Neuroarchitecture is a field that emerges at the intersection of neuroscience, technology, and architectural design. Vittoria Falchini, Workplace Consultant at Foster + Partners – who specialises in neuroarchitectural psychology – explains the frameworks it can provide, the observations it can make, and how neuroarchitecture can steer us towards more considerate design.

11th October 2023

Brain, Body, Building: Neuroarchitecture and Design

When designing physical spaces, we are also designing or implicitly specifying distinct experiences, emotions and mental states. In fact, as architects, we are operating in the human brain and nervous system as much as in the world of matter and physical construction.

– Juhani Pallasmaa, The Architecture of Empathy

The emerging and interdisciplinary field of neuroarchitecture – the discipline of neuroscience applied to architecture and the built environment – seeks to explain how our external environments influence our brain and behaviour. Operating within the Workplace Consultancy team at Foster + Partners, I work as a neuroarchitectural psychologist, specialising in this new area of research. In this capacity I help bring neuroarchitecture into contact with the practice’s design process. Utilising neuroscientific research methods allows us to record how we perceive space, as well as the cognitive and behavioural consequences of architectural and spatial designs. In doing so, we can begin to explain the reasoning of our physiological and emotional responses to different environments. This article seeks to elucidate how neuroarchitecture strives to meld these understandings with architectural implementation.

Neuroaesthetics: How we experience art

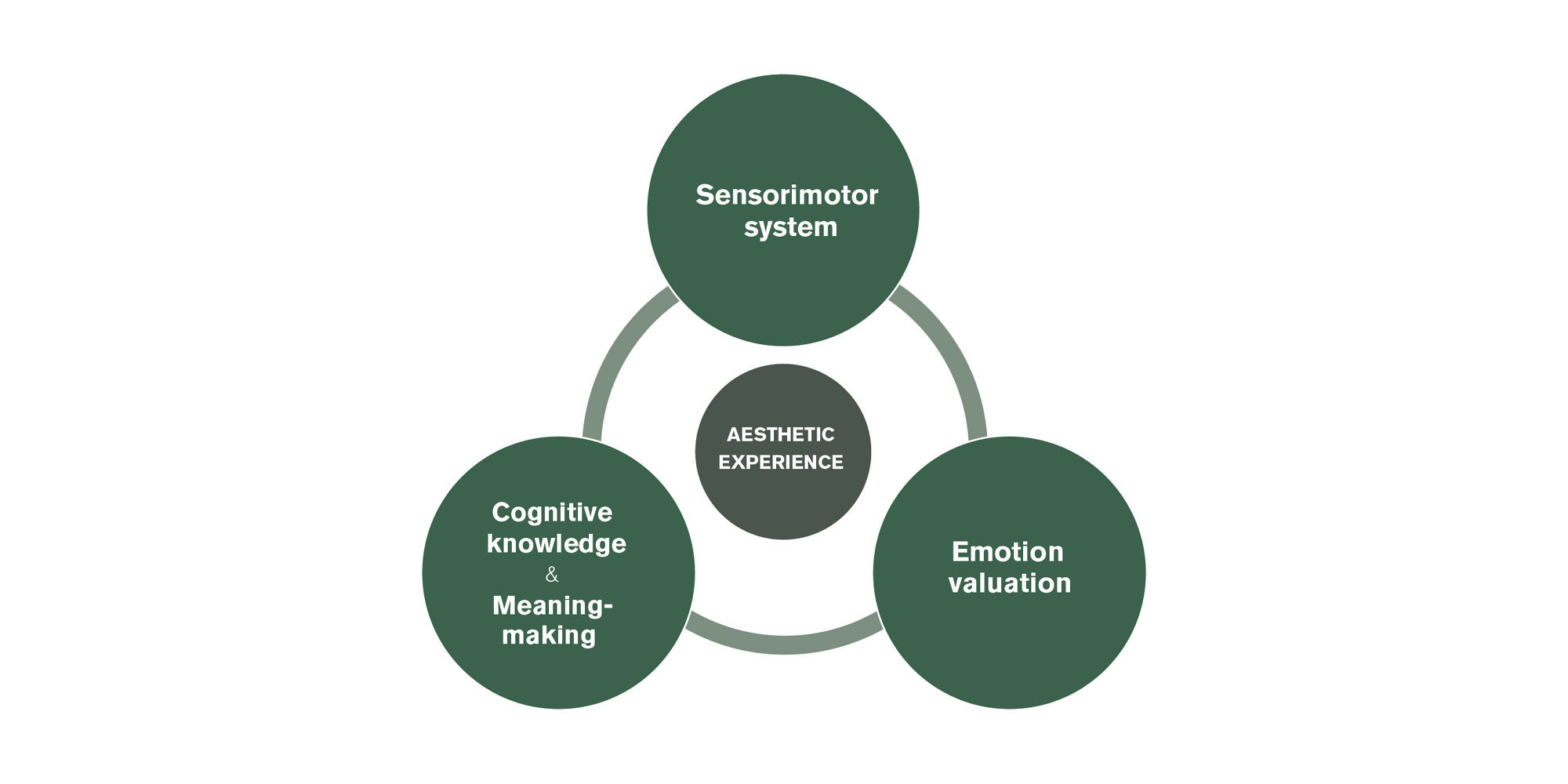

Neuroarchitecture emerges from neuroaesthetics, the study of how the brain responds to aesthetic stimuli. A useful introduction to this field is the research undertaken by Anjan Chatterjee, director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, and Oshin Vartanian, Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto. Chatterjee and Vartanian propose a theoretical model called ‘the aesthetic triad’ which formulates a three-part explanation for how our neural network responds to art: the sensorimotor system, emotion valuation, and cognitive knowledge and meaning-making.

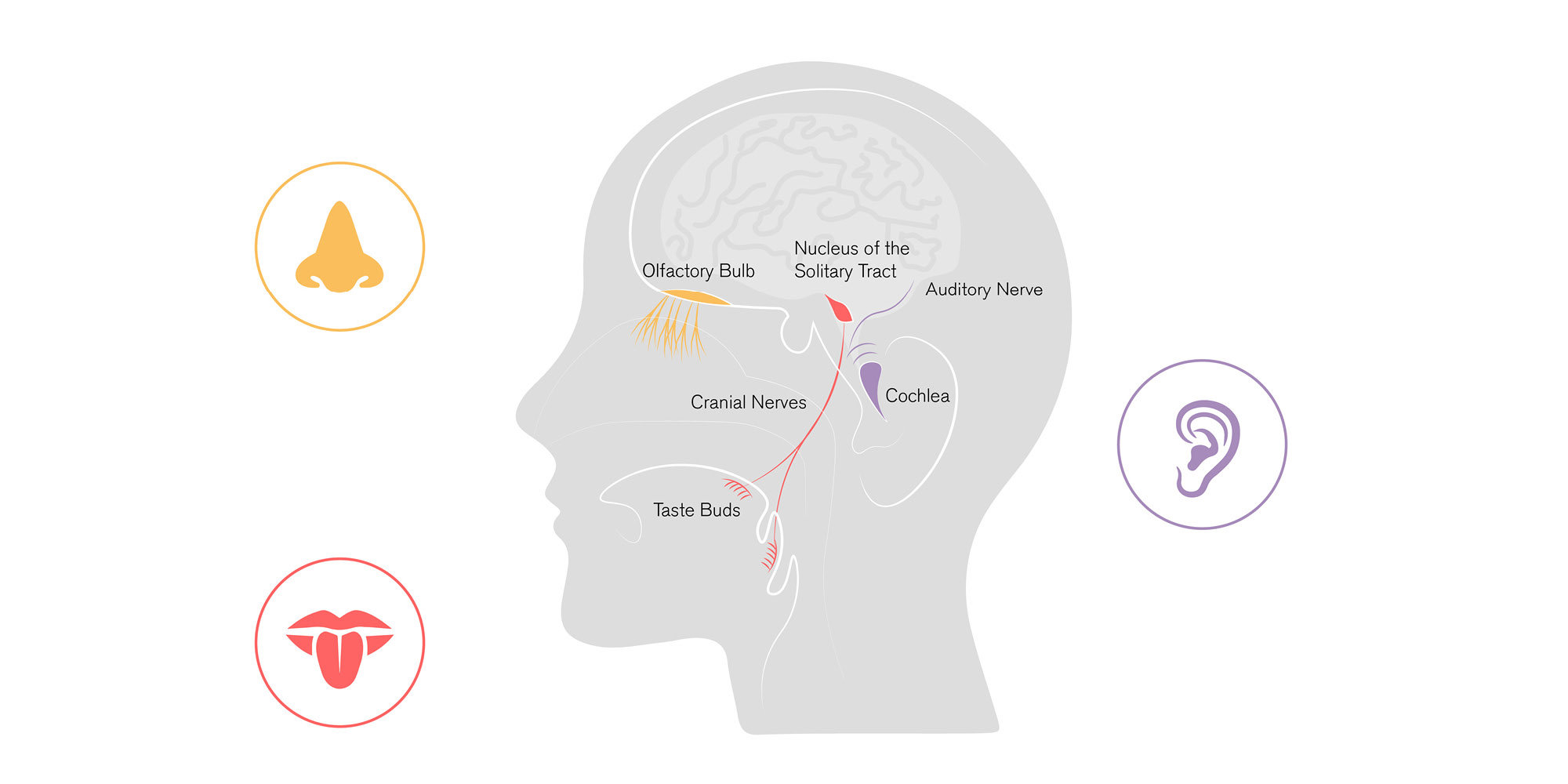

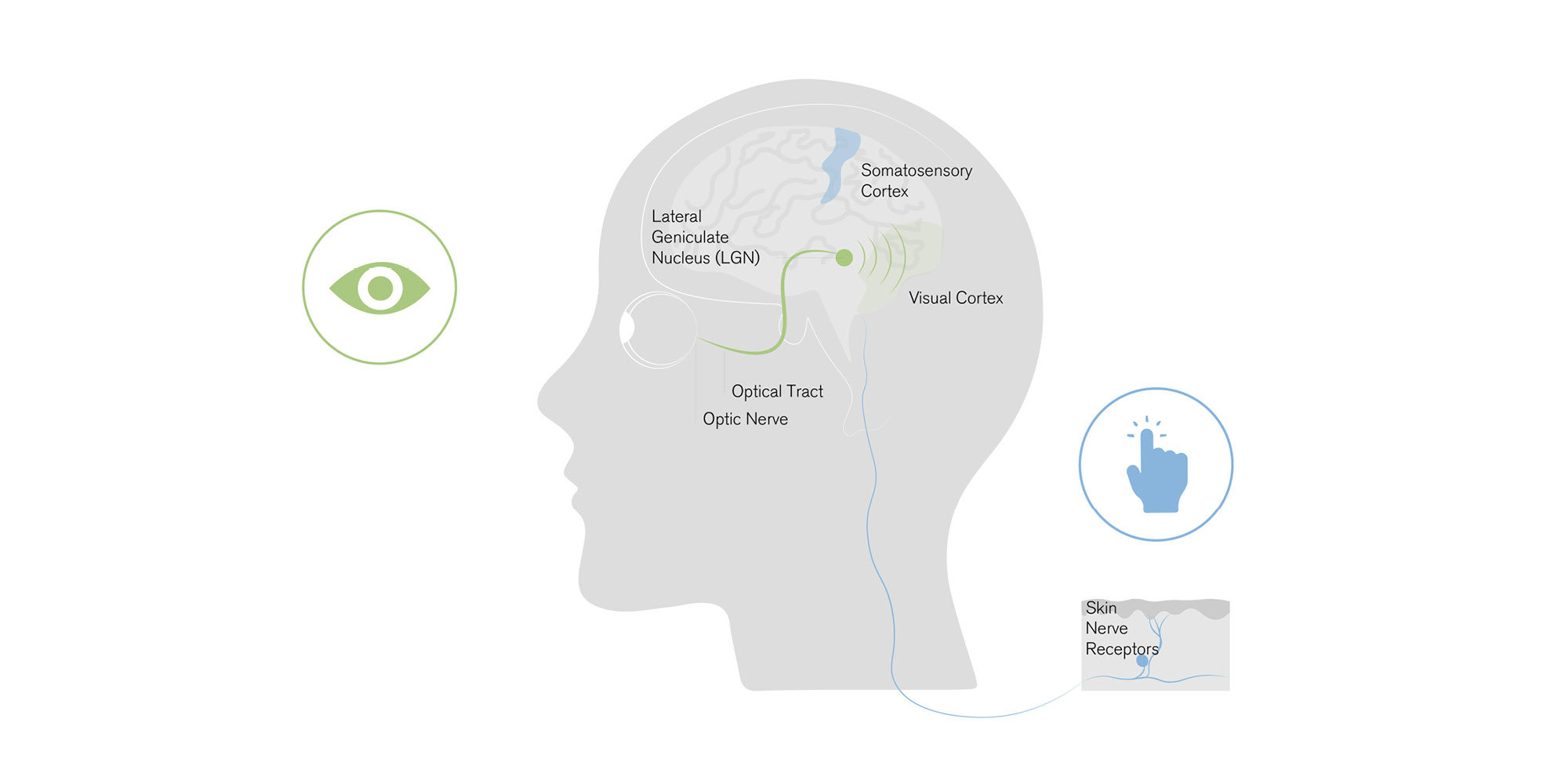

The first aspect of the triad – the ‘sensorimotor system’ – covers our senses, which are closely connected with our memories and emotions, as neuroscientific research can measure and affirm. When we smell something, for example, the information travels through our nose into the olfactory bulb in the brain. This then sends signals to other parts of the brain that control our body, including areas that are associated with emotions and memories – without the main memory centre in our brain necessarily being involved. This extends to our other senses; what we hear, see, touch and taste (and how the brain processes this information) affects how we remember things and feel about them afterwards, and the map of associations that we can form.

Part of the sensorimotor system showing how what we smell travels along the olfactory bulb and reaches internal areas of the brain; what we taste passes through the cranial nerves and the nucleus of the solitary tract; and what we hear reaches our brain passing through the cochlea and the auditory nerve. © Foster + Partners

Part of the sensorimotor system showing how what we see reaches the lateral geniculate nucleus at the back of our brain in a region called the visual cortex; and the information about what we touch passes through our skin and its receptors until it reaches the brain’s somatosensory cortex. © Foster + Partners

The second aspect of the triad is ‘emotion valuation’, located in a network of brain regions associated with reward, pleasure, reinforcement learning and motivation – such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the insula. This system releases neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin, which can make us happy or calm, for example. Research has suggested that our brain responds differently to beauty when compared with unpleasant or neutral stimuli; when people view something beautiful, this system in our brain is more activated and we are motivated to seek similar experiences.

The third element of the triad deals with ‘cognitive knowledge and meaning-making’. At this level, our culture, history and individual experiences influence our aesthetic perception. When looking at a masterpiece like the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci, for example, contextual information and individual art-historical education may modulate neural responses throughout the brain; activation of this extended meaning-knowledge neural system affects our aesthetic experience. This affirms – as philosophical debates touch on – that our aesthetic responses are always part of a broader field of social, political and cultural information.

Defining Neuroarchitecture

This growing domain of neuroaesthetic research has been brought to an architectural context, resulting in the configuration termed neuroarchitecture. Architecture is an artform that exists in physical space, and our buildings, as the Finnish architect and academic Juhani Pallasmaa describes, provide us with ‘perceptual frames and horizons of understanding’ for the world. Neuroarchitecture asks how these external frames affect and are interpreted by our internal, neurological structures and, as a result, influence our moods and behaviours.

Neuroarchitecture might best be understood as a body of expertise, a tool, that designers can call upon and test their ideas with.

As Fred Gage, an American neuroscientist at the Salk Institute observed: ‘Neuroscience has reached a point in its understanding of the brain and how it is influenced by the environment [such] that neuroscientists can work with architects in their designs for environments that enable people to function at their fullest.’ Increasing attention on neurodiversity, accessibility, and wellbeing in relation to architecture can be reinforced by such research, which can guide us to build more supportive environments.

However, neuroarchitecture should not – and cannot – dictate our designs. As Italian cognitive neuroscientist, Vittorio Gallese, reminds:

I don’t think we can say anything interesting if what we say contradicts what we know about the function of the brain. But the brain, in itself, falls short of accounting for our diverse range of social and cultural activities.

Instead, neuroarchitecture might best be understood as a body of expertise, a tool, that designers can call upon and test their ideas with. As is the case with architectural design more generally, which integrates many disciplines at once, neuroarchitecture is part of a broader design ecology. It is an interdisciplinary strategy.

Representing the Mind

As part of our research into the potential of neuroarchitecture, Foster + Partners’ Specialist Modelling Group (SMG) has begun to explore the theories of the likes of Gage and Gallese: how can we negotiate between what is outside our body and inside our brain? What is consciously perceived and what is unconscious but still taking place? How can we artfully represent this situation?

Our electrical signals can, with technology, be mapped. These maps formulate something akin to an architecture of the mind, a visual and spatial representation of how we inhabit ourselves.

SMG has recently collaborated with Amelia Peng, an MA Textiles student at the Royal College of Art, along with musicians and composers from the Royal College of Music and the textile weaver Dreamlux, to create an installation for the 2023 London Design Biennale called Inner Peace. The Inner Peace pavilion harnessed the therapeutic qualities of music and textiles to create a transformative experience that was accessible to people across the neurological spectrum.

The installation was a spectacular textile waterfall set against the backdrop of the Nelson Stair at Somerset House, designed in a Neo-Palladian style by the Swedish-Scottish architect Sir William Chambers. Visitors were invited to listen to music while wearing an EEG (electroencephalogram) headset that recorded their brain waves and visually translated them in colour and in light onto the fabric installation. They were also translated into live-generated natural sounds, like birdsong or flowing rivers, to promote relaxation through multisensory engagement.

By combining smart textiles, data science and neuroscience, this project aimed to explore the possibility of using cutting-edge technology to design more inclusive environments. And, as well as making an aesthetic event of the brain and its internal circuitry, the installation is also a useful demonstration of how neuroarchitecture works across a range of disciplines, requiring expertise from multiple fields.

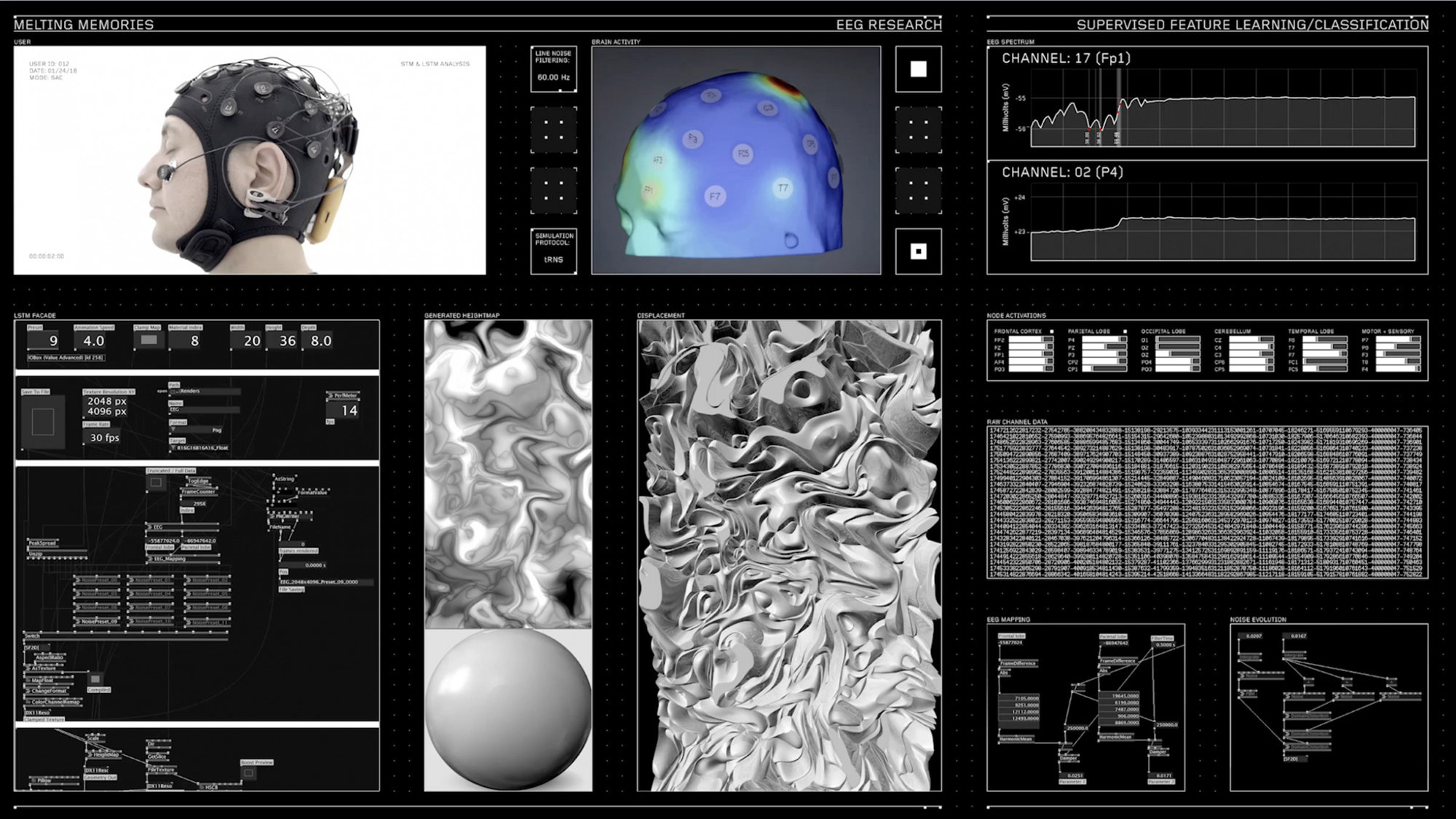

Beyond this neuroarchitectural experimentation at Foster + Partners, others, such as the Turkish-American new-media artist Refik Anadol, are exploring the aesthetics of machine intelligence, and are translating neurological activity into visual images and tactile forms. In an experiment with these advanced technology tools, provided by the Neuroscape Laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco, Anadol collected data ‘on the neural mechanisms of cognitive control from an EEG (electroencephalogram) that measures changes in brainwave activity and provides evidence of how the brain functions over time.’

In Melting Memories, participants were instructed to focus on specific long-term memories during an EEG recording process. This data constitutes ‘the building blocks for the unique algorithms that the artist needs for the multi-dimensional visual structures on display.’

Melting Memories by Refik Anadol, Istanbul, 2018. The project considers ‘the materiality of remembering’ at the intersection of advanced technology and contemporary art. © Refik Anadol Studio

Foster + Partners’ experiments with Inner Peace, and the work of artists like Anadol, reminds us that we are comprised of networks of associations, of electrical processes that can, with technology, be mapped. These maps formulate something akin to an architecture of the mind, a visual and spatial representation of how we inhabit ourselves. The artistic reversal in these works – which brings the inside out – reaffirms the scientific aspects of neuroarchitecture. It reminds us of the complexity of the brain-body system, its constant calibration based on internal and external factors, and its broader implication and orientation in space.

Neuroarchitecture as Design Tool

Alongside its conceptual and artistic appeal, neuroarchitecture provide us with practical frameworks for planning and evaluating spatial environments. Chatterjee, Alex Coburn, and Adam Weinberger suggest in ‘The neuroaesthetics of architectural spaces,’ that the neurological experience of architectural falls into three broad components. The first is coherence: how organised and legible is the space? The second is fascination: is this space interesting, does it make me want to explore? And the third is hominess – how safe and comfortable do I feel in a space? These components can be expressed through geometries, scales, dimensions, lighting, materials, colours, odours or acoustic properties, and they are weighted differently based on what we are designing. The factors that architects should prioritise when designing a hospital, for example, are different than for an office, or a school.

Such research-derived frameworks affirm that design is not only about space but its inhabitants. Neuroarchitecture can be a valuable contributor to the design process, and its study of the functional relationship between the brain-body system and the architectural experience can be harnessed in a variety of ways. Neuroarchitecture can support creative thinking and encourage us to think flexibly. It can also redirect us from design choices that might limit, exclude or harm people.

As Suzan Ucmaklioglu, Inclusive Design Specialist at Foster + Partners, adds:

By considering factors like sensory comfort, wayfinding clarity, adaptable layouts, and stress reduction, this approach can lead to reduced sensory overload, improved navigation, clarity and independent decision making, all of which embrace the different neurocognitive profiles of the human experience. Neuroarchitecture as a design tool plays a pivotal role in promoting a more accessible and welcoming built environment – which benefits everyone.

Emotional Mapping: An in-house study

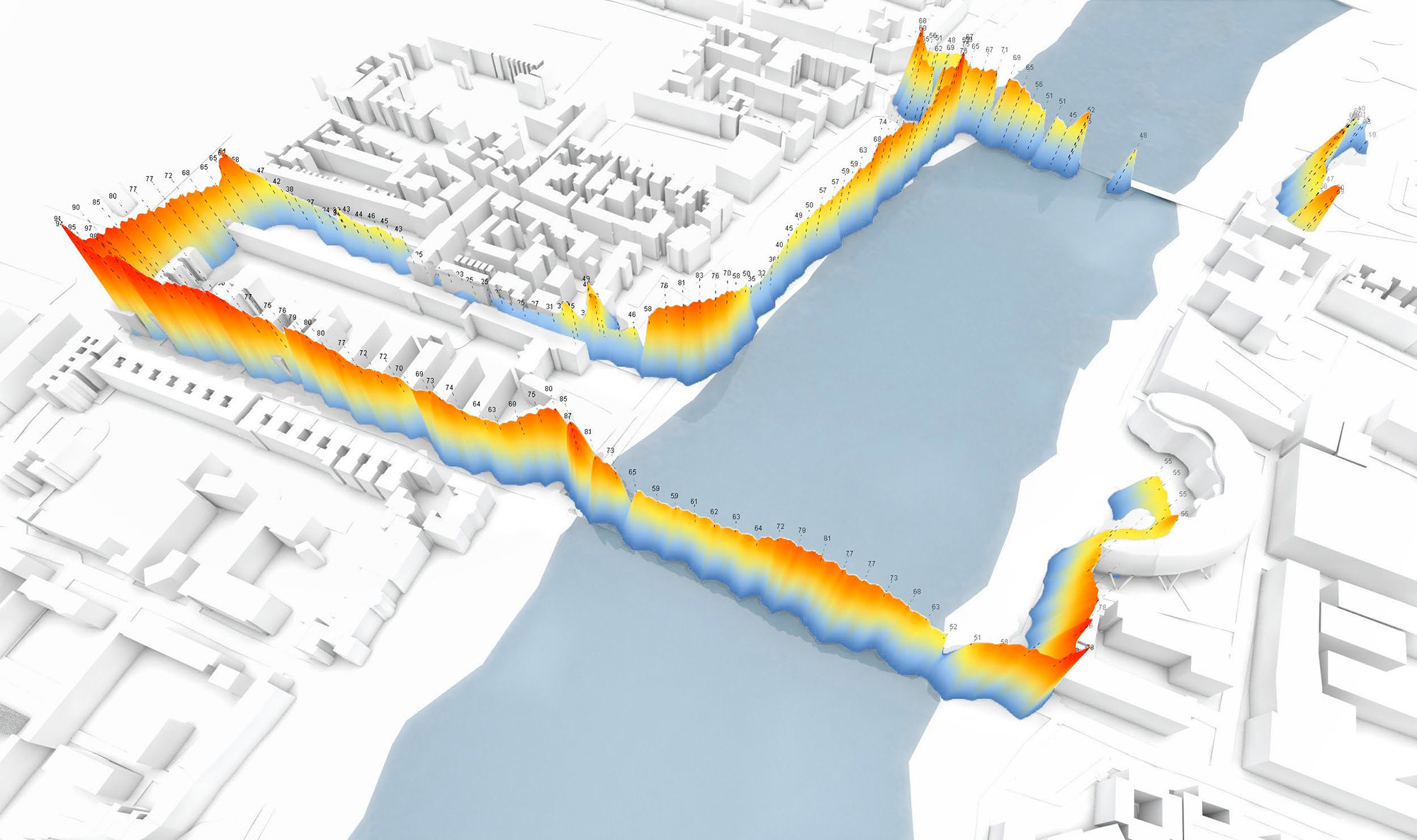

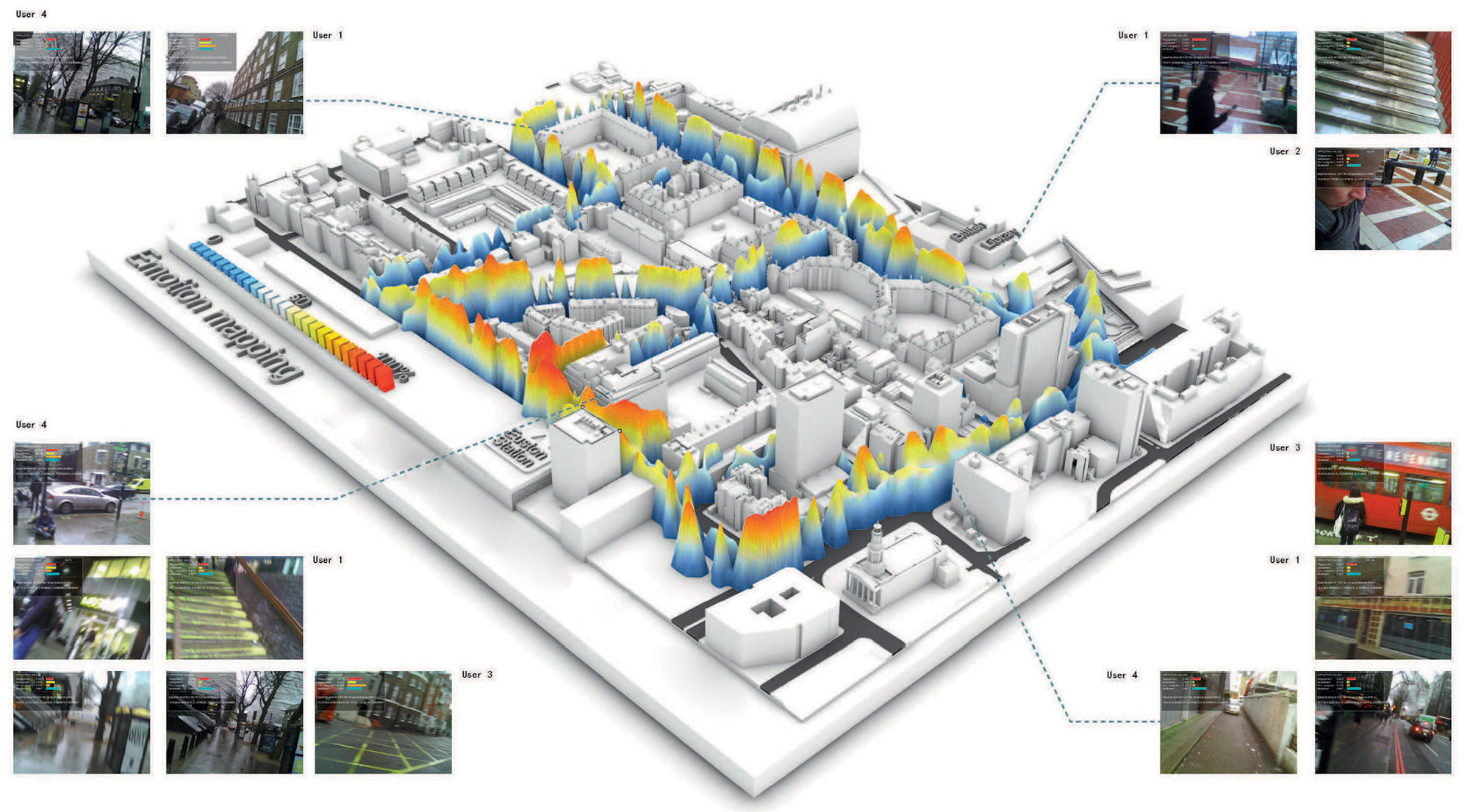

Foster + Partners has conducted neuroarchitectural research in an urban context that registers some of these questions and possibilities. One study carried out by SMG measured people’s reactions to different urban elements as they walked around London – near Foster + Partners’ campus in Battersea, and between Euston Road Station and the British Library in Camden.

Participants’ stress, excitement and meditative levels were recorded using an EEG headset. These levels changed with the urban fabric, as people moved through crowded or confined areas into more open spaces.

Initial study of stress levels around Foster + Partners’ campus in Battersea, London. © Foster + Partners

This project aimed to scientifically track something as seemingly subjective as a participant’s mood as they walked through a changing urban environment. Without negating the subjectivity of our experience, certain common responses to architectural patterns can be mapped and agreed upon – as the resultant diagrams show.

Penn Patient Pavilion: Outside-in

Such frameworks are growing increasingly relevant in the healthcare sector. Projects such as Foster + Partners’ Pavilion at the University of Pennsylvania (2021), a patient care facility connected with Penn Medicine, are amenable to such neuroarchitectural readings. Various strategies in this project – from lighting design, artistic detailing and layout – can be explained, in neuroarchitectural terms, as design decisions that support our bodies and our minds.

The Penn Pavilion accommodates an impressive, cutting-edge range of research and care facilities. Comprising 500 private patient rooms with adjustable acuity levels, from intensive care units to fundamental in-patient amenities, the facility offers ample space for patient families to stay overnight. The Pavilion’s design also connects the outside and inside by prioritising natural light and vistas for patients, visitors and staff. This contributes to a calming atmosphere, since constant artificial lighting can disrupt circadian rhythms, heightening stress and confusion.

Penn Patient Pavilion, University of Pennsylvania. The Pavilion was designed with the nearby Penn Museum in mind, adopting a curved exterior that respects the existing urban architecture. A pedestrianised route to the train station was also formed as part of a broader urban plan that connected the Pavilion with the surrounding area. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The building's distinct and adaptable planning system divides it into distinct ‘neighbourhoods,’ creating a more intimate and personalised atmosphere to counter the stereotypical impersonality of a hospital environment. Each floor also incorporates a ‘living room’ intended for visitors accompanying patients to bring an element of domestic and social security to a generally unfamiliar, potentially stressful environment. Similar strategies were adopted in Maggie’s Manchester (2018), a place where people affected by cancer can find emotional and practical support.

The greenhouse provides a garden retreat, a space for people to gather, to work with their hands and enjoy the therapeutic and biophilic qualities of nature and the outdoors. It will be a space to grow flowers and other produce that can be used at the centre giving the patients a sense of purpose at a time when they may feel at their most vulnerable. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Interior space at Maggie’s Manchester. Home furnishings have been carefully selected to counter the institutional markers of a hospital. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Maggie’s Manchester combines a variety of spaces, from intimate private niches to a library, exercise rooms and places to gather and share a cup of tea. Institutional references, such as corridors and hospital signs have been banished in favour of home-like spaces. As Norman Foster commented on the project:

Our aim … was to create a building that is welcoming, friendly and without any of the institutional references of a hospital or health centre – a light-filled, homely space where people can gather, talk or simply reflect.

Both healthcare architectures, though different in scale and context, intrinsically understand our need for connection and security to heal and be cared for. Neuroarchitecture, which provides a scientific basis for the reciprocal relationship between people and places, can support our architectural intuition and, perhaps, begin to explain why we might feel better as a result.

Neuroaesthetic components can be expressed through geometries, scales, dimensions, lighting, materials, colours, odours or acoustic properties, and they are weighted differently based on what we are designing.

As well as designing in ways that reduce stress, and allow time and space to ‘gather, talk, or simply reflect,’ art also plays a noticeable role in Foster + Partners’ neuroarchitectural approach to design. Artworks are installed in the Penn Pavilion and serve as a vehicle for ‘transmitting cultural values and creating inclusivity,’ as Marcos Nadal and Chatterjee comment, making it quietly appropriate for a building within which people are asked to care for one another. American designer and sculptor Maya Lin’s Decoding the Tree of Life in the atrium of the building uses a spiralling form to communicate across disciplines. As Lin said: ‘I want to make you aware of your surroundings in the Pavilion, in this beacon of scientific advancement, connecting you to the physical and natural world around you while symbolizing the very essence of life – DNA.’

Nigerian-American abstract painter Odil Donald Odita’s colourful, kaleidoscopic mural, Field and Sky accompanies patients and staff as they move through the Pavilion. According to Odita, the mural created ‘an exterior space within an interior – to give the idea of being portalled to the outside.’ Both artworks play with our sense of the body’s relationship to its external environment and ask us to tune into this relationship in new ways.

This attention to how we feel in space, and how we move between spaces, extends to the layout of the Penn Pavilion. Curvilinear exterior and interior forms have been proven to be preferable by researchers including Chatterjee and Vartanian, since curved forms evoke a sense of safety and comfort, in contrast to angular shapes that can elicit feelings of threat or unease.

Both healthcare architectures, though different in scale and context, intrinsically understand our need for connection and security to heal and be cared for.

While the scale and design of the Maggie’s Centre allowed for the removal of ‘hospital’ signage altogether, this was not possible at a building with as comprehensive a care offering as the Penn Pavilion. Instead, careful attention was paid to what wayfinding was required, and the interiors are organized to ensure that individuals are aware of their location at any moment and can navigate through the space with ease. This thoughtful approach minimizes confusion, further contributing to a positive experience for patients, staff and visitors.

Curvilinear shapes are not only a formal and aesthetic feature: they serve a function of reducing stress, supporting wayfinding, and minimising confusion. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Neuroarchitecture brings architectural elements in conversation with our bodies and our nervous systems. It reminds us that we are in a reciprocal, ever-shifting relationship with even the most seemingly inconsequential of spaces, and legitimises long-held ideas around art and architecture’s ability to impact our psychology and physiology. As Foster describes in his appreciation of Lin’s work: ‘Rationalization apart, it is a beautiful and calming presence for patients and those accompanying them.’

Potential Pathways

Working in this direction, SMG and the Workplace Consultancy team at Foster + Partners are collaborating with CW+, an NHS Foundation group at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London. The project, currently underway, aims to measure and record people’s response to spatial parameters and patterns of biophilia in a hospital environment. Variations are measured across physical and virtual reality using a combination of techniques that hail from neuroscience and will provide information on how different conditions affect the body and mind. This not only has applications in a healthcare context; there is potential to bring these findings to other architectural or urban design initiatives to improve wellbeing.

Images of the patient room used for the study in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. The ‘patient’ figure wears an electroencephalogram device (EEG) on their head, eye-tracking glasses, a heart rate variability monitor (HRV) on their chest, and an electrodermal activity sensor (EAS) on their fingers. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Images of the patient room used for the study in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. The ‘patient’ figure wears an electroencephalogram device (EEG) on their head, eye-tracking glasses, a heart rate variability monitor (HRV) on their chest, and an electrodermal activity sensor (EAS) on their fingers. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Images of the patient room used for the study in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. The ‘patient’ figure wears an electroencephalogram device (EEG) on their head, eye-tracking glasses, a heart rate variability monitor (HRV) on their chest, and an electrodermal activity sensor (EAS) on their fingers. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Images of the patient room used for the study in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. The ‘patient’ figure wears an electroencephalogram device (EEG) on their head, eye-tracking glasses, a heart rate variability monitor (HRV) on their chest, and an electrodermal activity sensor (EAS) on their fingers. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Despite the exciting prospects of these experiments for developing guidelines for architects, particularly healthcare designers, we can never exactly predict or measure someone’s response to an environment. Neuroarchitecture is less about using neuroscience to ‘unlock’ a perfect design scenario, and more about finding promising new ways of designing that tend towards practical and considerate results, while allowing space for individual and subjective experience.

It is neuroarchitecture’s promise, however, that also leaves it prone to misinterpretation. And so, the questions around the future of neuroarchitecture are manifold. Where can the study of the brain lead us and, in turn, our designs? At what stage should neuroarchitecture be implemented in the design process, and why? Who practices neuroarchitecture?

As we work to provide some answers to these problems – and uncover further questions – we can, at least, be sure of a universal truth – there will always exist an interdependence between our minds, bodies, and environments. Where neuroarchitecture offers opportunity is in its potential to provide a framework to approach, measure and test this relationship. The data shows that it can help us to design better, and promise that we might all feel better, too.

Bibliography

• Anadol, R. ‘Melting Memories’

• Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2014). Neuroaesthetics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18 (7), 370-375.

• Chatterjee, A., Coburn, A., & Weinberger, A. (2021). The Neuroaesthetics of Architectural Spaces. Cognitive Processing, 22 (Suppl 1), 115-120.

• Gage, F., Eberhard, J. An Architect and a Neuroscientist Discuss How Neuroscience Can Influence Architectural Design. Neuroscience Quarterly, Fall 2003, 6-7.

• Lin, M. ‘Decoding the Tree of Life’

• Nadal, M., & Chatterjee, A. (2019). Neuroaesthetics and art's diversity and universality. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 10(3), e1487.

• Odita, O. ‘Field and Sky’

• Pallasmaa, J. (2018). Architecture as Experience: The Fusion of the World and the Self. Architectural Research in Finland, 2(1), 9–17.

• Pallasmaa, J., Mallgrave, H., Robinson, S., & Gallese, V. Architecture and Empathy, TWRB Foundation; 2015.

• Vartanian, O., Navarrete, G., Palumbo, L., & Chatterjee, A. (2021). Individual differences in preference for architectural interiors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 77, Article 101668.

Author

Vittoria Falchini and Rosi Pachilova

Author Bio

Vittoria Falchini is a Workplace Consultant at Foster + Partners, specialising in neuroarchitectural psychology. As part of the Workplace Consultancy team and with a background in clinical and environmental psychology, she focuses her work on how our brain functions and processes information, how this affects human behaviour, cognition and experience, and how it is possible to attune humans with the built environment. She joined the practice in 2022 after completing a master’s at IUAV, Venice, on ‘Neuroscience Applied to Architectural Design’. Vittoria is a member of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture and the British Psychological Society. The Workplace Consultancy team is composed of specialists with different expertise from data analyst to healthcare designer, workplace strategist to user experience designer. Their work covers all the phases of a project from the observation and client engagement to development of the brief and building analysis, to future research and user experience, until post occupancy evaluation.

Rosi Pachilova is part of the Workplace Consultancy team at Foster + Partners – a group of designers, analysts and researchers that work with the architecture studios to help address the business objectives and changing requirements of clients. Rosi recently completed her PhD at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, where she studied the effect of ward layouts on work process and communication patterns of healthcare providers, and the subsequent effects on quality of care.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George