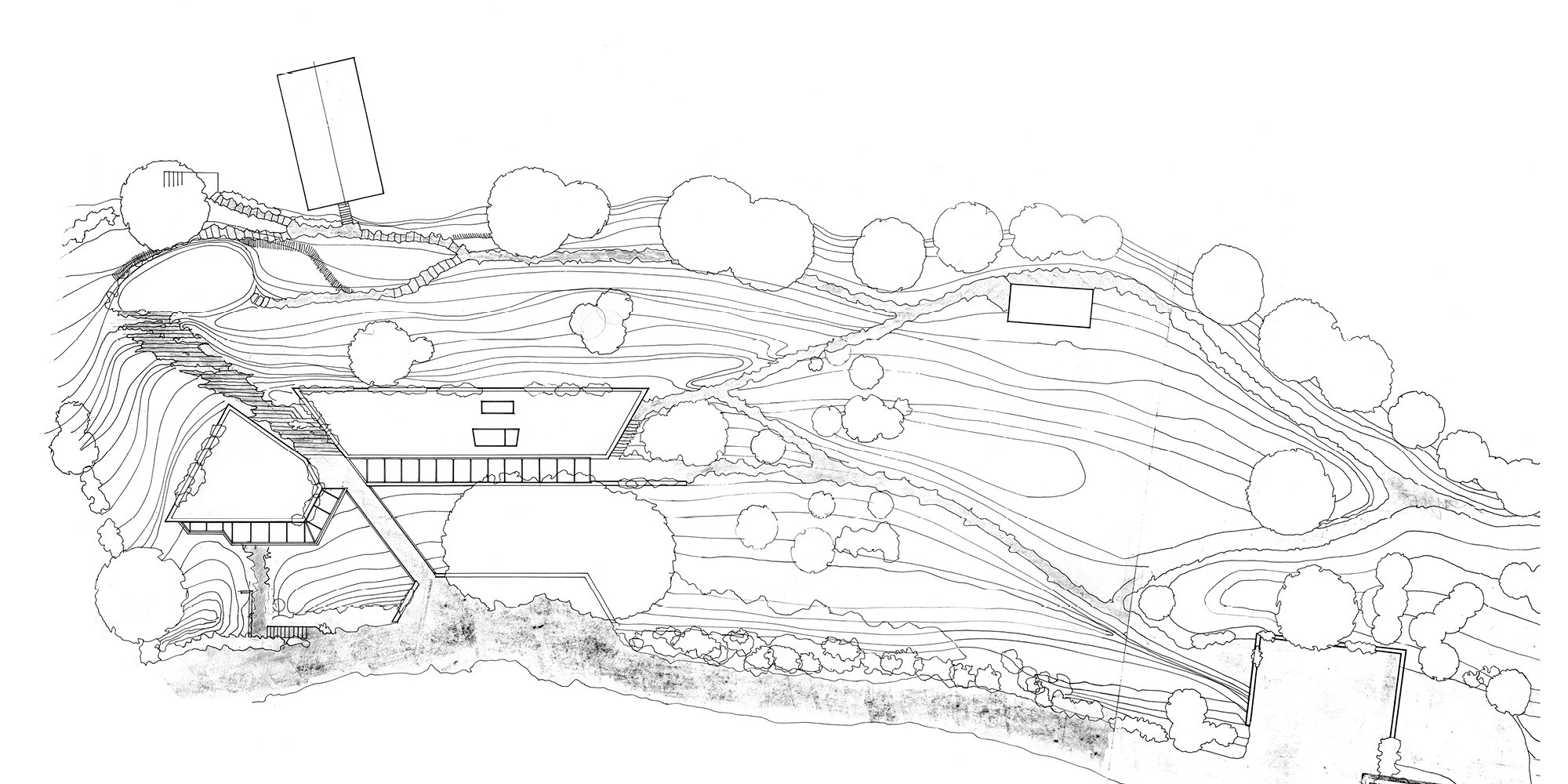

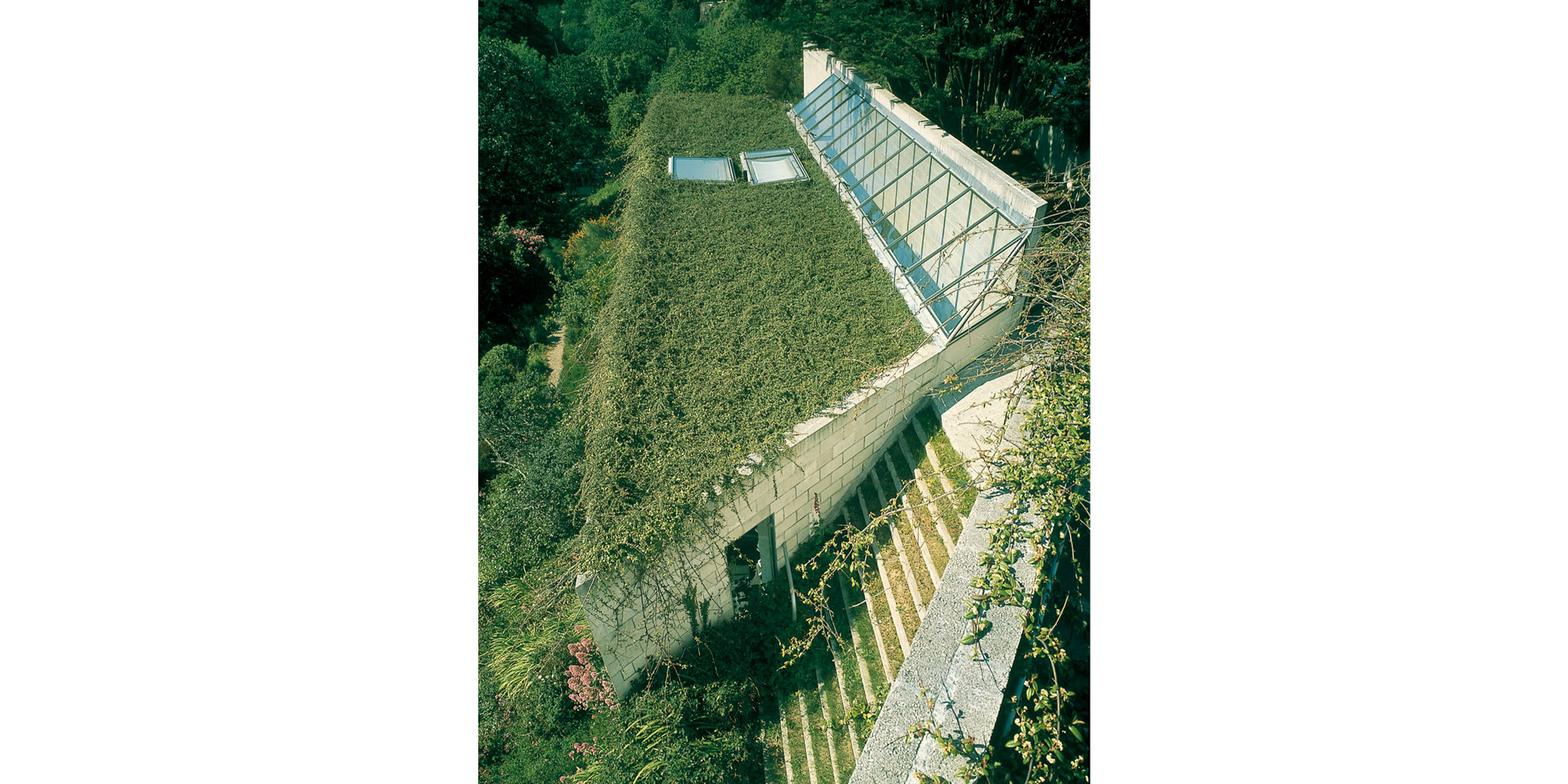

Foster + Partners’ professional landscape team are an essential part of the practice, working alongside architects, urban designers, and environmental engineers throughout the development of the design, implementation, and on-site supervision of construction and planting. The skillsets within this team vary greatly – from rigorous site analysis to ecological expertise, environmental psychology to maintenance planning. Equipped with this wide array, the landscape architects can propose design solutions to make projects more climate-conscious, contextually-aware, adaptable to change, welcoming for many varieties of life and valued by those who use them – in a word: more sustainable. Such outcomes are made possible through the practice’s interdisciplinary ways of working. As Ahmed Abdelsalam, Landscape Architect at Foster + Partners observes:

Architecture and landscape constantly respond to and influence one another. This means that the way that we design must, similarly, be interconnected.

Emerging from the Garden

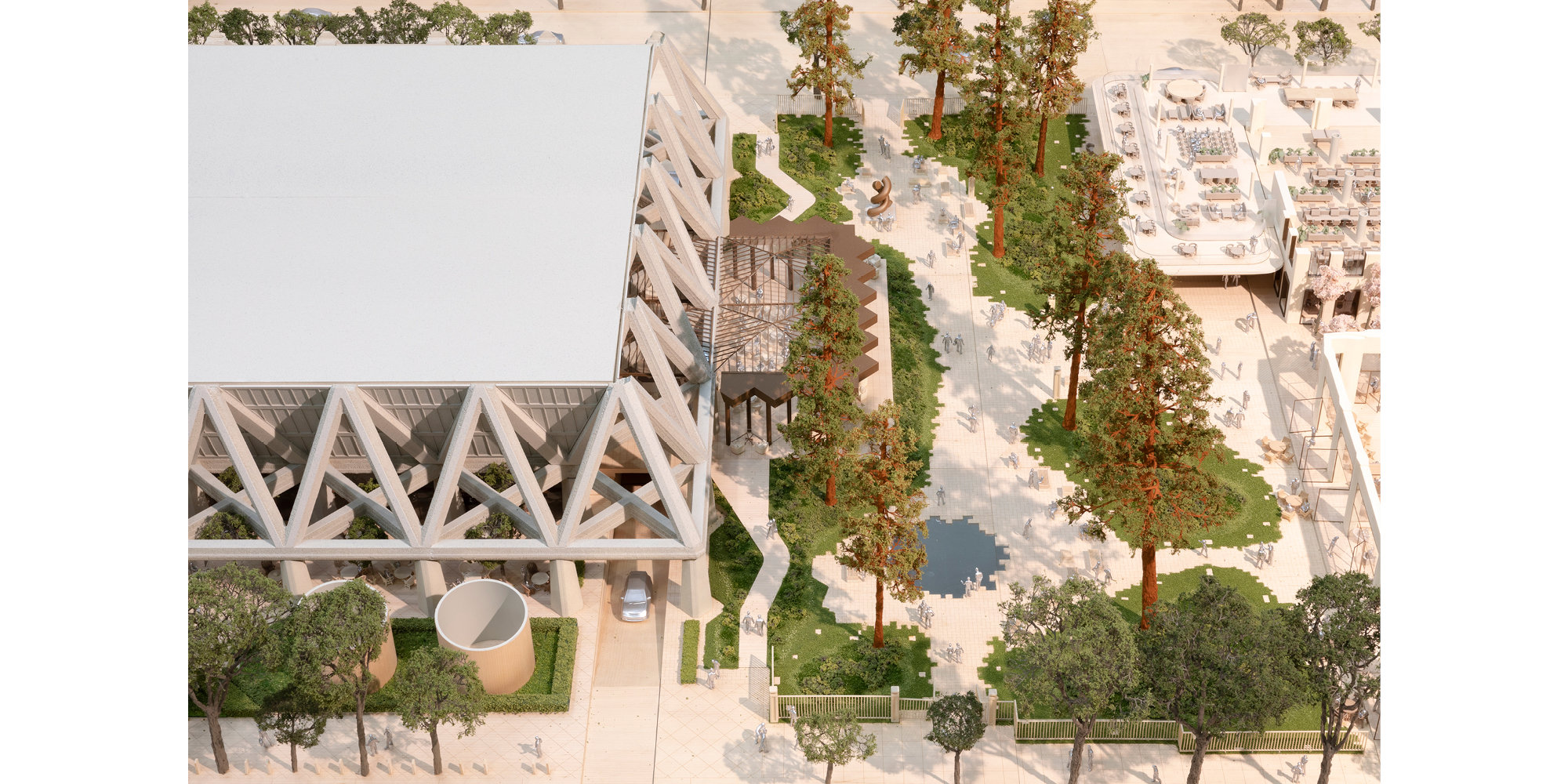

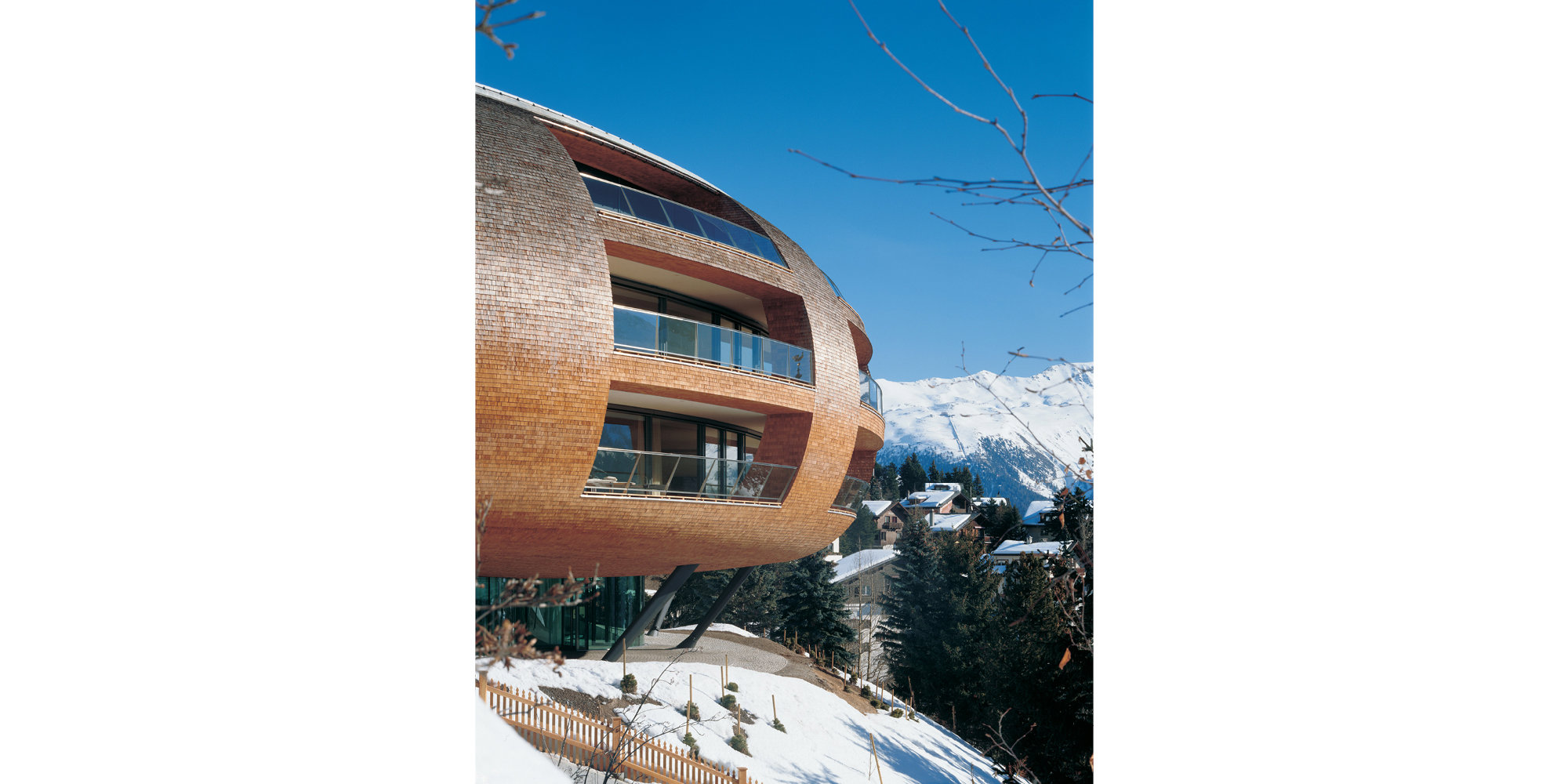

The Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida (2019) is a direct result of this productive relationship between landscape and architecture. Working with the director of Norton, a plant enthusiast and advocate for ecological design, Foster + Partners' masterplan envisaged a major new garden as an integral part of the museum, replacing an outdated parking lot. The redesign of the museum and its gardens had also to include the strict preservation of an eighty-year-old banyan tree and required a design strategy that could refer to ecological expertise. Alongside three arborists, who conducted ground radar scans of the tree’s roots, Foster + Partners’ Landscape Architecture team became an integral part of the project.

The team proposed a design solution rooted in horticultural knowledge. This evolved to a project-wide planting approach that used local, native species that suited Florida’s tropical climate and ecosystems. As the design unfolded, it also became clear that Norton’s garden was not only playing an ecological role but a curatorial one. The rich, textured planting became a stage for the museum’s sculptures and installations. The garden’s shaded walkways and seating helped to bring the museum’s collections to life and formed a series of outdoor rooms. By extending the gallery space beyond the four walls of the museum, encounters between landscape, architecture, and art were celebrated, all within a climate- and context-sensitive design.