From the early piecemeal community stadium to the commercial giants constructed today, the history of football is intertwined with the history of the stadium. Angus Campbell, Deputy Head of Studio, together with Jack Morgan, Venue Specialist Architect, reflect on the architectural and programmatic aspects of stadium design. Considering the practice’s first stadium project – Wembley – and looking ahead to projects such as Old Trafford Stadium District and San Siro, the team consider how a stadium’s redesign can positively impact the wider community, honour the cultural and historical significance of the local team, and celebrate the world’s number one sport.

14th October 2025

The Architecture of Atmosphere: Designing Football Stadiums

Over twenty-five years of designing stadiums, Foster + Partners has amassed experience collaborating with specialists for the redevelopment of Wembley Stadium (the ‘home of football’ and England’s national stadium in London, 2007) and the design of Lusail Stadium (venue for final of the Qatar World Cup in Lusail, 2022). Spurred by these successes, the practice established a venue team of its own to provide internationally renowned in-house expertise to architects, engineers, and urban designers. Working together, these interdisciplinary design teams are already looking ahead to several high-profile stadium projects today, including football stadium plans for Old Trafford in Manchester and San Siro in Milan.

Formed on an interdisciplinary philosophy – which combines skills as various as city and transport planning, lighting and acoustic modelling, and heritage and cultural studies – the practice brings a host of design specialisms into the wider field of play. This approach allows the design team to view the typology with fresh eyes, equipped with, but not trapped by, the singular focus of specialisms. In the same way that a home, museum, school, or even a city centre requires a particular design attention, so too does the stadium. Each brief is a unique opportunity to consider the form in a new context, under different requirements.

Emergence of the game

As football has evolved so too has the design and planning of the stadium. Football, as it is understood today, took shape in the nineteenth century. To begin with, workers from local industries – such as steel factories, shipbuilding depots, or railway construction – created football clubs, where fans (and players) would come from the communities that they served. Soon enough they formed community stadiums with a community base. The football grounds were basic, functional enclosures designed to accommodate a pitch and its spectators. They emerged in a piecemeal fashion, with stands first along one flank and then another, until eventually the space was fully enclosed, thereby restricting spectatorship to ticket holders.

This form of stadium design was then progressed by Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, who completed a home for his beloved Rangers at Ibrox Park in 1899. Inspired by his work on industrial buildings, Leitch’s stadiums were functional and programmatically efficient. After Ibrox Park, Leitch went on to design many stadiums across Britain and Ireland, which several architects in continental Europe used as inspiration. As popularity for the sport grew, so did the capacity and occurrence of stadiums, with many exciting experimentation with stadium design throughout the twentieth century. Influenced by Leitch, architects such as Pier Luigi Nervi and Le Corbusier demonstrated that stadiums could absorb the tenets of modernism in their design, one of the prevailing architectural styles of the time.

The first camera-recorded football match was between Arsenal and Arsenal reserves, BBC 1937. Founded in 1886 by workers at the Woolwich Arsenal armaments factory, the club was initially named Dial Square after a sundial outside their workplace before becoming Royal Arsenal. © Hudson / Stringer

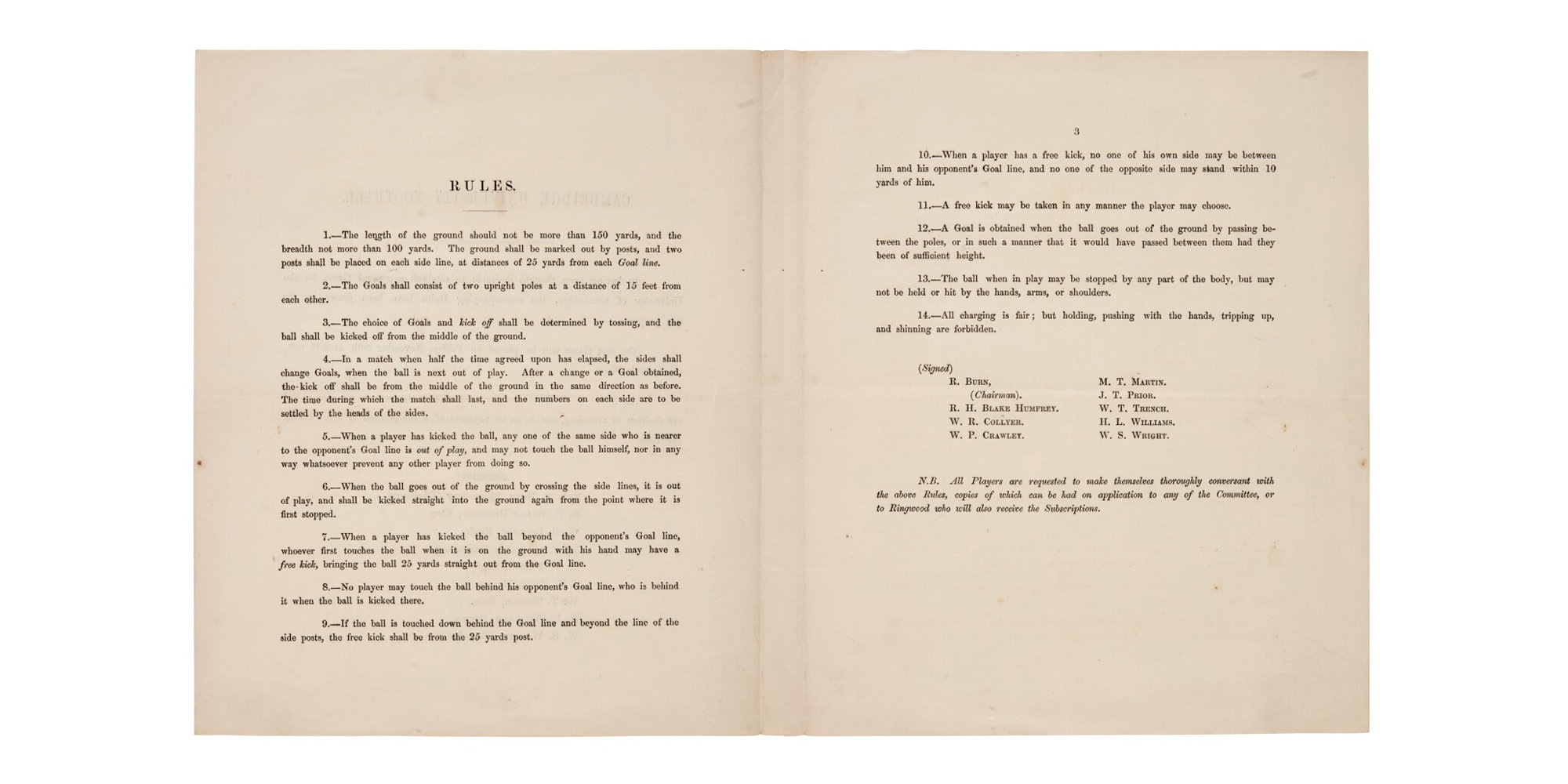

Cambridge University Football Rules, 1863. This leaflet is believed to be the first publication of the rules of football that formed the basis of the first rules of the football association. 'The length of the ground should not be more than 150 yards, and the breadth not more than 100 yards.' Source: Sotheby’s

The rise of broadcasting also had an architectural impact. By the 1950s, clubs had also begun installing floodlights in stadiums; these allowed matches to be played and broadcast in the evenings for the first time, with this coming the birth of the European Cup. The overall impact on the game was monumental. Over 32 million British viewers – equivalent to half the population at the time – watched the 1966 England-Germany World Cup Final at Wembley, with 96,924 fans present in the stadium itself, and 400 million viewers tuning in worldwide.

At the same time, as sociologist Fabio Salomoni reports, the post-war generation in Europe was undergoing a ‘Great Transformation’ where ‘young people were breaking away from the hierarchy of the family, acquiring their own spending power and forming groups that followed the game differently from their fathers.’ With this rise of this younger, larger fanbase led to legislation on crowd safety, came stadium management. In the UK, the landmark Taylor Report on the 1989 Hillsborough disaster resulted in the enforcement of guidelines for a new generation of safer stadiums. Perimeter and lateral fencing were removed, and the stands became all-seated, with many European stadiums following suit.

The state of the modern stadium

Today, football is the world’s number one sport, with 3.5 billion fans estimated worldwide, and 120 million fans attending European top-flight football league matches each year, all connected by a shared love of football.

Despite their appearances at some of the most significant moments in modern history and their location in many towns and cities worldwide, football stadiums have remained on the periphery of architectural discourse and criticism over the past century. There are notable exceptions, of course. Though, too often the football stadium is drowned out in its own noise and reduced to its basic infrastructural and commercial role, a role that is optimised with mechanisms for crowd control and sightlines to the events within.

Burgeoning commercial interests in football stadium design over the second half of the twentieth century have led to various expansions and renovations, but also resulted in many new ‘identikit bowls’ worldwide. Matchday spending and hospitality have fast become the main revenue stream for these stadiums, alongside increased ticket prices that reflect what some call ‘the gentrification of football’ – with lucrative concerts and stadium tours bringing in further income on non-match days. These are generally safer, well-formulated, flexible stadiums, but they often struggle to replicate the atmosphere and sense of community pride fostered by their predecessors. Formed almost exclusively by commercial and regulatory pressures, many of these examples bear no reference to their unique fanbase, local community, club history, or architectural context. (Strip away the colour in the seats, and one would find no indication of what city they were standing in or what fanbase the stadium represents.)

Foster + Partners, an architecture and urban design practice founded in 1967, adopts a design-led approach to stadiums that challenge this relegation. The practice acknowledges the functional requirements of a stadium but also views it as a municipal and cultural project, worthy of sustained design consideration. As countless examples show, architectural and urban design, aligned with a strong business and growth plan, is paramount to the survival of the stadium in its modern form. This is not to forget the core structure of the game and the support of the local community, which should also be integral to any design.

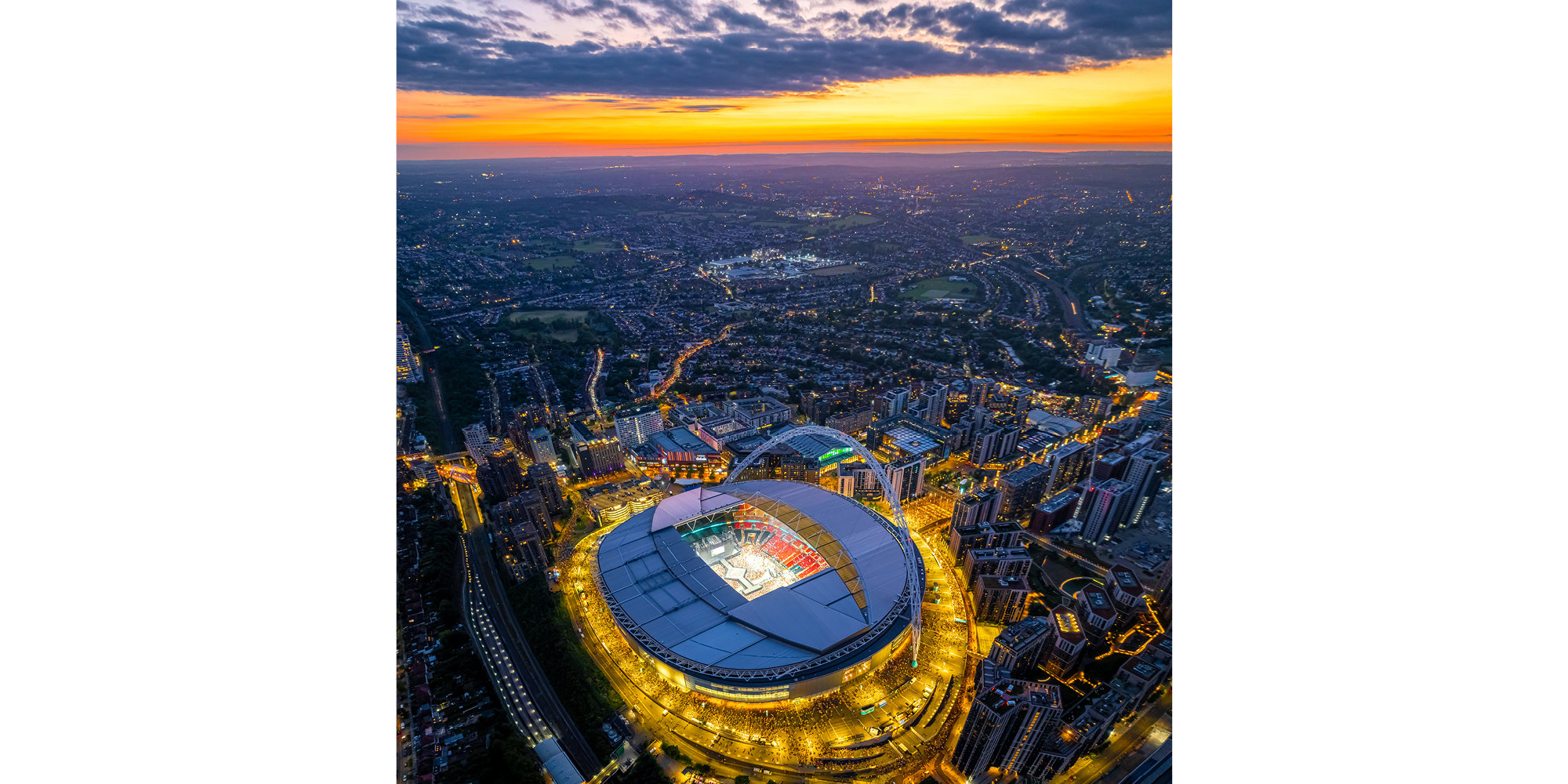

This approach can be seen taking shape in Foster + Partners’ first stadium project (and one of the most high-profile undertakings in stadium design): the redevelopment of Wembley Stadium in 2007.

Designing Wembley Stadium

Perhaps the only Foster + Partners project about which songs are sung by people across the country, Wembley Stadium has become a symbol of national identity and pride – a true ‘cathedral of football’ as Pele once famously remarked.

Seventy-three years after the original Wembley Stadium opened to the public, Foster + Partners was appointed by Brent Council to evaluate the stadium and its surrounding area in 1996. This appointment was a significant moment for English football, demonstrating a desire for an innovative new approach to stadium design.

The Form and Function of Wembley

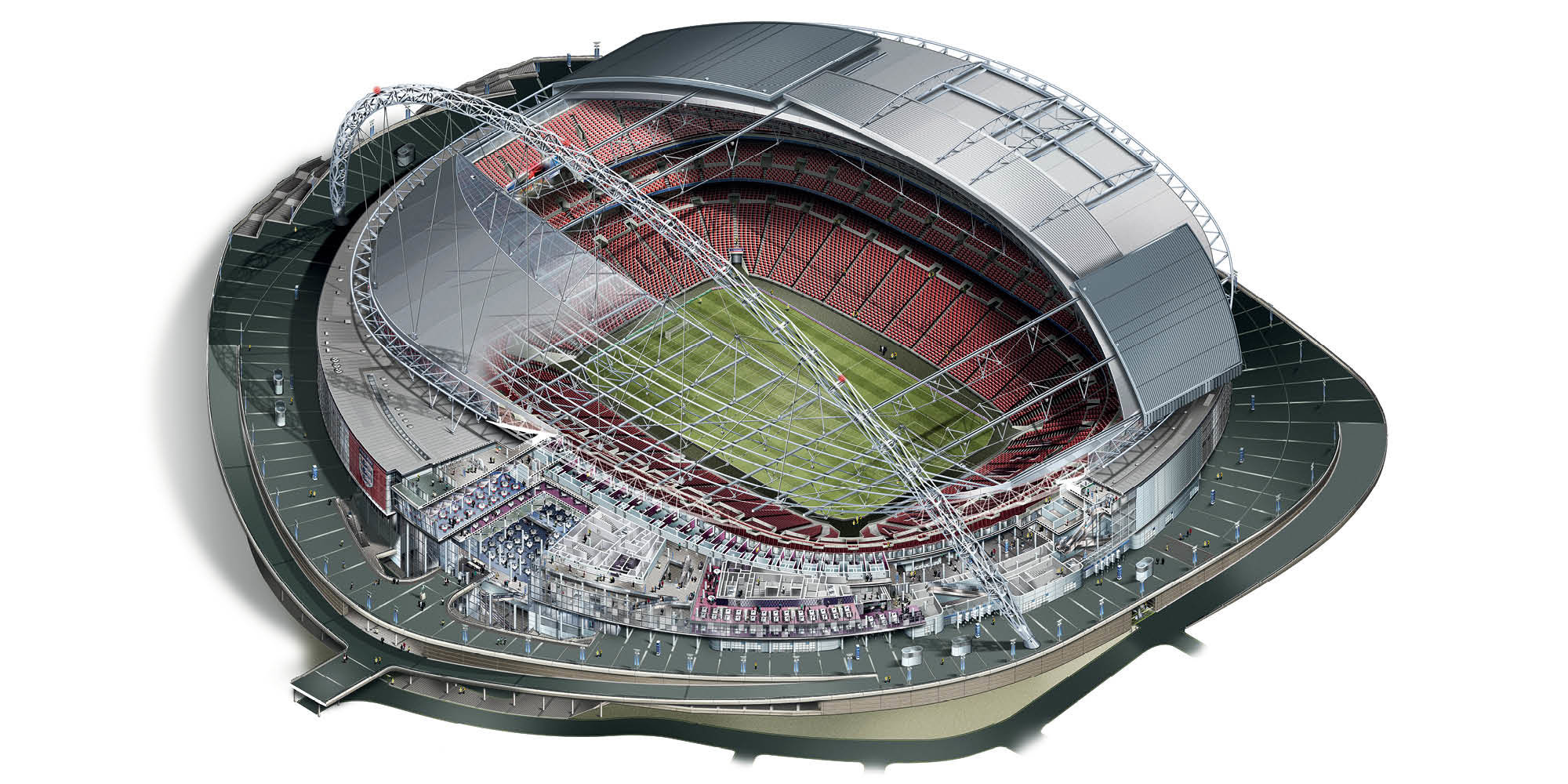

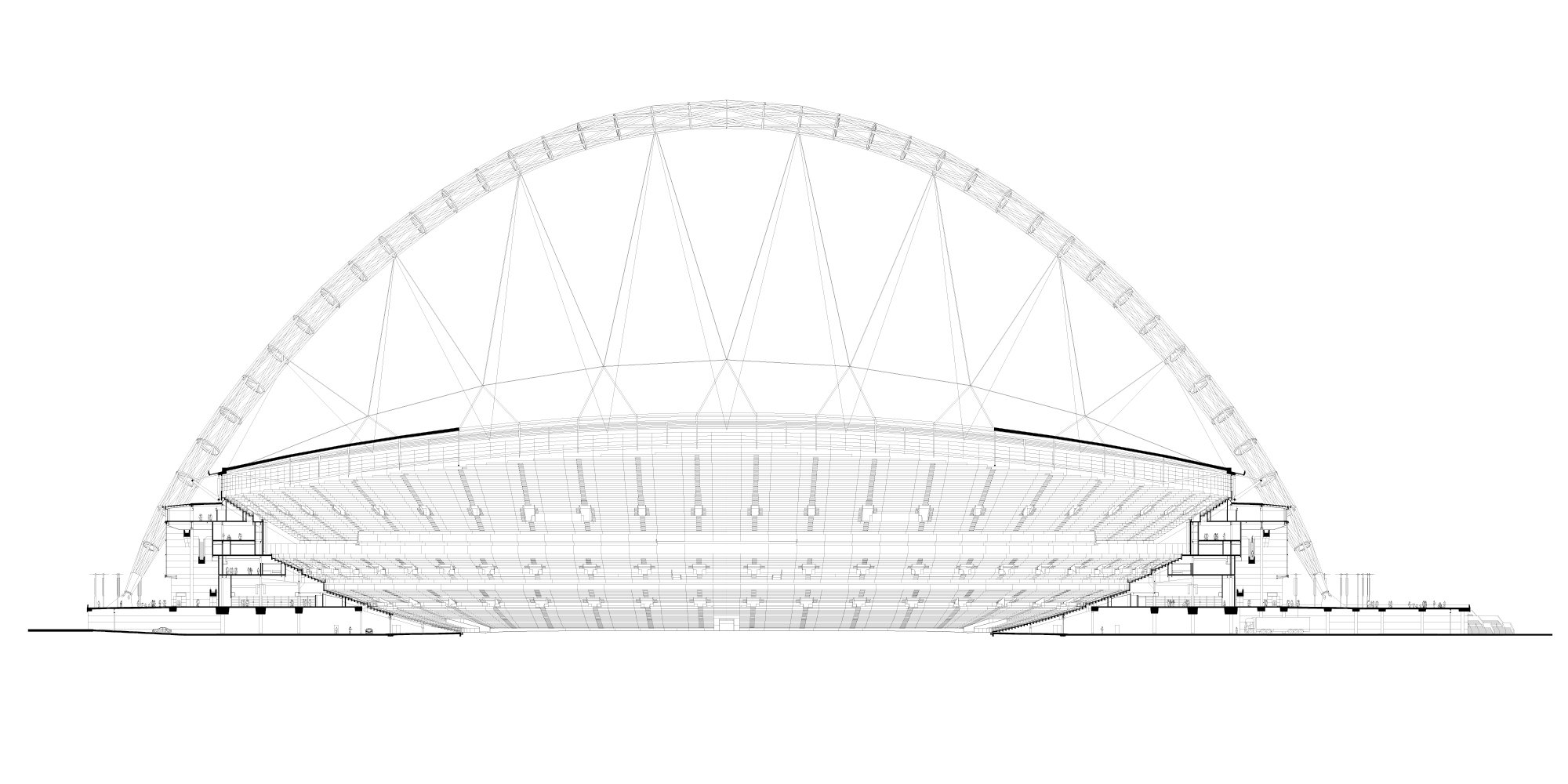

The old Wembley stadium had several unique qualities, which Foster + Partners were mindful of retaining and enhancing. For example, Wembley was known for its ‘hallowed turf’ and one of the greenest pitches in the world, partially due to the original stadium’s unique east-west orientation – and the size of the roof opening – which allowed sunlight to fall directly onto the pitch. According to FIFA’s recommendations, however, pitches in the northern hemisphere should be orientated north-south so that the shadow falls on the halfway line, equalising the impact of sunlight on both teams. In response, the design team felt it was important to retain the east-west orientation, while minimising the amount of shadow cast on the south side of the stadium.

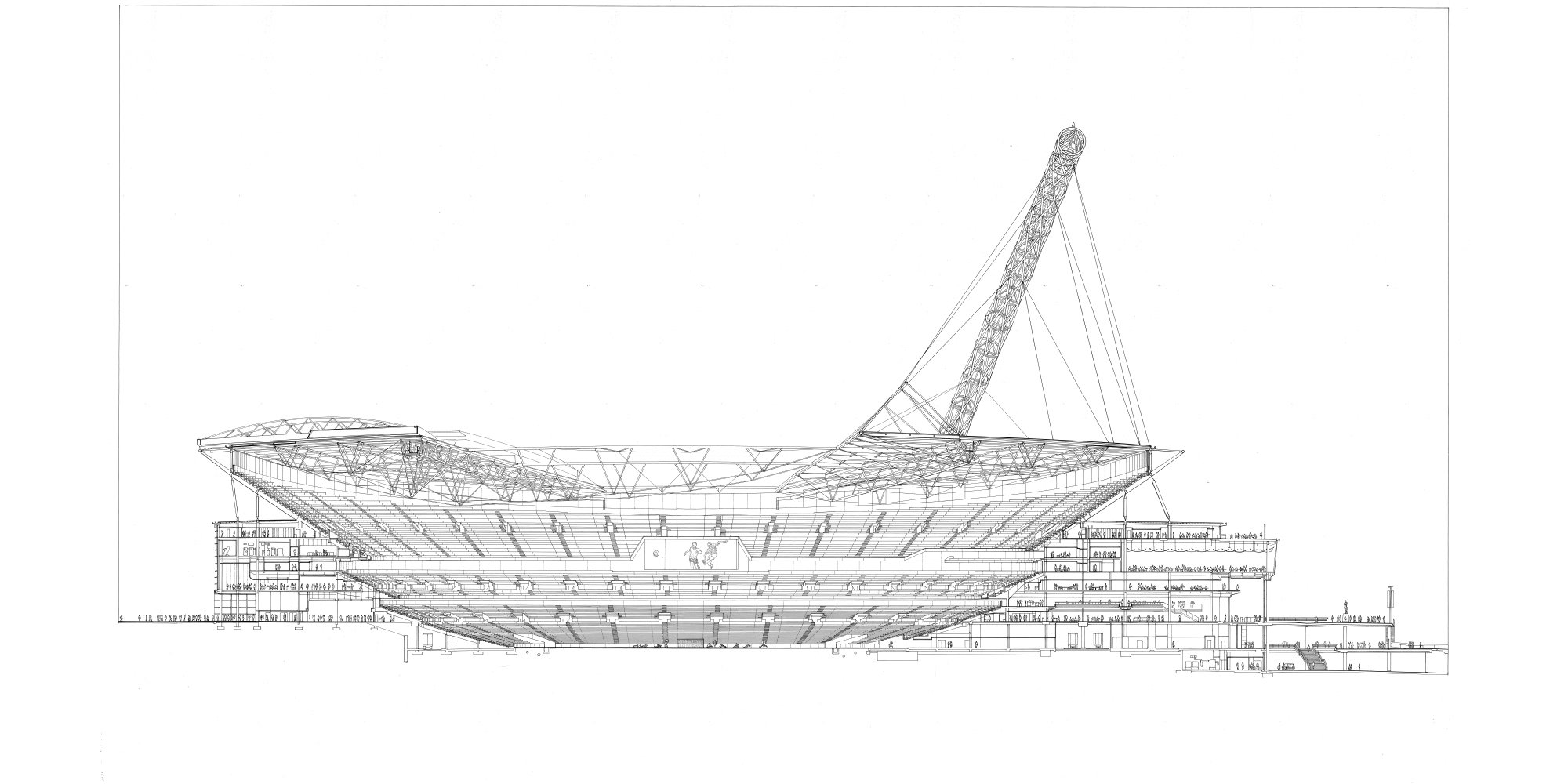

This led the practice to create the world’s longest single-span arched structure, which supports the north side of the stadium. The south, east and west sides of the roof are made from a series of retractable panels, which can protect spectators from the rain and open to maximise the amount of sunlight on the pitch.

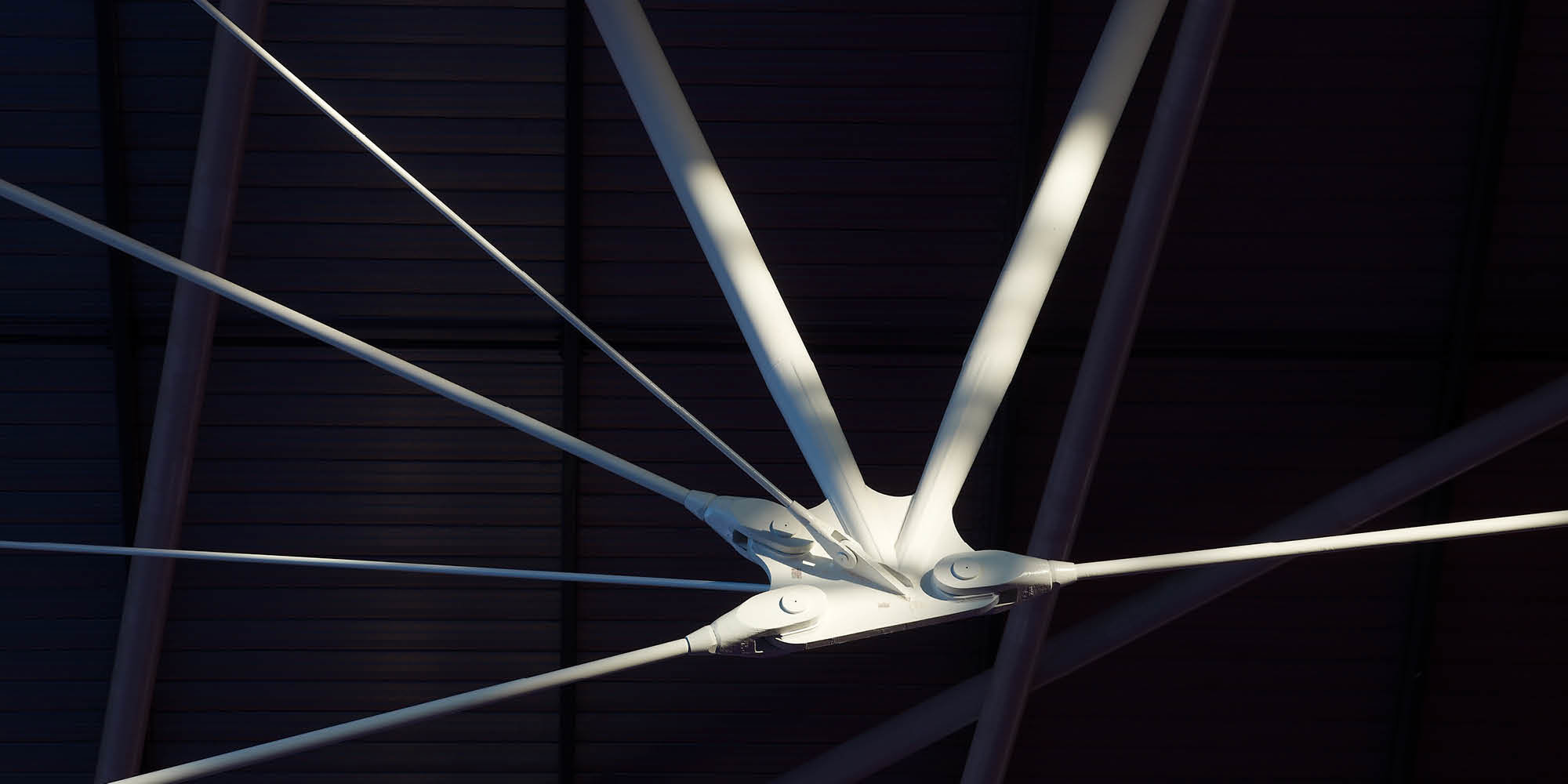

When it came to the construction process, the arch was welded together on the site and then rotated up into position. The 133-metre- (436-foot-) long arch is not only a structural component of the roof support, but a landmark feature that epitomises the stadium itself. Visible from across London, and from cameras within the stadium, the arch’s scale captures the significance of Wembley as a national stadium and provides a visual interface with the wider city.

Detail of the 1,650 tonnes of steel arch that illuminates at night to present a glowing 'tiara' over the London skyline. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The giant German excavator 'Goliath' clears the site; the twin towers remain in the background – the last pieces to go. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The raising of the arch into position. The former ‘twin towers’ of Wembley could not support this roof, and would be dwarfed by the upgraded structure. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The Wembley ‘roar’

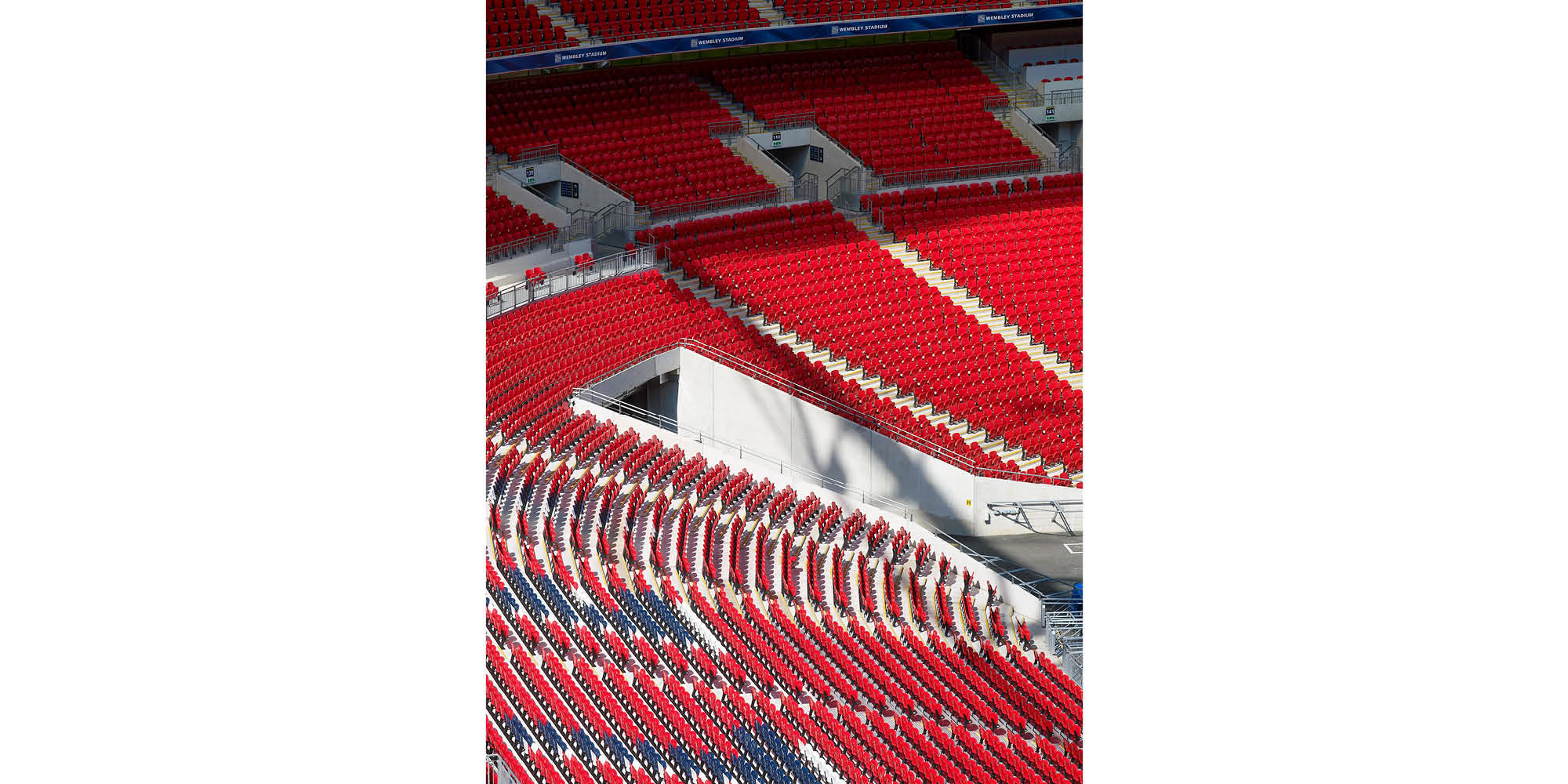

There were also aspects of the original design of Wembley that the team and the Football Association wanted to protect – namely, its atmosphere. The atmosphere of a crowd is not intangible or incidental: it is essential and intrinsic to the function and entertainment of football, and it is a quality that is produced and impacted, in part, by design decisions. Epitomised by the ‘twelfth man’ analogy, crowds aren't mere spectators but active participants in a football game. Research show that players perform better when they can hear their supporting fans. As such, Foster + Partners conducted analysis with the England football team, revealing that most of what players hear comes from the lower tier of the stands. This resulted in a design that offered a large lower tier, with more seats. The old stadium’s athletics track was removed, and the shallow seating bowl, which had distanced football fans from the game, was redrawn. Additionally, the back of this bowl was also connected and sealed to the stands to better reverberate sound, recreating the distinctive ‘Wembley roar’ for which the stadium is famous.

In addition to football, Wembley has always been a destination for all kinds of sports and concerts. It has a place in the national consciousness for everyone, not just football fans. From Bob Geldof’s Live Aid in 1985, which included a set of legendary performers (David Bowie, U2, The Who, Paul McCartney, Sting, Phil Collins, and Queen) to the sold-out arena tours that artists such as Adele and Taylor Swift have brought to the stadium, Wembley has participated in the history of performance as much as sport.

Another important design decision – whether for sport, concerts, or gatherings – was not to split up the stands with hospitality more than necessary. The Royal Box, as well as other hospitality offerings, is made part of the middle layer of the seating bowl and stitched in between the crowd to preserve the overall atmosphere, provide visual continuity, and inspire a sense of community amongst the crowd.

Nearby streets are planned as overflow space to ensure crowd safety, and retail and residential units animate the area year-round. Since the stadium reopened in 2007, in line with the practice’s vision for Wembley, more buildings have been added and the area has become a very successful mixed-use city quarter.

Wembley has a reach far beyond the footprint on which it sits, but it remains, first and foremost, an excellent football stadium occupying an essential place in the hearts of football fans across the country, and capable of generating an incredible atmosphere. As well as delivering a successful programmatic and functional design, Wembley captures many of the concerns of a stadium design today: a distinctive visual identity; a commitment to the fans that fill the stadium, and a robust and thriving urban plan beyond the stadium stands.

Beyond the Stadium: Wembley as Urban Quarter

Alongside the redesign of the stadium itself, Foster + Partners were asked by Brent Council to address access problems with the old Empire Stadium. Part of the edge of the old stadium, for example, could not be accessed by foot due to a train track. A joined-up approach that reintegrated city and transport planning was needed. In response, the practice also developed a masterplan, to enhance the local area and make the stadium more accessible to the public by introducing a concourse that wrapped all the way around the stadium (something that was not possible in the older design). This approach included a reconfiguration to the adjacent Wembley Arena, by flipping its entrance and loading bay, so both the arena and stadium share a processional route from Wembley Park tube station. As a result, an atmosphere of anticipation is shared between the tens of thousands of people who exit the station and approach the two venues.

Technological innovation in stadium design: The Venues Team at Foster + Partners

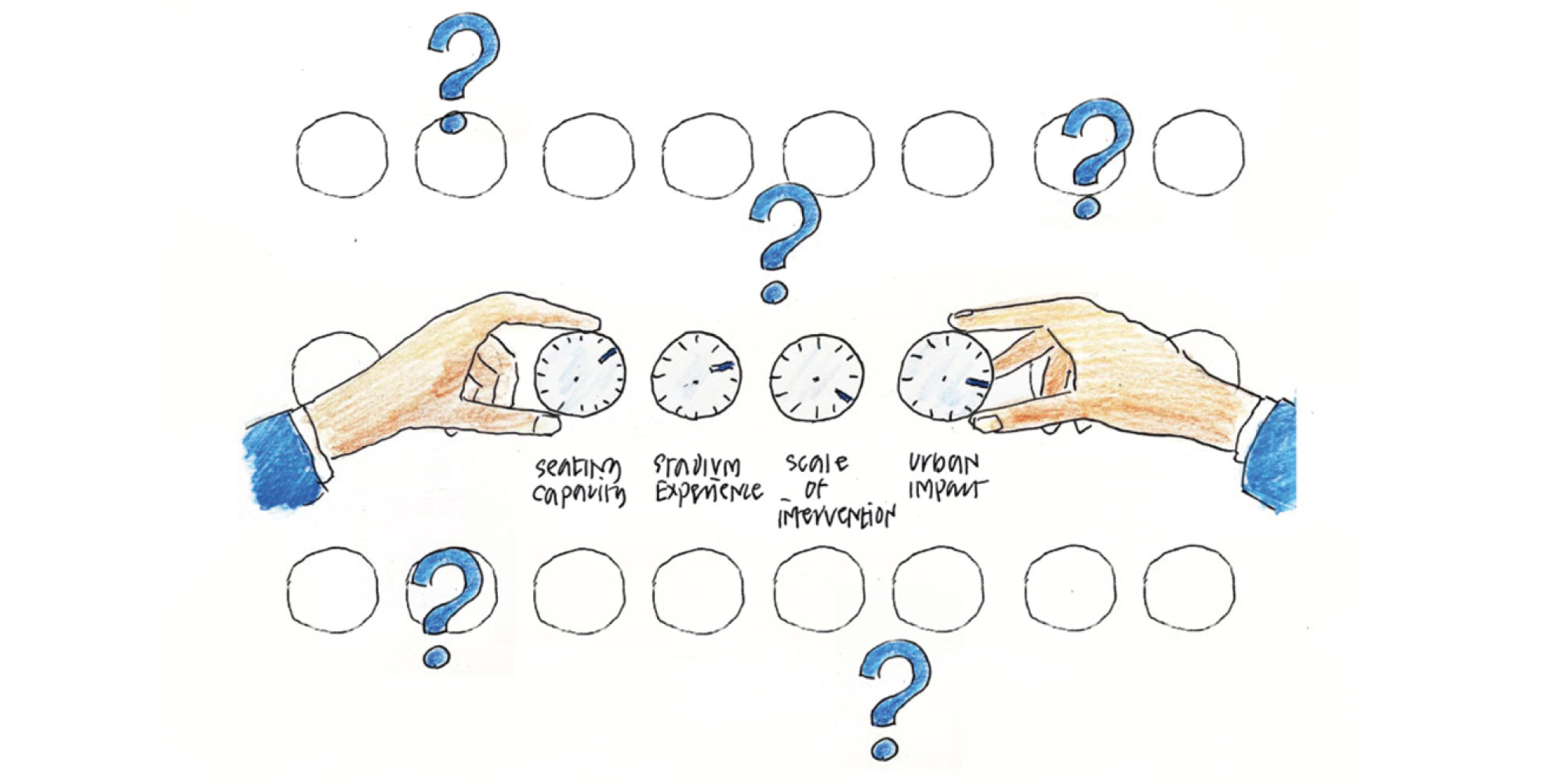

Wembley marked Foster + Partners’ first stadium project. The practice has since submitted the design of Lusail Stadium (venue for final of the Qatar World Cup in Lusail, 2022) as well as several other sports and entertainment venues globally. The recent founding of a specialist, in-house venues team has reflected the practice’s eagerness to explore the stadium typology further, with recently announced projects such as Old Trafford and San Siro. Today, the venues team work with architects, engineers, and urban designers within Foster + Partners to ask: how, in 2025, is the stadium of the future approached?

The Spectacle: Seating bowl, views, concourses

The basic principles of the seating bowl established by the ancient Greeks are still relevant today. Seats are arranged around a pitch or performance area so that every spectator has a clear view over the person in front. Typically, venue designers begin the process by defining what we want the audience to see, known as the ‘focal point.’ In a football stadium, it is vital to ensure everyone can see the entire pitch. Of course, not all views are equal; the view of a goal line is more important than the view of a touchline and the geometry of the tiers may reflect that. Even the extent to which spectators can see one another can affect a crowd’s feeling of unity. A number of other parameters also define the geometry of the bowl, some of which are limited by guidance and codes, and some of which are within the remit and creativity of the designer to play with.

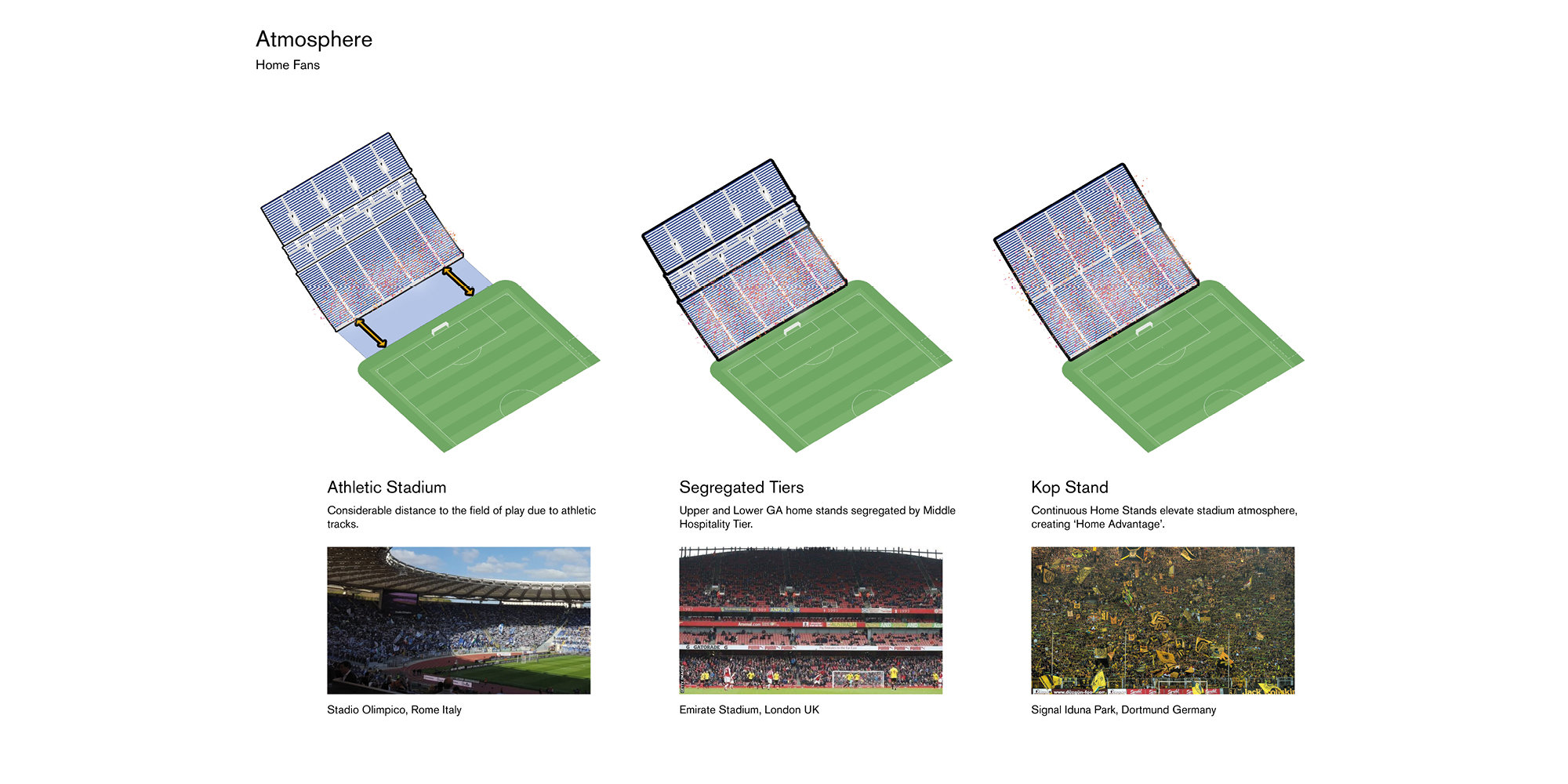

The evolution of stadium home stand and its effect on atmosphere. Early stadiums designs had athletic tracks that distanced fans from the pitch; the introduction of hospitality in the middle tier also separated lower tier and upper tier home fans; today the 'Kop' stand model offers a dedicated uninterrupted stand. © Foster + Partners

Today, computational design is used to ensure mathematical optimisation of the seating bowl, which contributes to improved atmosphere and views. However, this can come at the expense of character and identity, unless the bowl is rigorously, iteratively, designed with the same architectural principles as every other part of the building.

Concourses, once seen as simply a means to an end, delivering spectators from the turnstiles to the terraces, are today understood as a key component in the matchday experience. The best examples allow for an extension of the atmosphere from the terraces to the concourses behind, allowing spectators to mix and share in collective anticipation ahead of the match. As we would when designing any other public building, we want fans to be allowed to explore the entire building, meet up with friends sitting in other areas. We want to create a vertical ecosystem that immerses fans in their club and community.

The interface with the city:

Traditionally, football clubs are located in the heart of their communities, often in constrained urban plots surrounded by residential and industrial buildings. Their urban location and grand scale reflect their importance to metropolitan life. A late-twentieth-century shift towards out-of-town venues surrounded by car parks has thankfully reversed in recent years, as clubs such as Everton and Tottenham have recognised the value of proximity to urban centres and their fanbases. With that comes the challenge of designing stadiums that successfully respond to their context and engage with the community, rather than building impermeable concrete and steel walls that contribute little to the city.

The idea of the stadium or large venue as a tool for urban regeneration has been widely adopted by the industry over the past decade, with examples including Wembley, the O2 Arena in Canada Water, and the Olympic Park in Stratford, London. Gone is the perception by planners that stadiums are an urban nuisance. A well-designed stadium can transform an area for the better, as demonstrated by the clamour by localities around Paris, Milan and many US metropolises to attract professional sports teams with the lure of new stadiums.

One way of blurring the boundary between stadium and city is to broaden the scope of what a stadium can be – a programmatic expansion enabling the stadium to be visited every day of the week. By considering the spaces around the stadium with the same care and attention as the stadium itself, we can enhance and extend the matchday experience. Introducing a walkable precinct, for example, enables and encourages fans to gather before and after the match, building anticipation and fostering connections between supporters. These spaces have the important added bonus of providing for the rest of the population too, making the stadium and its locale a destination for every day of the week.

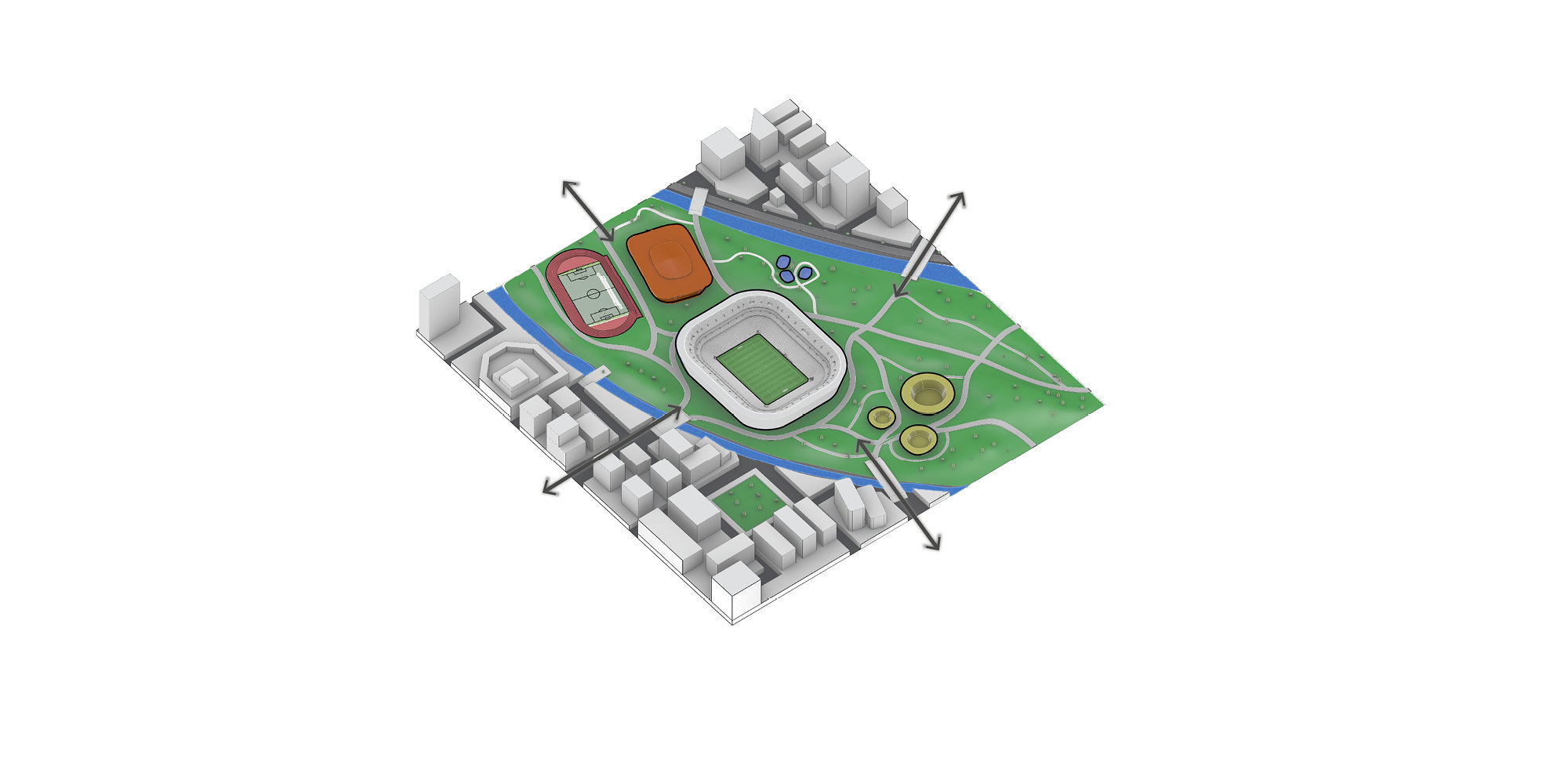

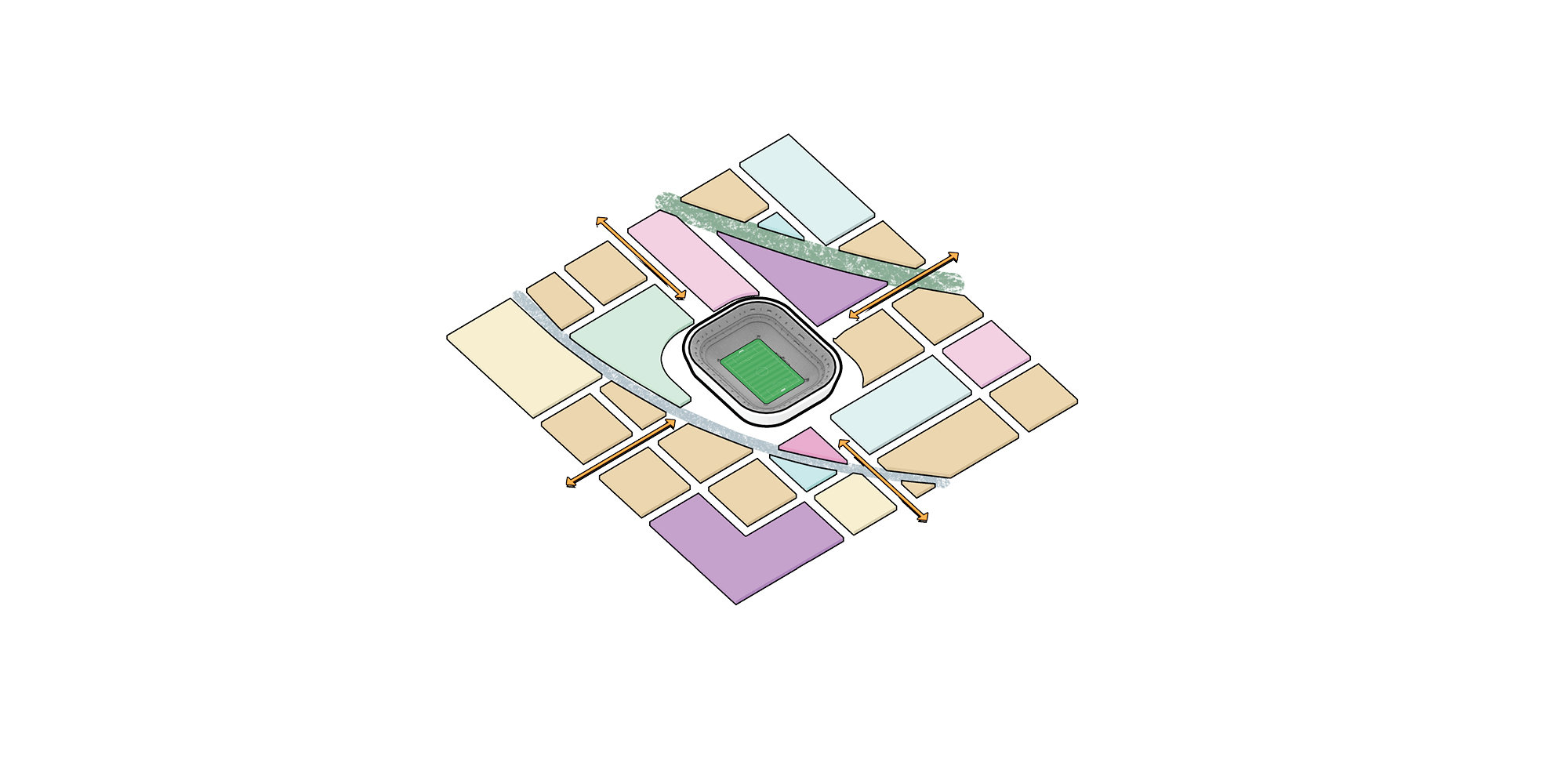

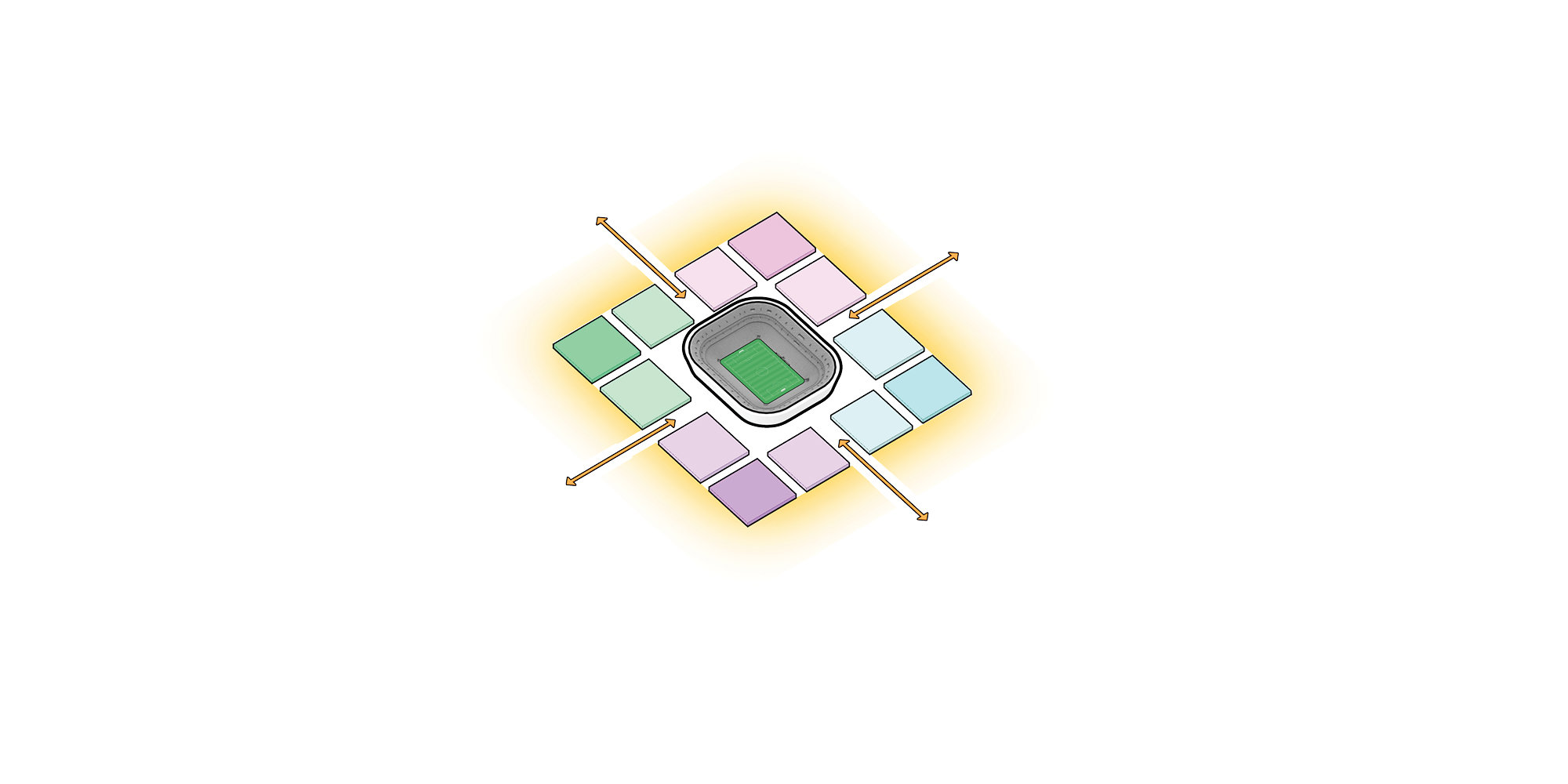

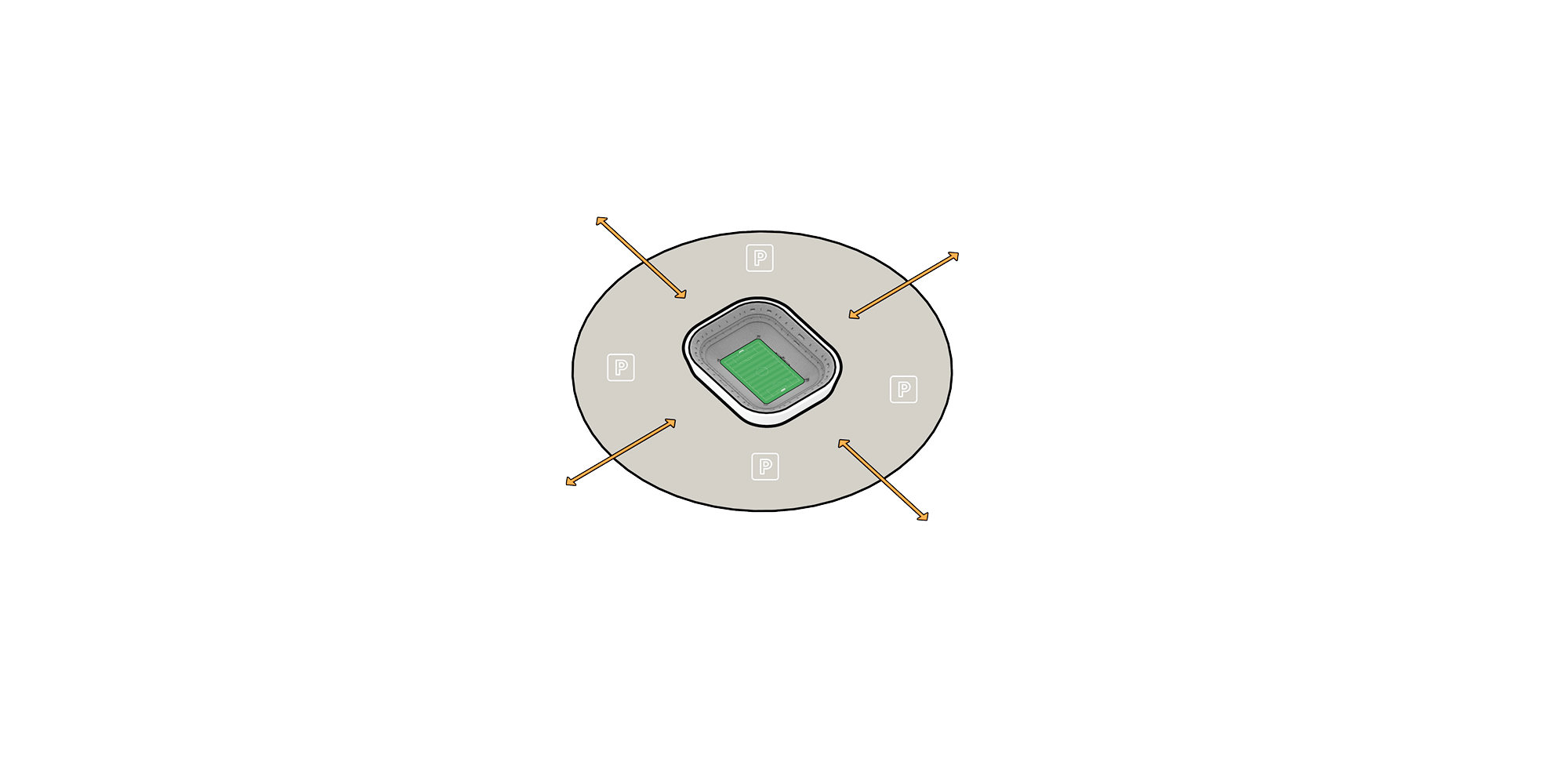

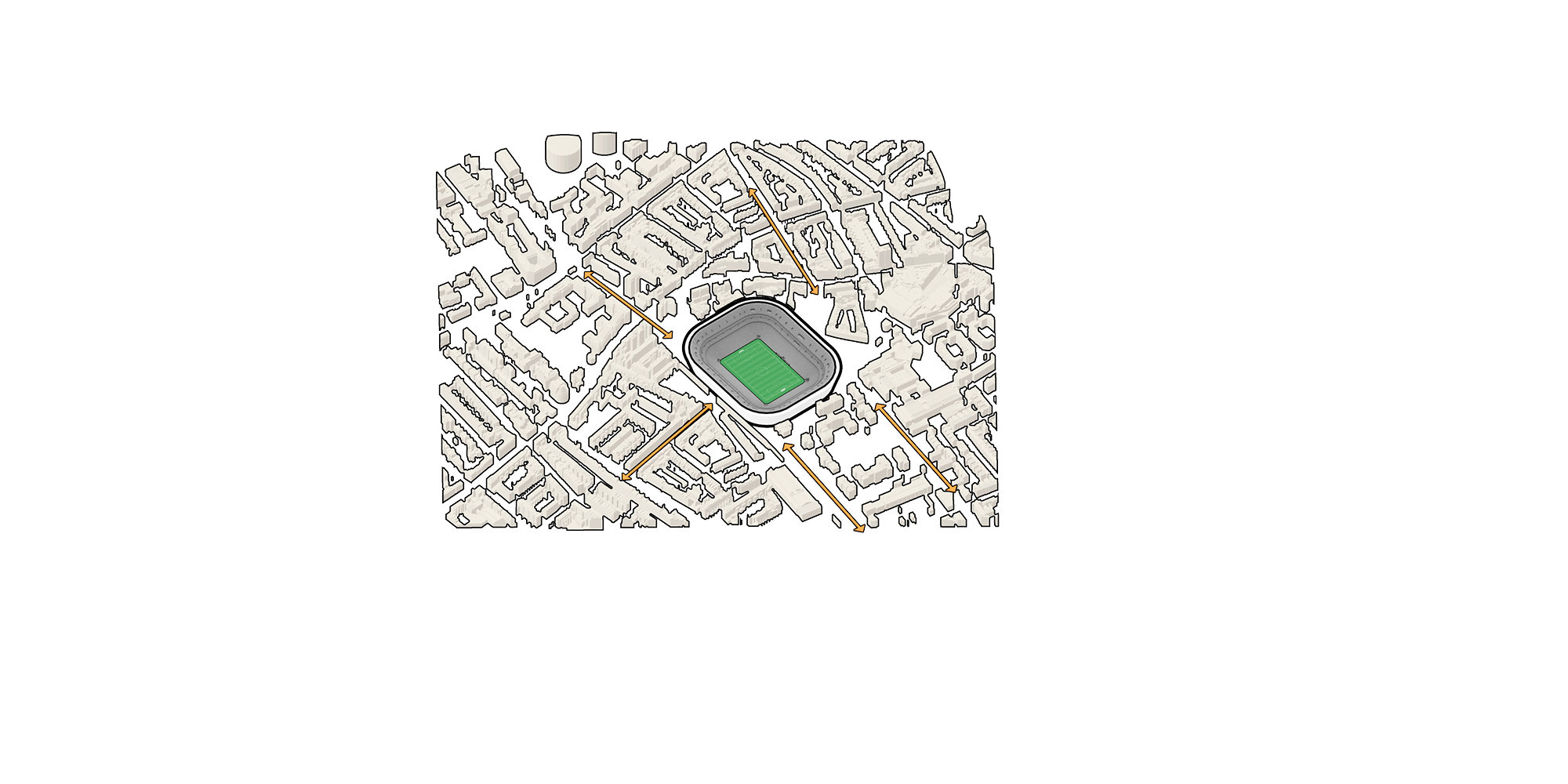

Parkland and community approach, a blend of leisure and entertainment. © Foster + Partners

Entertainment district weaving to the existing site constraints and urban fabric. © Foster + Partners

Site agnostic entertainment district evolve from the availability of vast open space that once dedicated for parking. © Foster + Partners

Vehicular driver approach prevalent in America. Fan driven organic tailgate party evolve from the parking lot. © Foster + Partners

Perfectly imperfect

As architects (increasingly) intervene on existing stadiums, and work for established teams and fanbases, a heritage approach is equally essential as a technologically innovative approach. One reason why stadiums from the pre-war and mid-century era are often cherished is their distinctiveness, in which supporters find familiarity, collective heritage, and pride. Often built without any architectural input – with tin roofs, rusting steelwork, crumbling concrete, cramped seats and wonky floodlights – community stadiums, regardless, often elicit strong emotive responses from their occupiers. In any proposal, the designer’s job involves examining the characteristics that might allow us to replicate or enhance the ‘soul’ of the stadium or stand that is being replaced or updated.

Some factors to maintain and enhance atmosphere are straightforward and consistently applied in virtually every new stadium build: a roof that covers every spectator, steep stands as close as possible to the field, column-free views of the pitch. But most other factors aren’t universal at all, and should be considered based on the location, club, and fan base for each project.

Looking Ahead: Old Trafford and San Siro

These considerations have found their way into two ongoing, high-profile stadium projects that Foster + Partners are currently attached to: Old Trafford in Manchester, UK, and San Siro in Milan, Italy.

In September 2024, Foster + Partners was appointed by the world’s most famous football club, Manchester United, to develop a masterplan for the Old Trafford Stadium District. The focus is to design a world-class football destination and home for Manchester United fans, coupled with a wider masterplan comprising mixed-use developments, which would benefit the local community, attract new residents, increase job provision, and make it a vibrant destination for visitors from Manchester, the UK and all around the world.

Foster + Partners has worked with Manchester United to produce some illustrative concepts for the new landmark stadium, which would sit at the heart of this ambitious masterplan, and act as a catalyst for regeneration. This will provide the basis for more detailed feasibility, consultation, design and planning work as the project enters a new phase.

A year later, in October 2025, AC Milan and FC Internazionale Milano announced that they have signed an agreement with Foster + Partners and MANICA. Following the recent resolution of the sale of the stadium, Grande Funzione Urbana San Siro has been approved by the Milan City Council, meaning that the two firms would be responsible for designing the new Milan stadium.

The new venue, part of an urban regeneration project covering approximately 281,000 square metres (3.02 million square feet) and designed for the benefit of the community through innovation and sustainability, will have a capacity of 71,500 seats and will offer an unparalleled atmosphere. It will feature two large tiers with an incline designed to ensure optimal visibility from every section. It will also meet the highest accessibility standards, providing dedicated experiences for all fans and offering sections with affordable pricing.

Stadium as architecture

The sports stadium has always been a place of solidarity, spectacle and synchrony, but what makes a football stadium particularly unique is its ability to reach beyond its outer stands and connect with the towns and cities – the communities of fans – that support it. Few buildings stir as much excitement and adrenaline as a football stadium, nor as large a crowd.

Football fans confer on the stadium a sense of place and belonging, whether on match or non-match days. How can the stadium reflect this back to the community? A team’s rich history, local traditions, even the songs that are sung on the terraces, should provide ample inspiration for architects, not to mention the surrounding area and its history. The challenge lies in delicately balancing the diverse demands made upon modern stadiums. Guidance and regulations can be challenged, as we have seen with the introduction of safe standing, and there is no shortage of room to innovate. It is possible to create incredible venues that represent the emotional significance placed upon them by fans, as well as the ambitions and investments of their owners. Above all, football clubs deserve a home that recognises and enhances their unique identity. Foster + Partners has developed in the past twenty-five years an approach to stadiums design that goes beyond conventional venue planning, to a more joined-up, urban and community-facing understanding of the football stadium: each one a home to the sport of the world.

Author

Angus Campbell and Jack Morgan

Author Bio

Jack Morgan joined Foster + Partners to support the growth of a new team inside the company, established by Angus Campbell. Together with the rest of the team, Angus and Jack are involved in stadium, arena and theatre projects across the practice, as well as training grounds and sports complexes.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George