‘Bioclimatic architecture’ is an integrated term that combines biological, environmental, and technological disciplines with the design of buildings. From the ancient observation of Vitruvius, via the practical, analogue applications of the Olgyay brothers in the twentieth century, to digital tool application and environmental engineering at Foster + Partners today, the ‘bioclimatic’ approach captures a longstanding philosophy and methodology for designing more sustainable, climate-appropriate, and comfortable architecture.

18th June 2025

Bioclimatic Architecture

Combining multiple disciplines – biology, climate science, architecture, technology and building physics – bioclimatic architecture is a field of practice that acknowledges the essential link between buildings and their climate, and then works with this connection to design in support of people’s comfort.

The mission of architecture has always been the protection of man from the exterior environment and in this case, bioclimatic architecture attempts to achieve human thermal comfort by interacting energetically with the exterior climate. Architecture has always held the objective of climate comfort and this has been inherent to architecture from its origins.

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 49, 2015

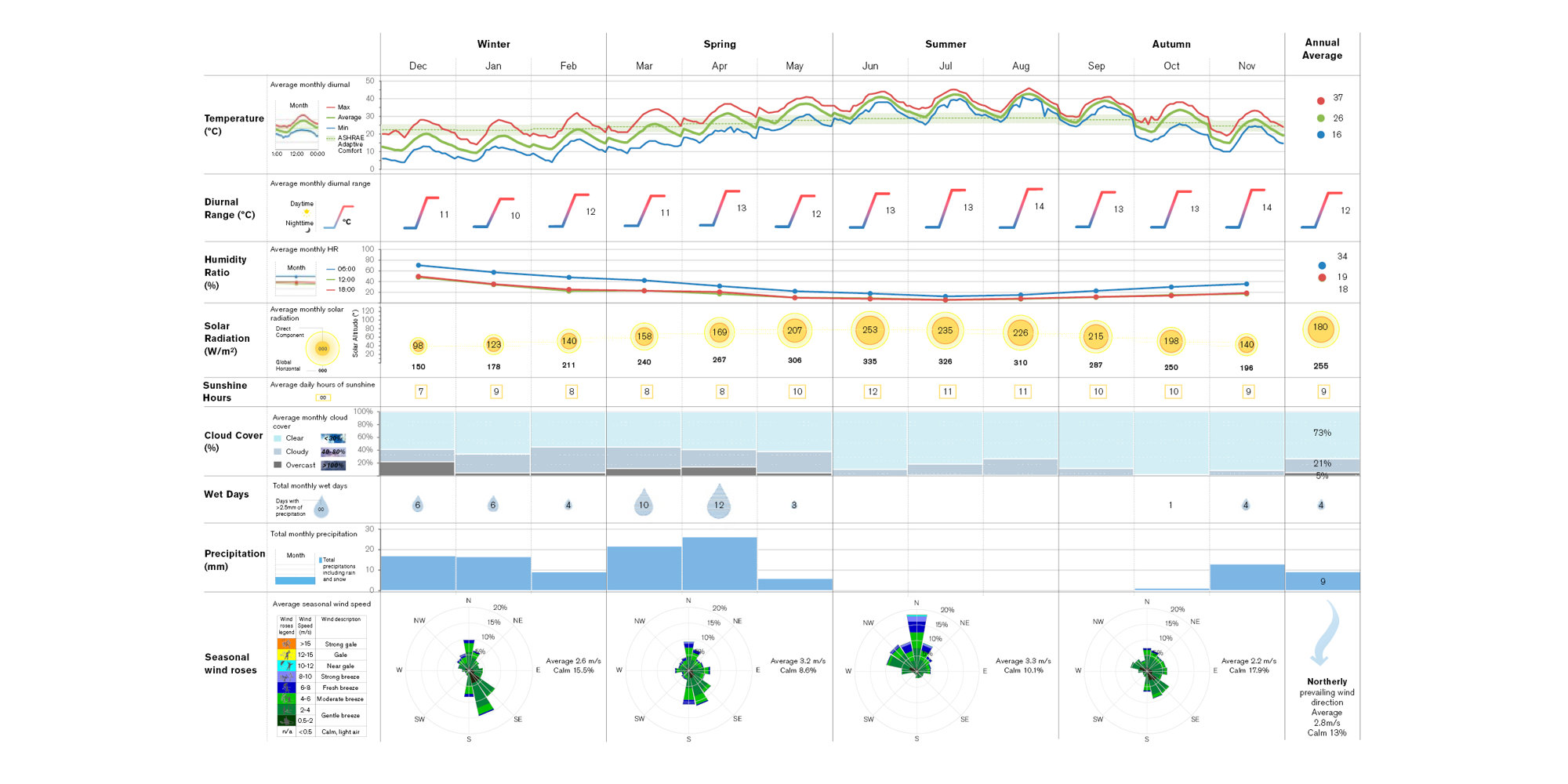

Climate – which is composed of air temperature, solar radiation, cloud coverage, wind, rainfall, and humidity – informs how and why buildings and outdoors spaces are constructed, as well as how they adapt over time, thus shaping regional forms and design approaches.

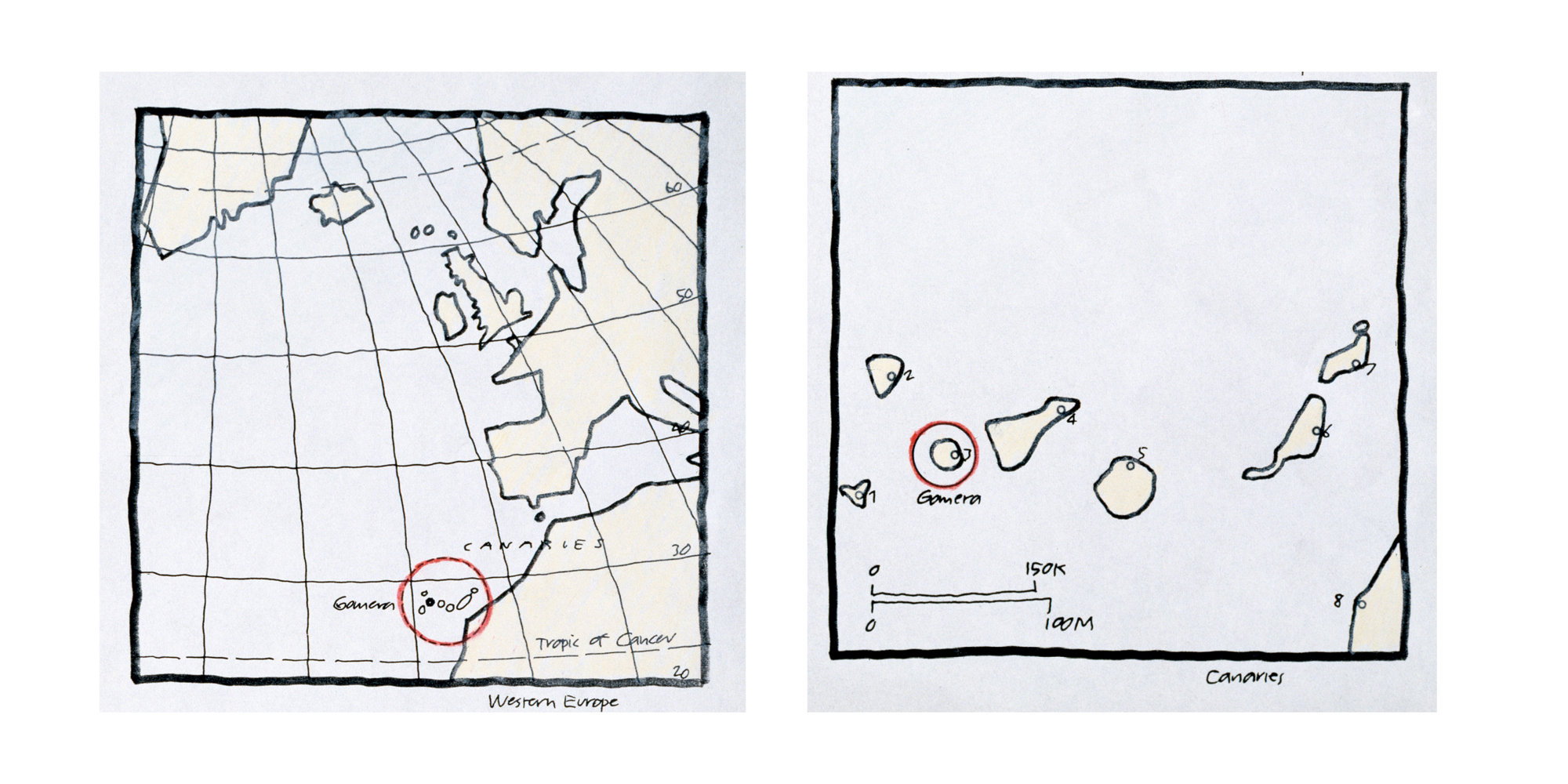

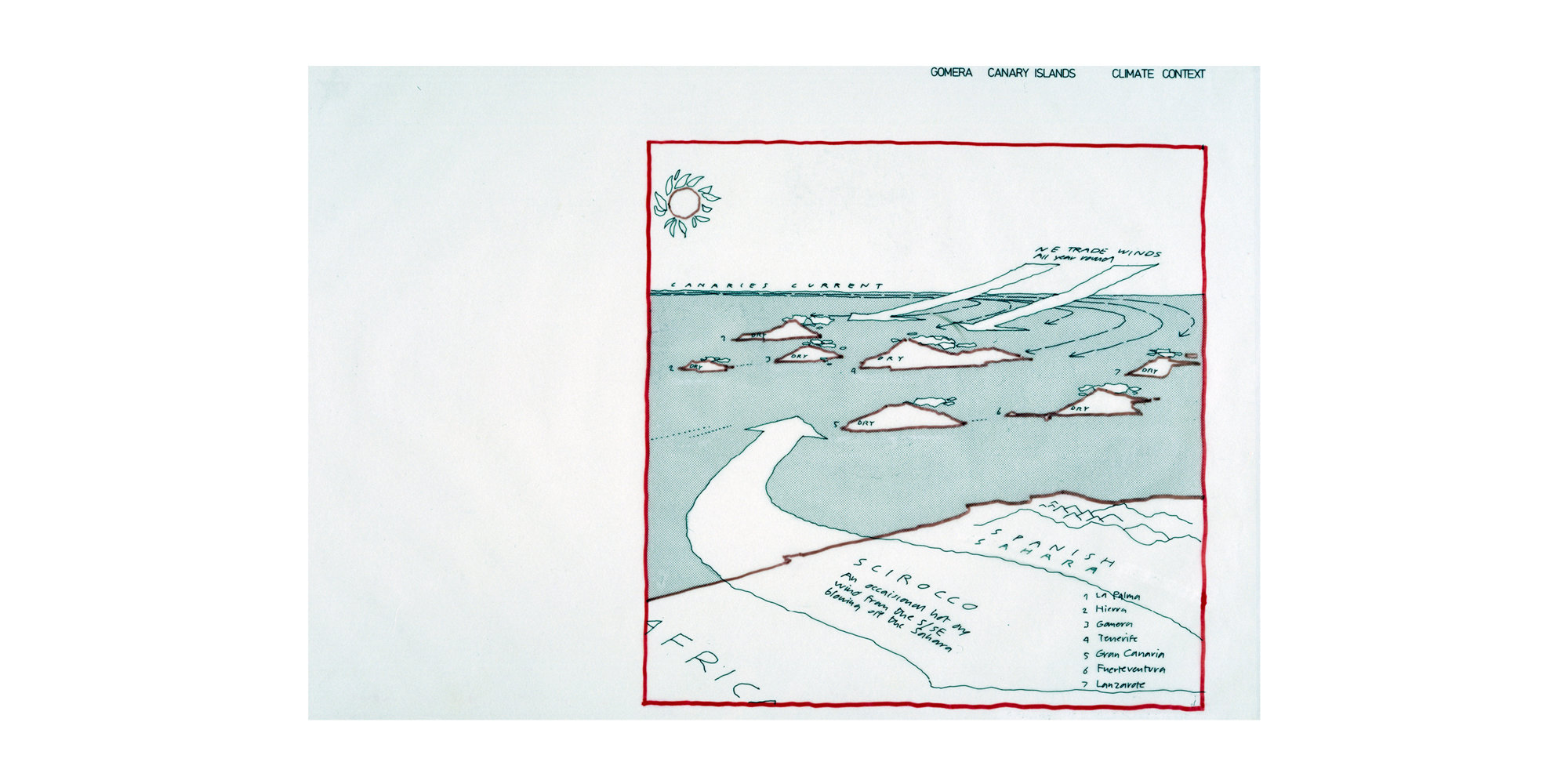

Foster + Partners has long understood the importance of climate in design considerations, long before a ‘green agenda’ or push for vernacular engagement entered mainstream architectural discourse. The practice’s 1975 study of Gomera in the Canary Islands, for example, paid close attention to the climate of the region, and how a sustainable development might be realised.

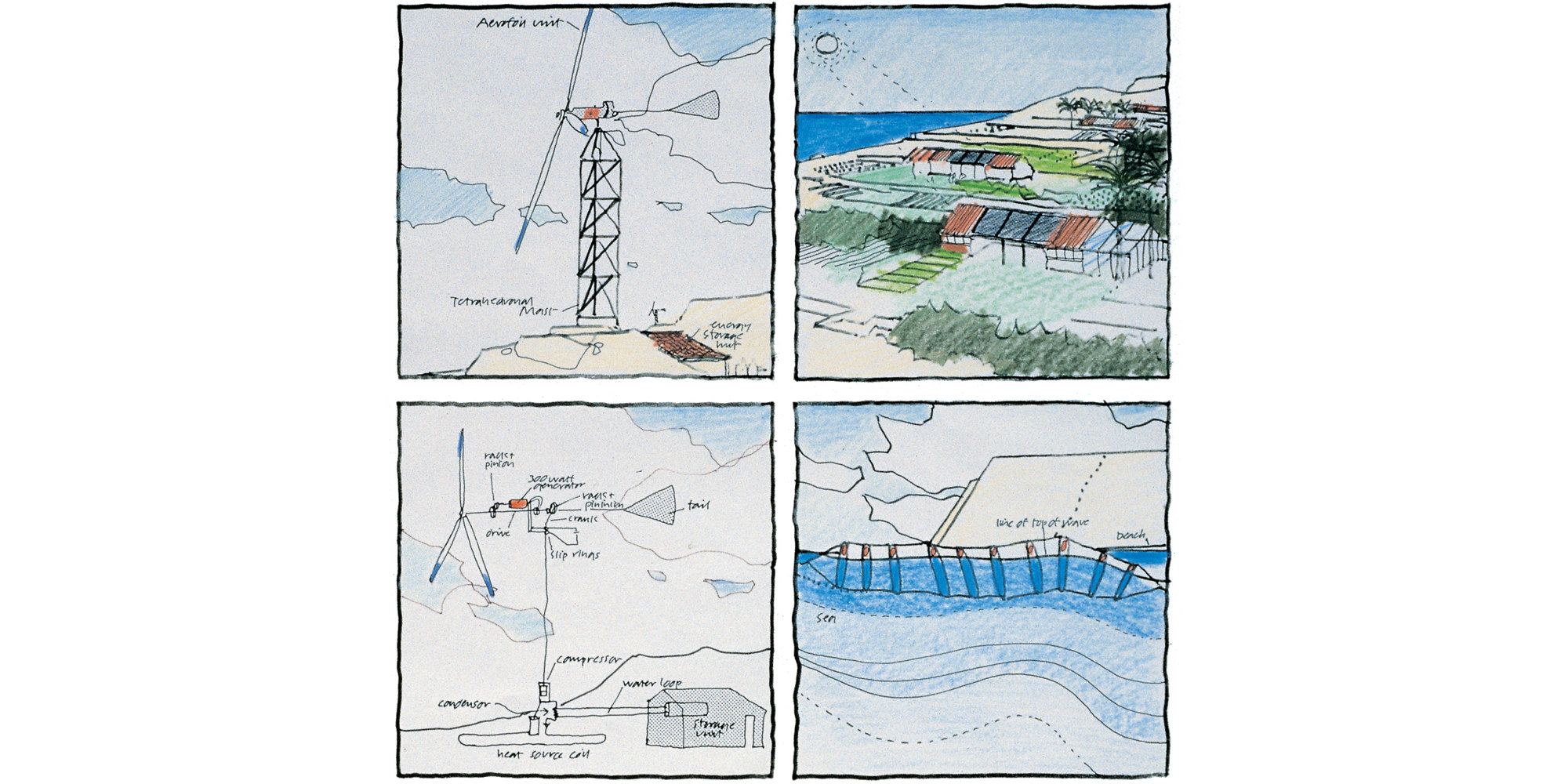

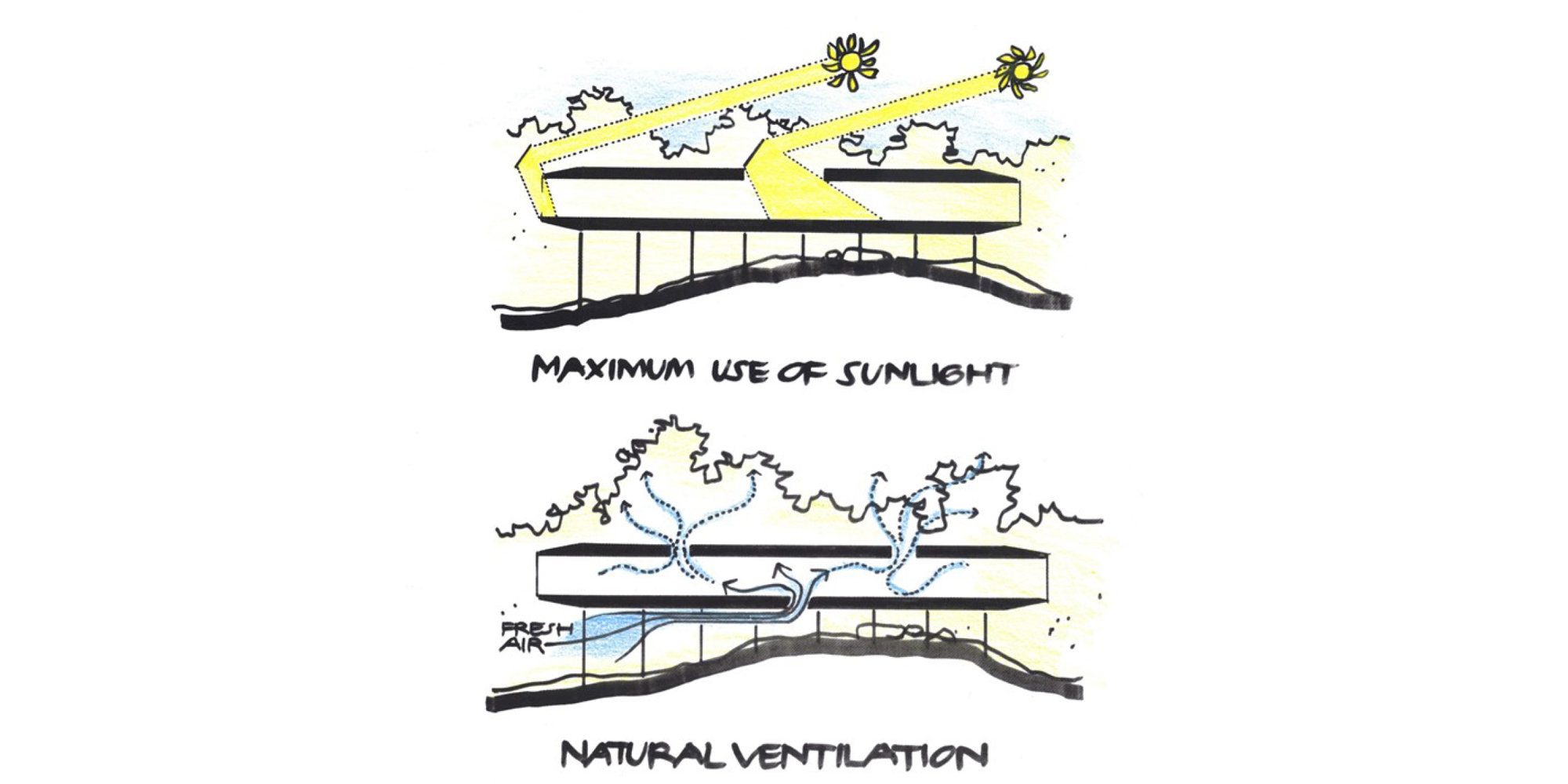

Studies of original settlements highlighted a single-aspect dwelling that looked out to the sun and had as much shaded area outside as it had habitable area inside. These ingredients generated a high-density, low-rise solution that responded well to the island’s climate. This approach was reinforced by alternative methods of energy generation and water collection. Constant sunshine and steady winds made the island a natural test-bed for solar and wind power, while other systems, such as methane production from domestic waste, were explored to reduce dependence on imported oil.

Gomera’s climate was also considered in relation to leisure activities on the island – such as sailing, hiking, and horse riding. These, in turn, required various architectural or landscape interventions to be considered beyond the immediate planning of the ‘dwelling’ design.

The Roots of Bioclimatic Design

Foster + Partners’ study on Gomera taps into an essential link between building and climate – a link that is too often ignored but has, nevertheless, been noted throughout history. In the sixth book of his treatise, De Architectura, written sometime between 20 and 30 BC, Vitruvius noted the link between building and climate, making a case for site-specific design rather than a universal approach.

If our designs for private houses are to be correct, we must at the outset take note of the countries and climates in which they are built. One style of house seems appropriate to build in Egypt, another in Spain, a different kind in Pontus, one still different in Rome, and so on with lands and countries of other characteristics. This is because one part of the earth is directly under the sun's course, another is far away from it, while another lies midway between these two… Designs for houses ought to conform to the nature of the country and to diversities of climate.

Vitruvius, De Architectura

A climate-specific model of design was voiced some two thousand years ago. One inheritor of this view today is a data-driven approach to design which takes into account measurable information about the site’s climate and calculates how a building will behave in response. This data-driven approach might seem relatively recent but has, in fact, been underway throughout the twentieth century. Foster + Partners’ research in Gomera in the 1970s is one example. The field of bioclimatic architecture, which emerged in the decade preceding, is its precursor.

Echoing Vitruvius’ observation that buildings should be differently styled in different locations, the bioclimatic architecture argues that a specific climate should guide the form, style, and engineering of a design, to improve the comfort and wellbeing of its occupants.

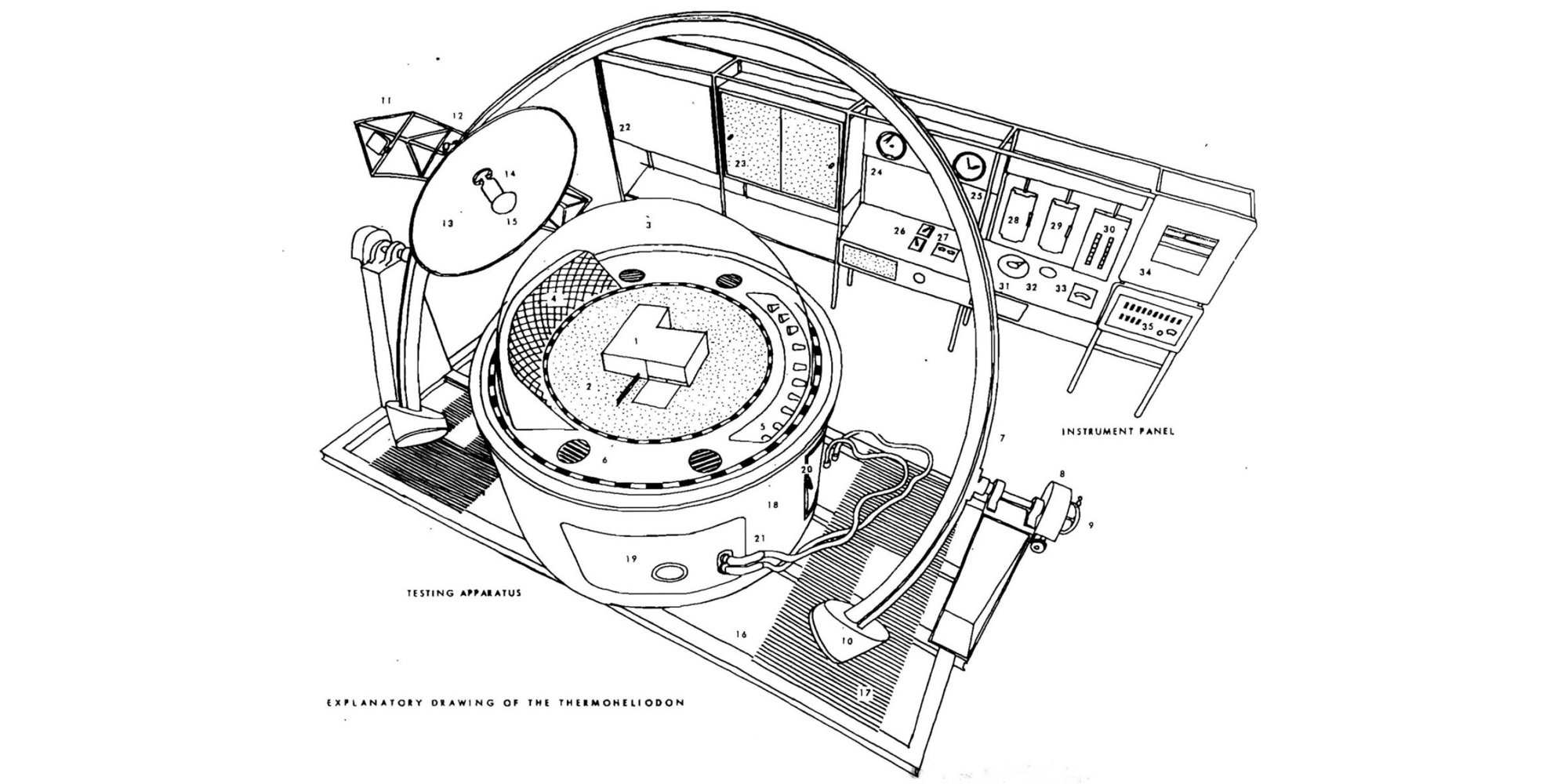

The work of the Olgyay brothers – twin Hungarian architects Aladar and Victor Olgyay – in the 1950s and ’60s, as well as other practitioners working in different locations, reveals striking parallels between bioclimatic architecture’s initially analogue methods of measuring light, shading, and airflow, and the digital methods that environmental engineers and architect use today. Interestingly, the work of Foster + Partners, which takes hold a generation after the Olgyays, adopts and extends much of the principles of bioclimatic design, leveraging climate research and building technology in a variety of architectural and urban projects.

International style versus the bioclimatic approach: Diverging strands of enquiry

How did bioclimatic approach emerge in the twentieth century? The relationship between climate and architecture was significantly obstructed with the invention of air conditioning in 1903. The integration of mechanical heating and cooling systems in design, and the subsequent endorsement of an international indoor climate, is a well-known architectural narrative of the twentieth century. As early as 1906, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building promoted a ‘hermetically sealed’ box that contained a controlled indoor climate; by the end of the century, many new buildings across regions – regardless of external climate – had come to rely heavily on such mechanical systems for temperature control. As architectural critic John Reynolds put it: ‘Let the machinery handle it.’

Followers of the International Style largely endorsed the mechanical revolution as it progressed. In 1969, architectural critic Reyner Banham posited that people could ‘live under low ceilings in the humid tropics, behind thin walls in the arctic, and under uninsulated roofs in the desert.’ By the oil crisis of 1973, however, the energy consumption of these systems came under critique, and more passive measures were beginning to be reconsidered. This was soon reflected in new ways of measuring and testing the energy efficiency and performance of these buildings, with environmental standards such as LEED and BREEAM introduced in the 1990s.

Simultaneous with the bold claims of the International Style and the rise of mechanical systems, the field of bioclimatic architecture, which emerged counter to this dominant culture in the mid-century, sought an alternative approach. It argued that design itself can create a foundation for the regulation of a building’s internal climate, through which mechanical systems can be added to design hybrid systems that are tailored to specific climates in a responsive manner.

The Olgyay Brothers and the Emergence of Bioclimatic Architecture

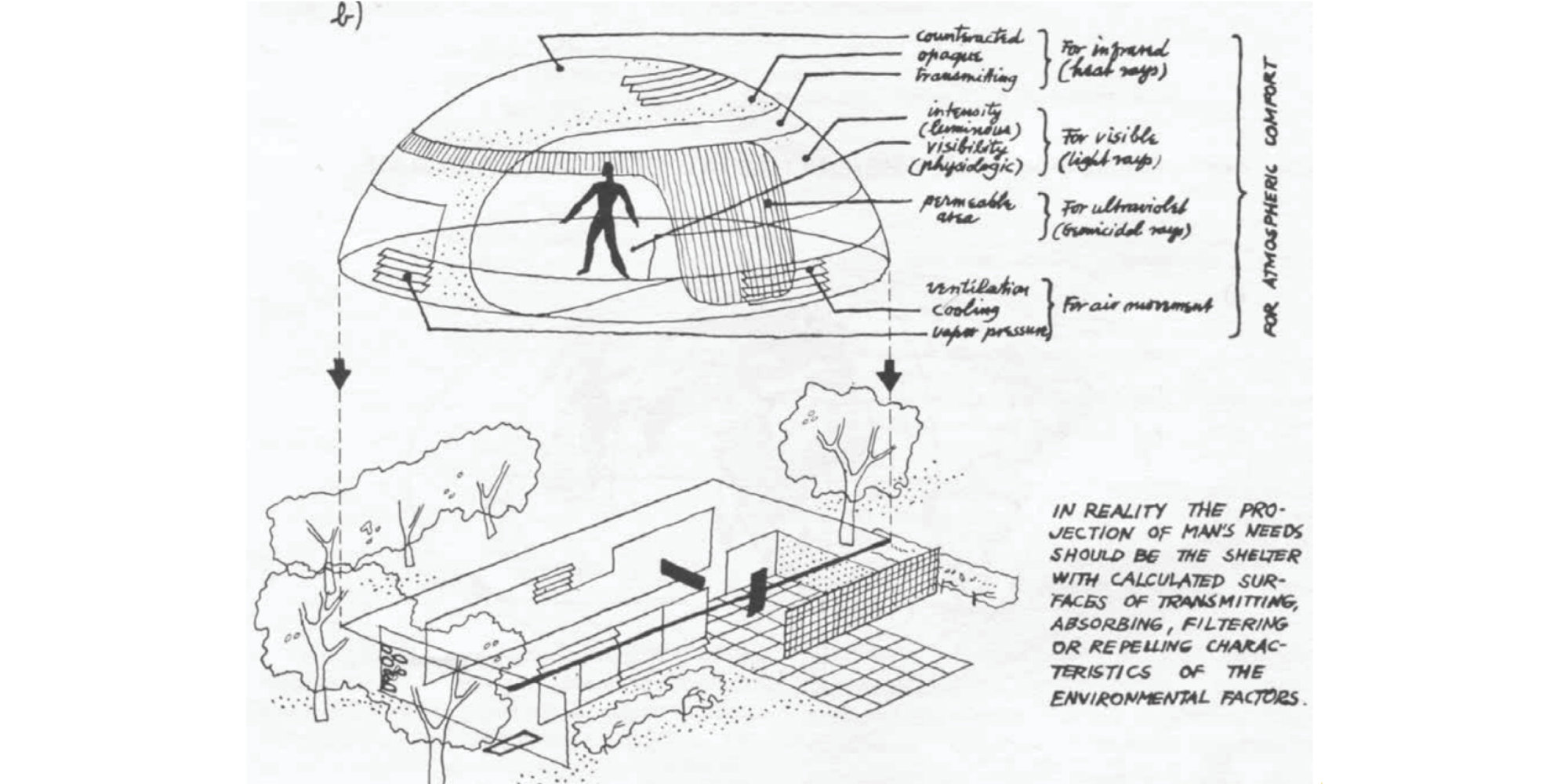

The work of the Olgyay brothers offers some of the earliest examples of design that systematically integrates localised climate information and calculations into a design workflow, influencing the massing of the structure, facade elements, internal spatial organisation, external layouts, and aesthetic identities of a project. Their illustrations highlight not only these technical aspects of design but also how they link with people’s experience – the ‘comfort’ of the building.

Since the beginning of their careers in Hungary, Victor and Aladar exhibited an intense curiosity about the natural world and its interplay with architecture. The pair designed and built over forty projects in Hungary before World War II that demonstrated a comprehensive application of environmental design and analysis.

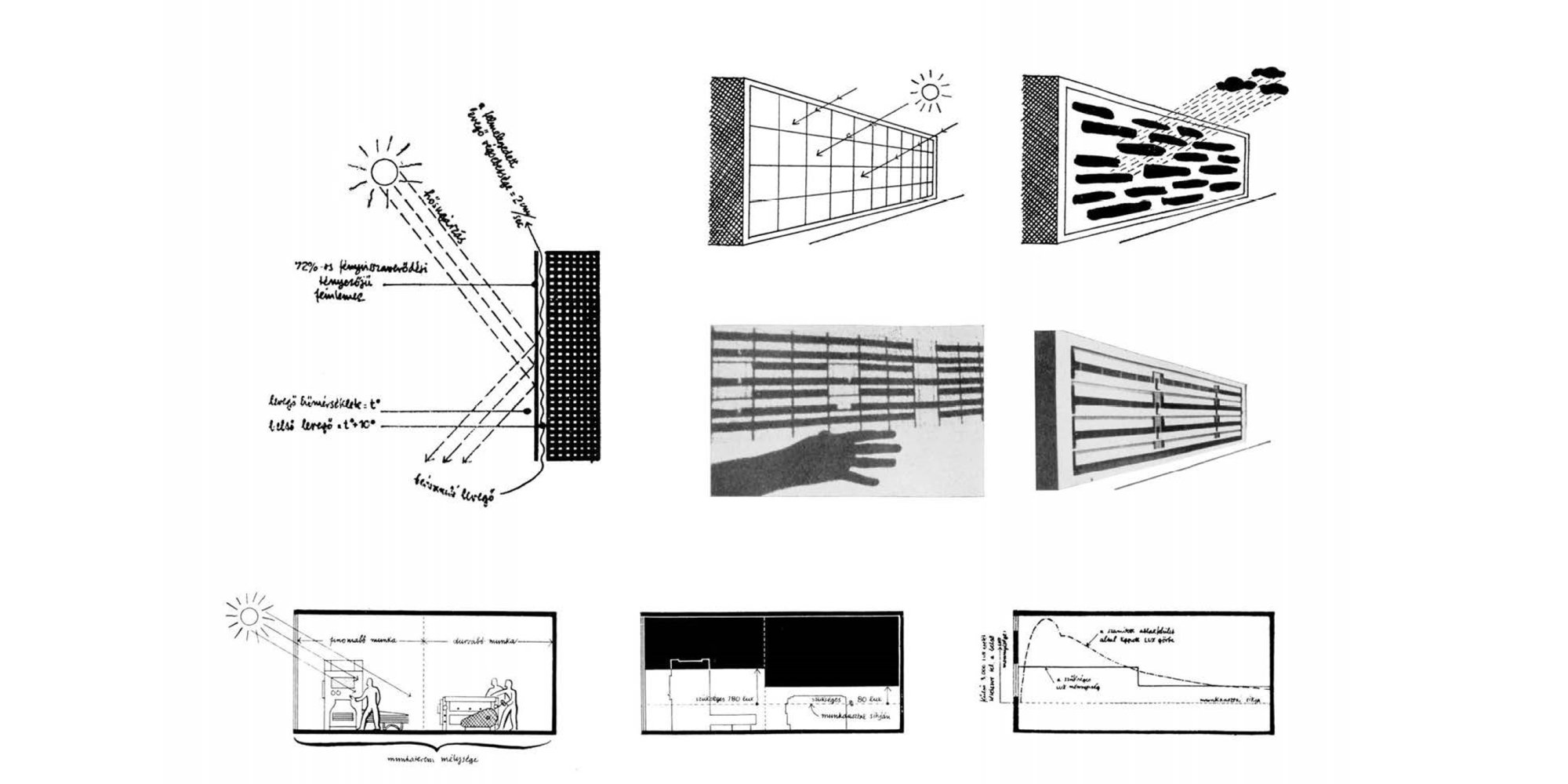

One of the brothers’ most popular works was the Stühmer Chocolate Factory in Hungary, which was completed in 1941. This project showcased innovative on-site calculations and design solutions, all accomplished without the sophisticated software available today. The brother conducted extensive daylight model testing to inform the size and location of fenestration under various daylight conditions and to plan the layout while coordinating the facility's operational needs with environmental conditions. In addition, they designed an ingenious ventilating facade to passively mitigate solar heat gain.

Not surprisingly, these environmental investigations resulted in an aesthetic much in line with the prevailing modernist style. In massing, detail, and material, the chocolate factory is clearly a rationalist International style building, but unlike other buildings of the time, its design was derived from and grounded in rigorous climatic analysis.

Victor W. Olgyay (Son of Victor Olgyay) ‘Introduction’ to Design With Climate

The Olgyay brothers were not alone; other architects in different parts of the world similarly adopted a bioclimatic approach that rejected a widespread International Style in favour of more local, vernacular forms.

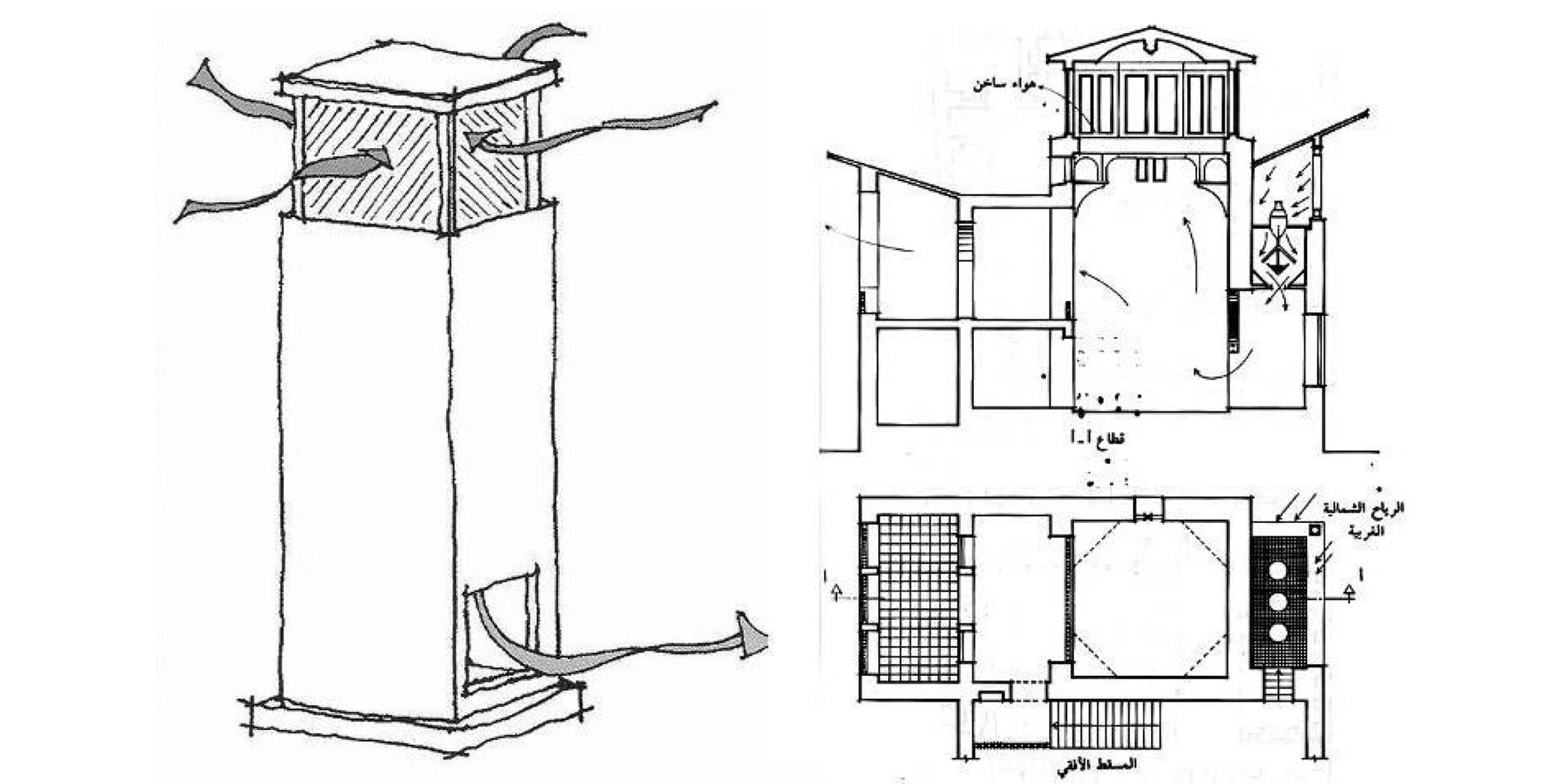

In Egypt, for example, Hassan Fathy (1900-1989) rejected the international modernist approach, which sought to unify architectural language under a single pattern. Instead, he advocated for incorporating new technologies, ensuring they were adapted to the cultural authenticity and specific climatic conditions of the site. He studied the simple yet effective ways climate shapes architectural forms – specifically in hot and arid climates. For him, architectural form holds meaning only within the context of its environment. Fathy highlighted two key factors in achieving indoor comfort: first, the need for materials in walls and roofs that minimise heat conduction; and second, careful attention to air movement and ventilation. He practised bioclimatic architecture through elements such as courtyards, iwans (three-sided walled halls), malqaf (wind catchers), vaulted ceilings, domes, mashrabiyyas (wooden lattice-filled openings used to reduce glare while allowing breezes to pass through), projecting balconies, overhangs casting long shadows and local building materials. Due to the limited computational tools available at the time, Fathy tested seven chambers with various elements built by using different techniques to evaluate their suitability for Egypt’s climatic conditions. Additionally, the shortages of steel and timber in Egypt after World War Two allowed Fathy to take advantage of local earth as a primary building material, as well as traditional construction methods.

Wind catcher as drawn by Hassan Fathy. Via: "Improving the Thermal Performance of Mosque Buildings with the Assistance of Passive Cooling Systems"

Domes in New Baris Village by Hassan Fathy. © Viola Bertini. Source: Hassan Fathy, Building in the Desert in New Baris - Senses Atlas

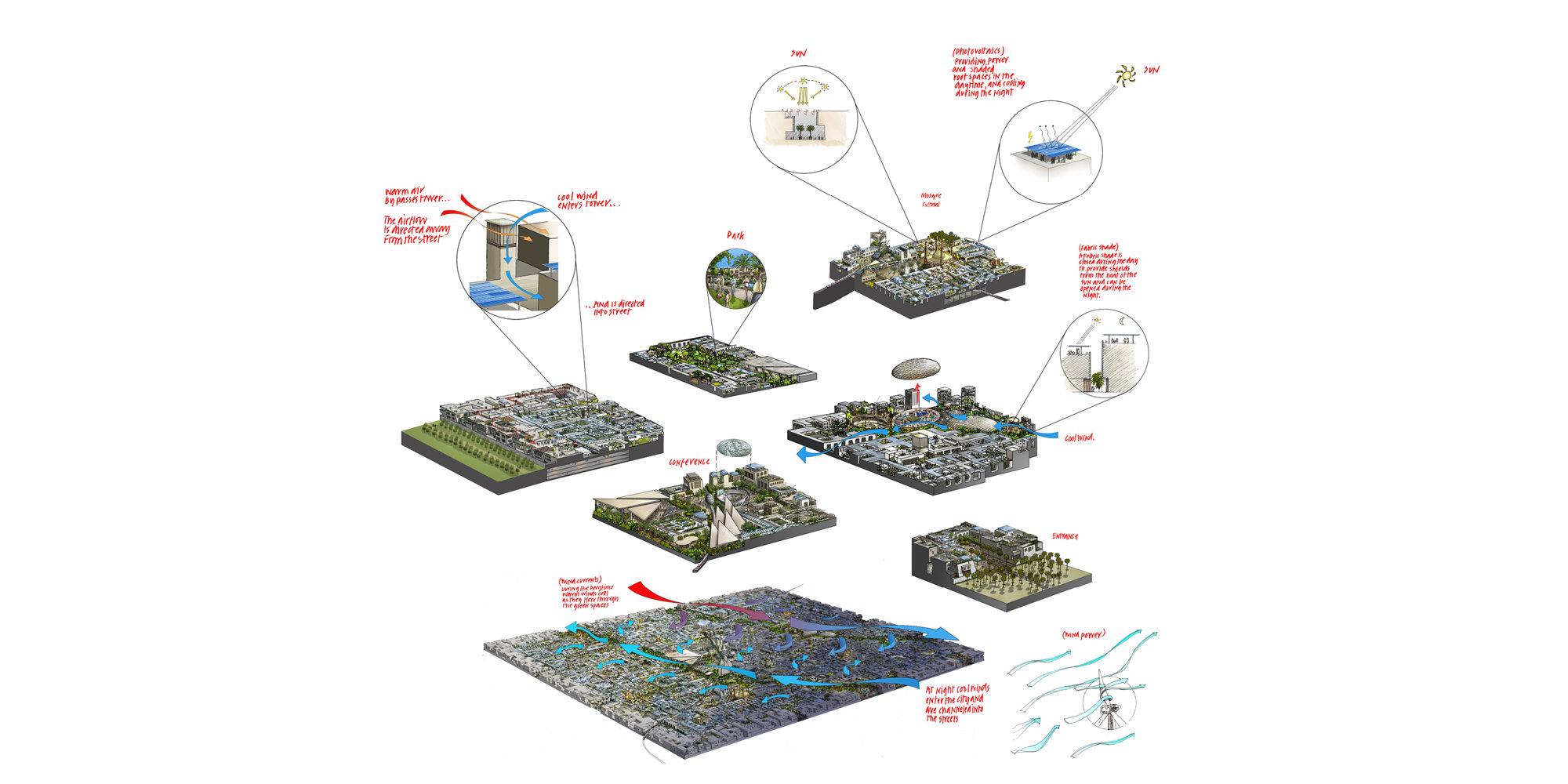

Today, Foster + Partners operates with a network of global studios, including those in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where the climate is not dissimilar to that experience by Fathy in Egypt. Despite his examples, following the popularisation of the automobile and mechanical cooling, the question of city building in the harsh desert climate has been largely answered by solutions that expend a vast amount of energy. The post-oil economic boom meant citizens desired greater comfort and convenience, and cities across the Arabian Peninsula met those needs with wide arterial roads to allow for free flow of traffic, sparsely populated gated suburban developments, and skyscrapers clad in glass curtainwalls that create harsh and out-of-scale urban environments. Masdar City reflects the ambition of Abu Dhabi and Foster + Partners to challenge the way contemporary urban developments take place in the region, by combining state-of-the-art technologies with the planning principles of traditional Arab settlements to create a desert community that aims to be carbon-neutral and zero-waste.

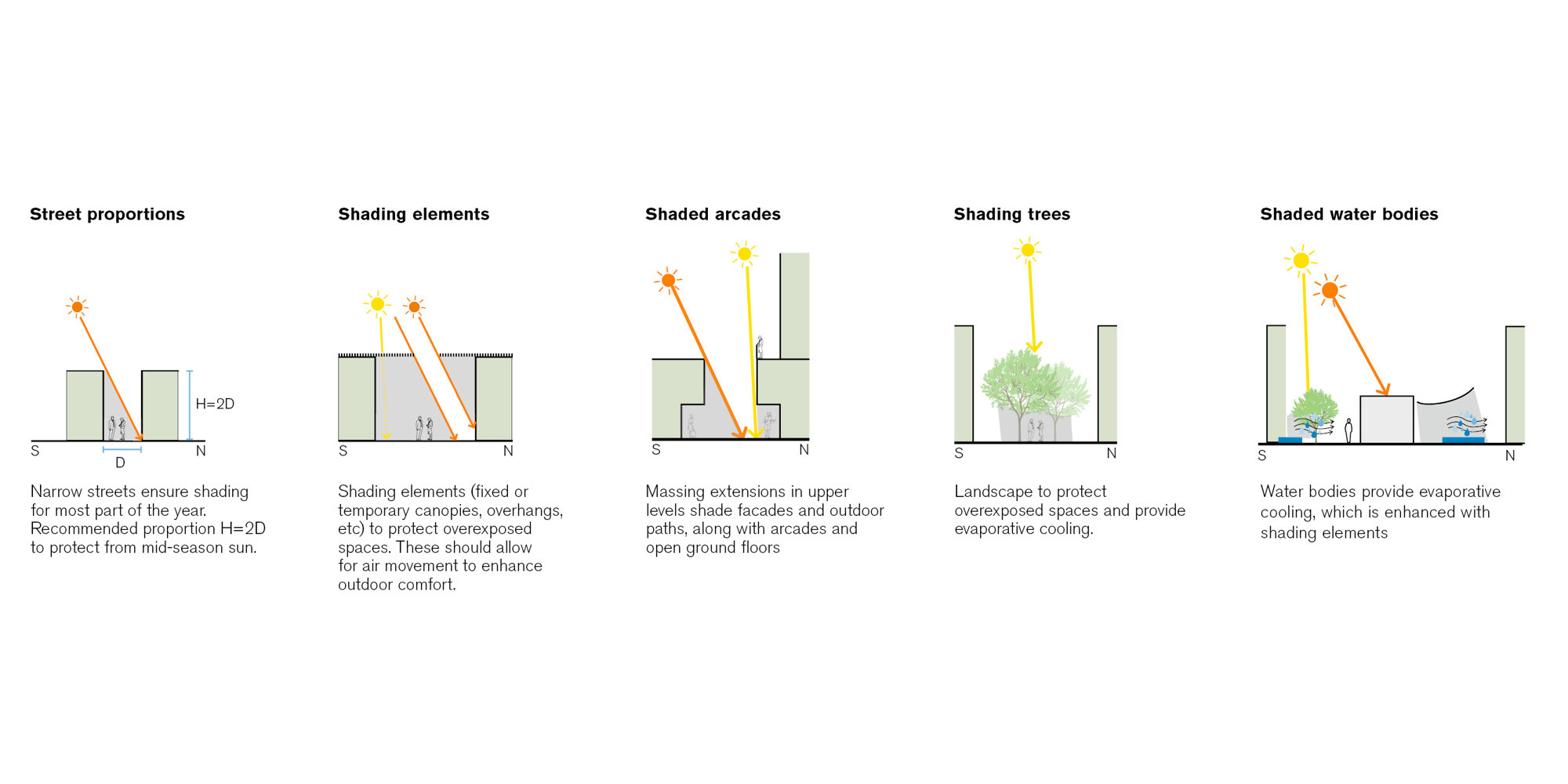

Masdar City is a mixed-use, low-rise, high-density development. The project aims to create a low-energy urban cluster by prioritising local climate and concerns and passive design strategies, often calling upon the lessons of vernacular architecture to achieve this. It demonstrates the application of bioclimatic principles at the urban scale, adapting the proportions and orientation of the city- from buildings to streets and blocks- to local climatic conditions.

The development incorporates narrow streets to provide shade for pedestrians, strategically oriented buildings to block hot winds, shaded facades using external screening devices, and thick-walled buildings to enhance thermal mass and store heat. Courtyards are designed to offer shade and allow controlled air movement and well-shaded water features are integrated to benefit from evaporative cooling which passively reduces ambient temperatures.

Thinking beyond the immediate architectural response to a climate enables innovative solutions at wider scale. For example, intense solar radiation occurs year-round in the UAE. While excessive radiation is not advantageous for occupant wellbeing, it does present a significant opportunity for renewable energy generation that can power buildings in the region, which is studied and implemented extensively in the design on Masdar City through photovoltaic energy. In this way, climate can be leveraged to support wellbeing and sustainability, even at an infrastructural level, through the support of energy generation used to power buildings.

Practitioners of a bioclimatic approach, though varying in region, typology, and perhaps even style, are all linked in their commitment to the climate context, which closely considers the relationship between materials, building form, and site. A bioclimatic approach, additionally, sought to make spaces that were comfortable and inviting. As Victor Olgyay spoke in a course lecture at Princeton:

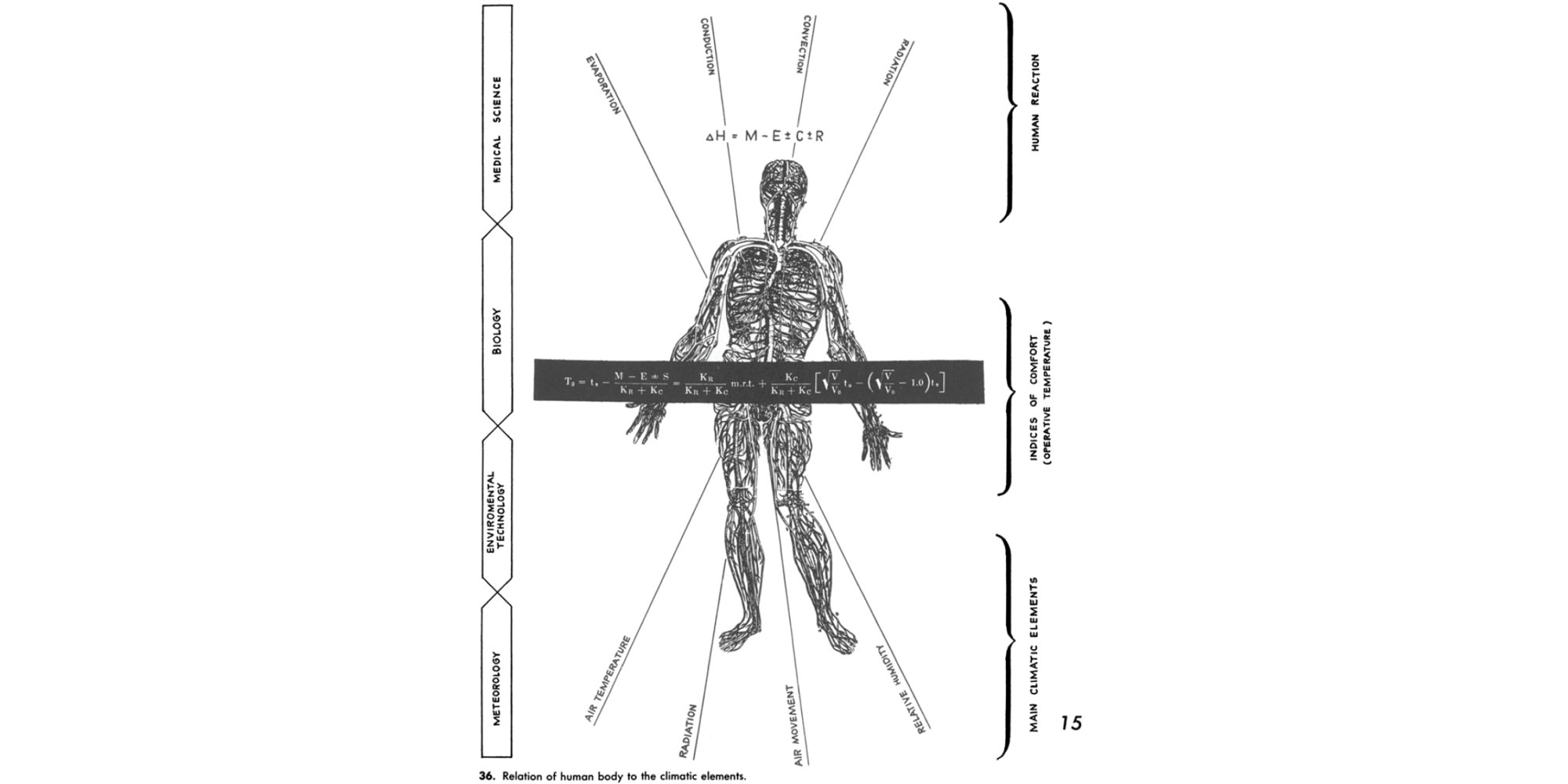

The primary task of architecture is to act in man’s favor; to interpose itself between man and his natural surroundings to remove the environmental load from his shoulders. The fundamental task of architecture is thus to lighten the very stress of life […] The thesis of this course [taught at Princeton] is that this interposition between man and his climatic environment […] is the psychological basis of health and comfort in architecture.

Olgyay’s ‘interpose’ imagines architecture as both a barrier between ‘man and his natural surroundings’ as well as an active link that constitutes ‘the basis of health and comfort.’ A bioclimatic approach, for Olgyay, is at once a means of protection from the environment and a means of connecting with it. In this way, architecture is neither hermetically sealed nor exposed but always changing in response to specific climates.

Relation of the human body to the climatic elements. Olgyay observed that ‘humans possess limited physical flexibility and adaptive capacities compared to many animals equipped with natural defences against various adverse climate conditions.’ It was the task of architecture to adapt, on behalf of the human, in a way analogous to passive heating and cooling that is demonstrated in biology and the natural sciences. From Design With Climate, Olgyay, V. (1963) 2015.

Perhaps, in the sixty years since Olgyay’s statement, a human-centric approach that acts in ‘man’s favor’ to remove ‘an environmental load’ can be productively challenged. The design community must acknowledge its deep implication in the climate crisis and take a lead for propelling both the profession and broader society toward viable solutions. Designing not just with but also for the climate – being ecologically protective and regenerative, actively restoring and improving the environment – is a choice we can make by introducing the climatic data and modelling into the early and ongoing stages of a design process.

The Bioclimatic Design Process

In Design with Climate, Victor Olgyay outlines a four-part bioclimatic approach, beginning with climate analysis, where temperature, humidity, radiation, and wind patterns are studied to establish an understanding of the climate and the site. This works alongside a biological evaluation which considers how people will use the space; this, in turn, considers what people in the region might wear, what activities they will participate in (whether working, relaxing, being active), and at what times of day the site will be used. This is followed by a third step, technical analysis, involving studies on site selection, orientation, shading, air movement, and temperature balance, ensuring iterative optimisation for seasonal adaptability. Finally, the fourth step of architectural application translates these principles into design elements. The bioclimatic design approach first optimises the integration of passive strategies, then integrates mixed-mode solutions before relying on active systems, ensuring both efficiency and resilience.

Architectural practice has greatly evolved since Olgyay’s publication, and the four-part structure that he suggested has expanded to incorporate new disciplines. The interactions between climate data, technological optimisation, wellbeing, and architectural design are strengthened, as our ways of designing become increasingly interrelated and interdependent.

These elements of bioclimatic design are also present in Foster + Partners’ integrated and sustainable approach to design, where environmental engineers and analysts, computational designers, material specialists, researchers, and sustainability experts collaborate with architects and urban designers to create a climate-sensitive project that responds to the constraints – and possibilities – of a site. Other elements of design such as urban and landscape planning, material research, and post-occupancy analysis – also enter the design process at Foster + Partners.

Bioclimatic Design in the Twenty-first Century

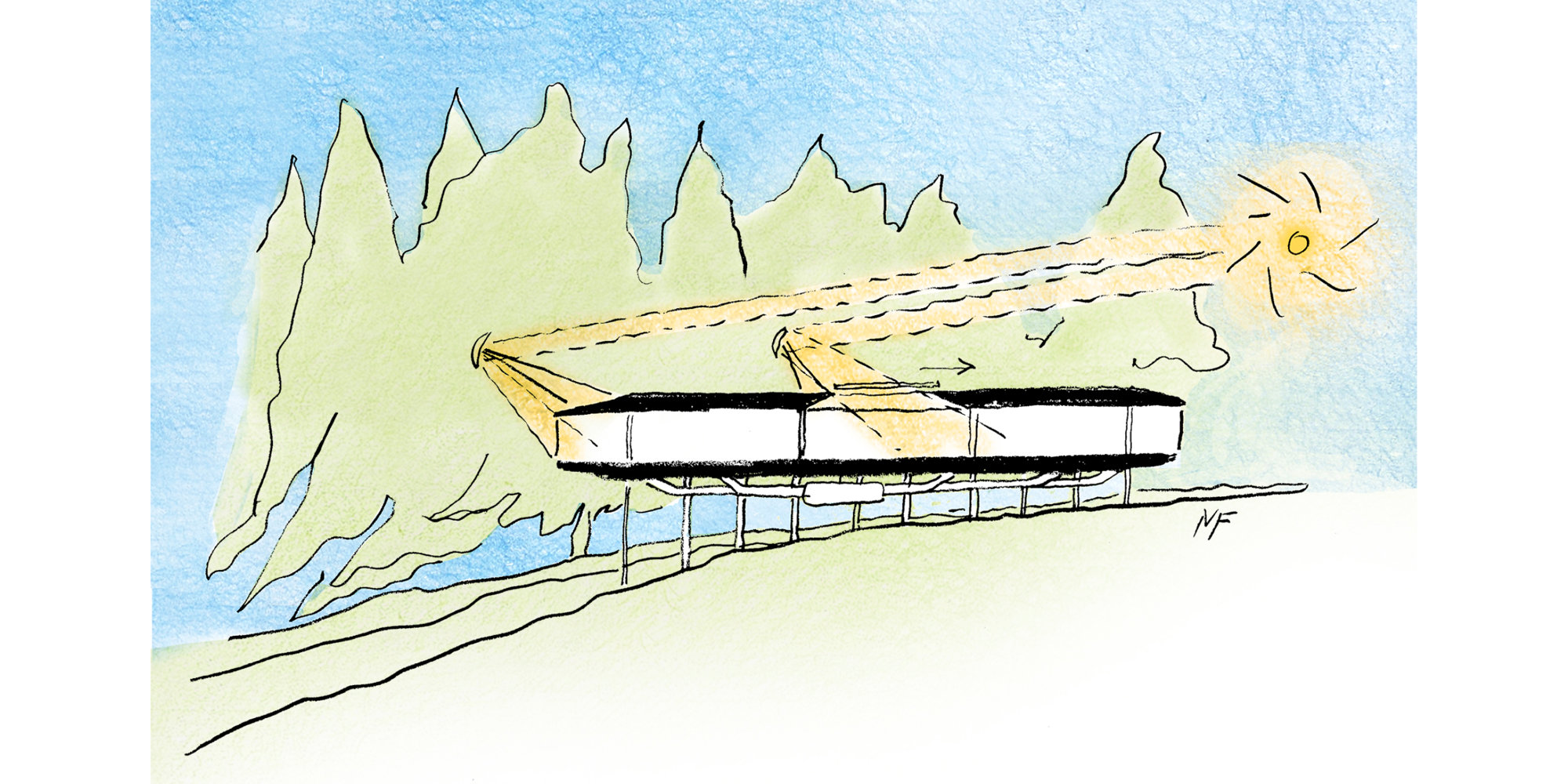

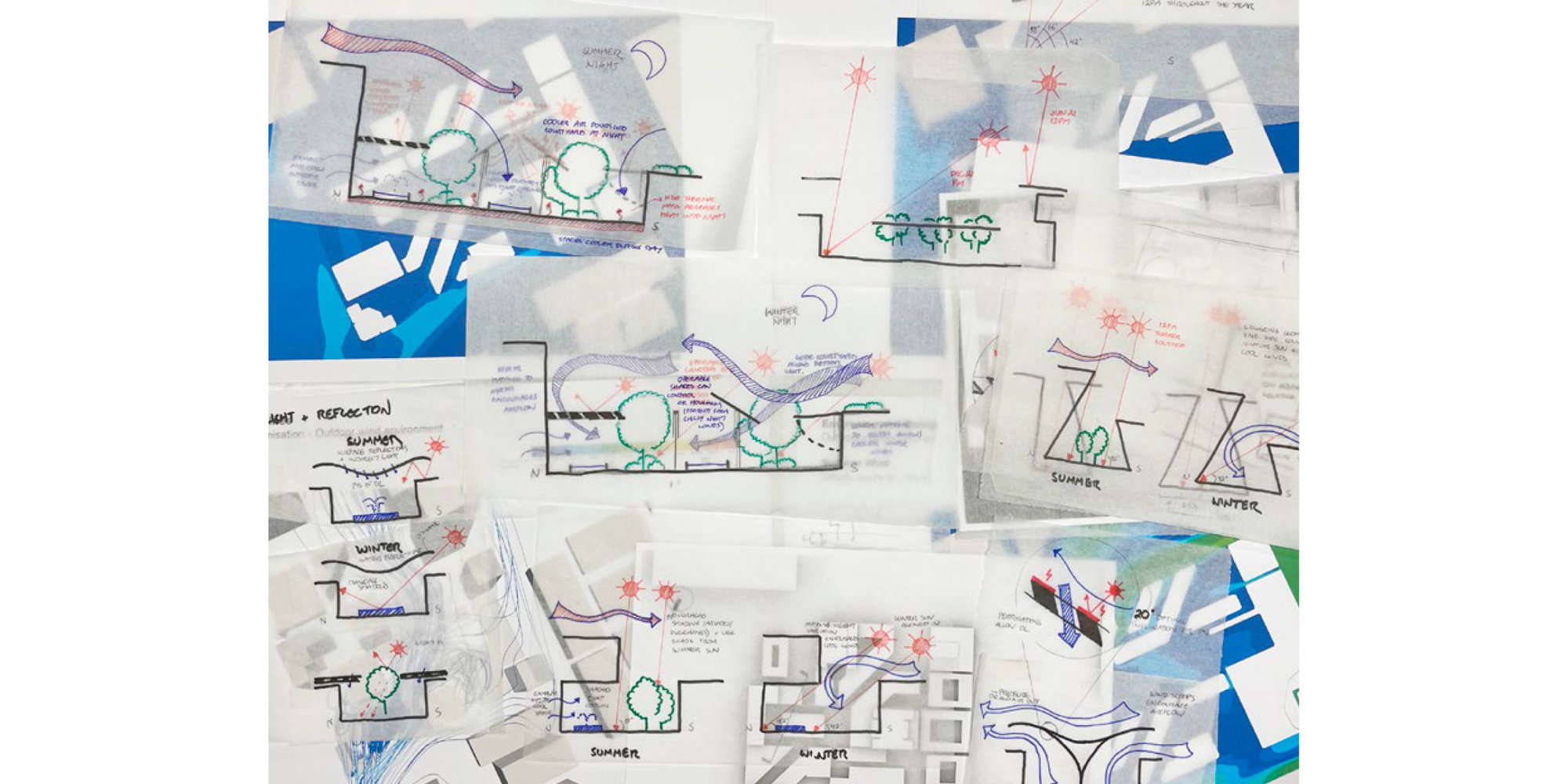

In the 1960 and ’70s, environmental design strategies at Foster + Partners were grounded in bioclimatic principles and explored through physical models, sketches, and intuitive design thinking. These early explorations were translated into guidelines and early analysis software was used to assess various parameters effecting design performance.

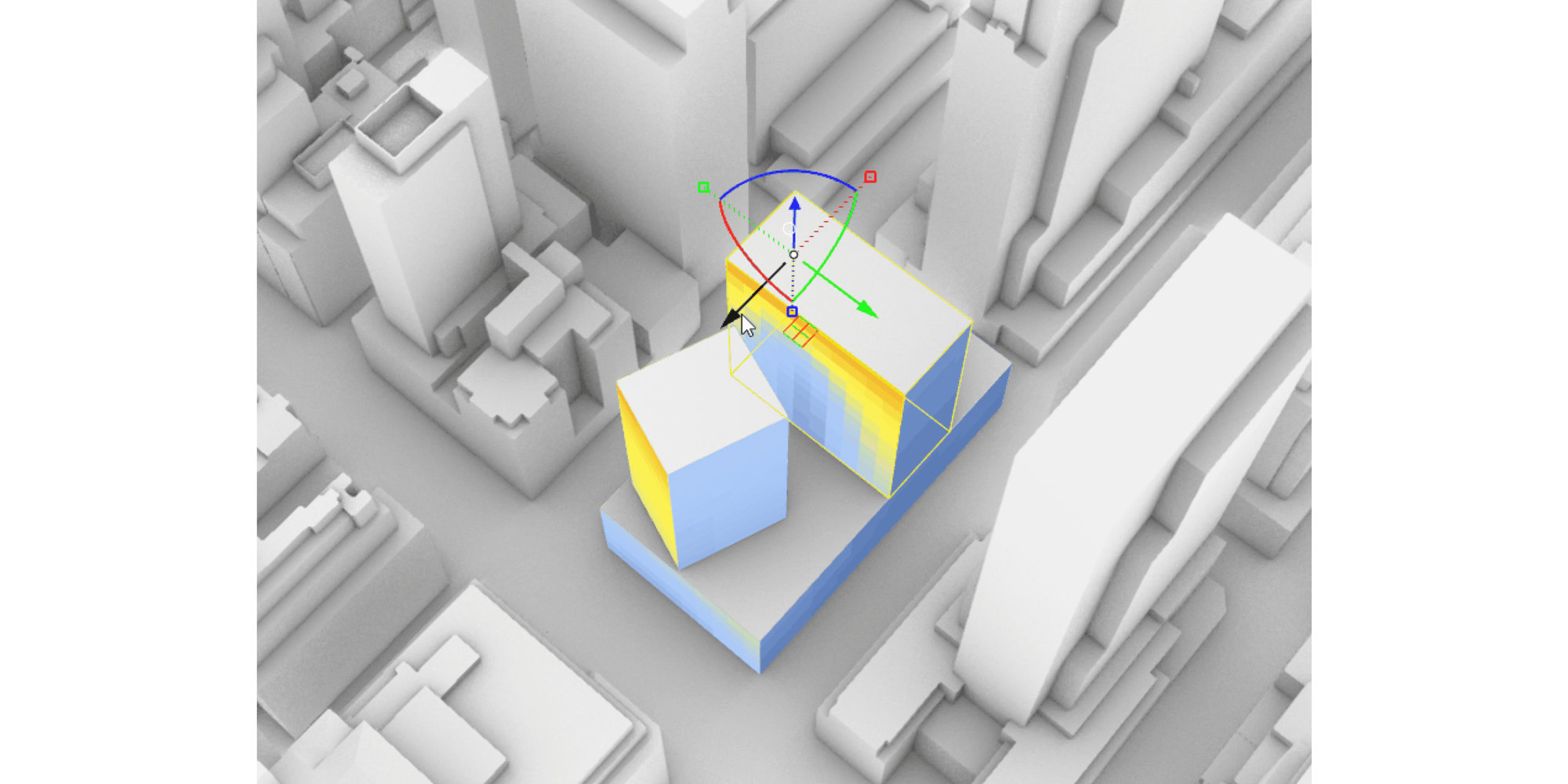

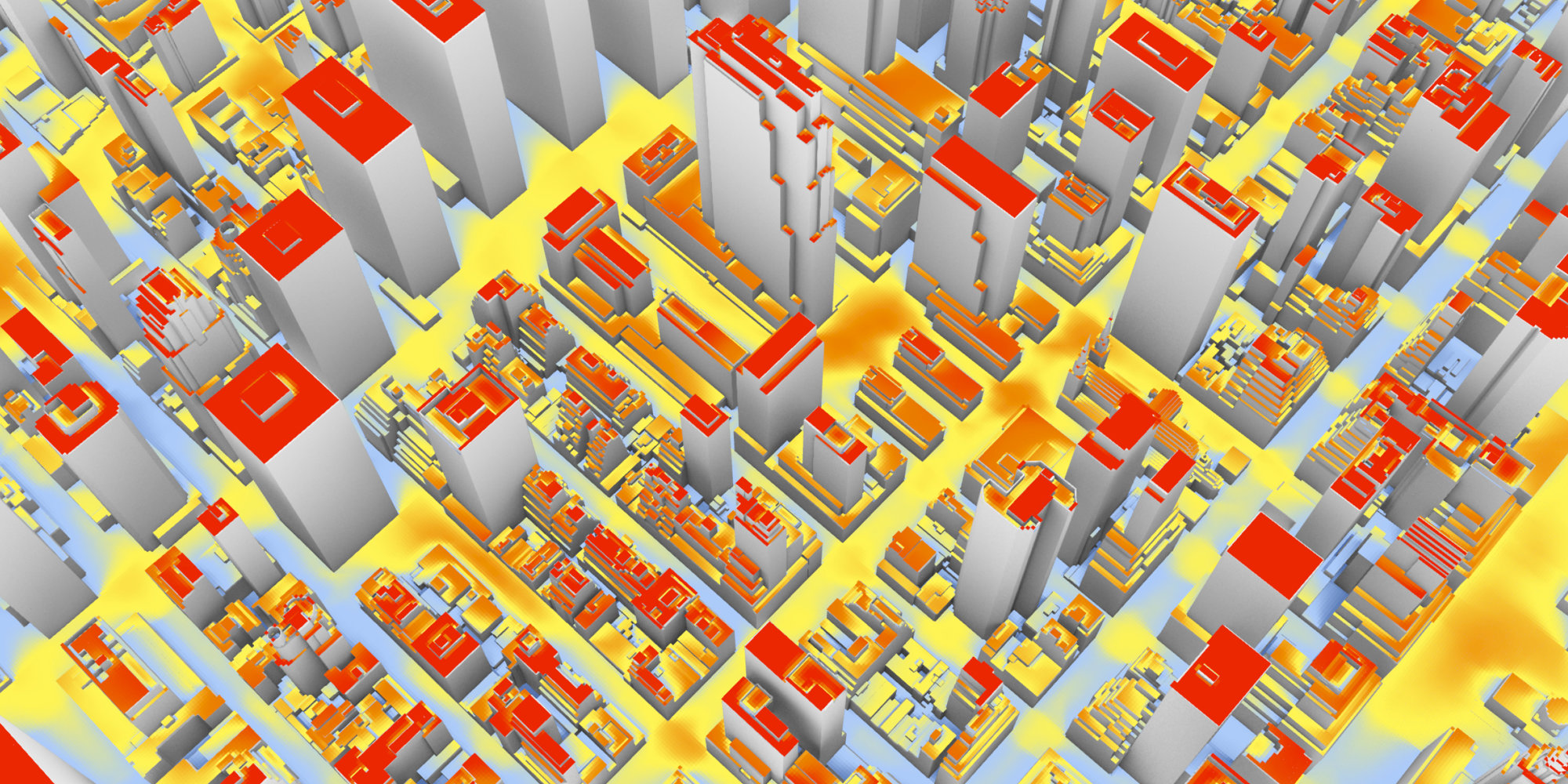

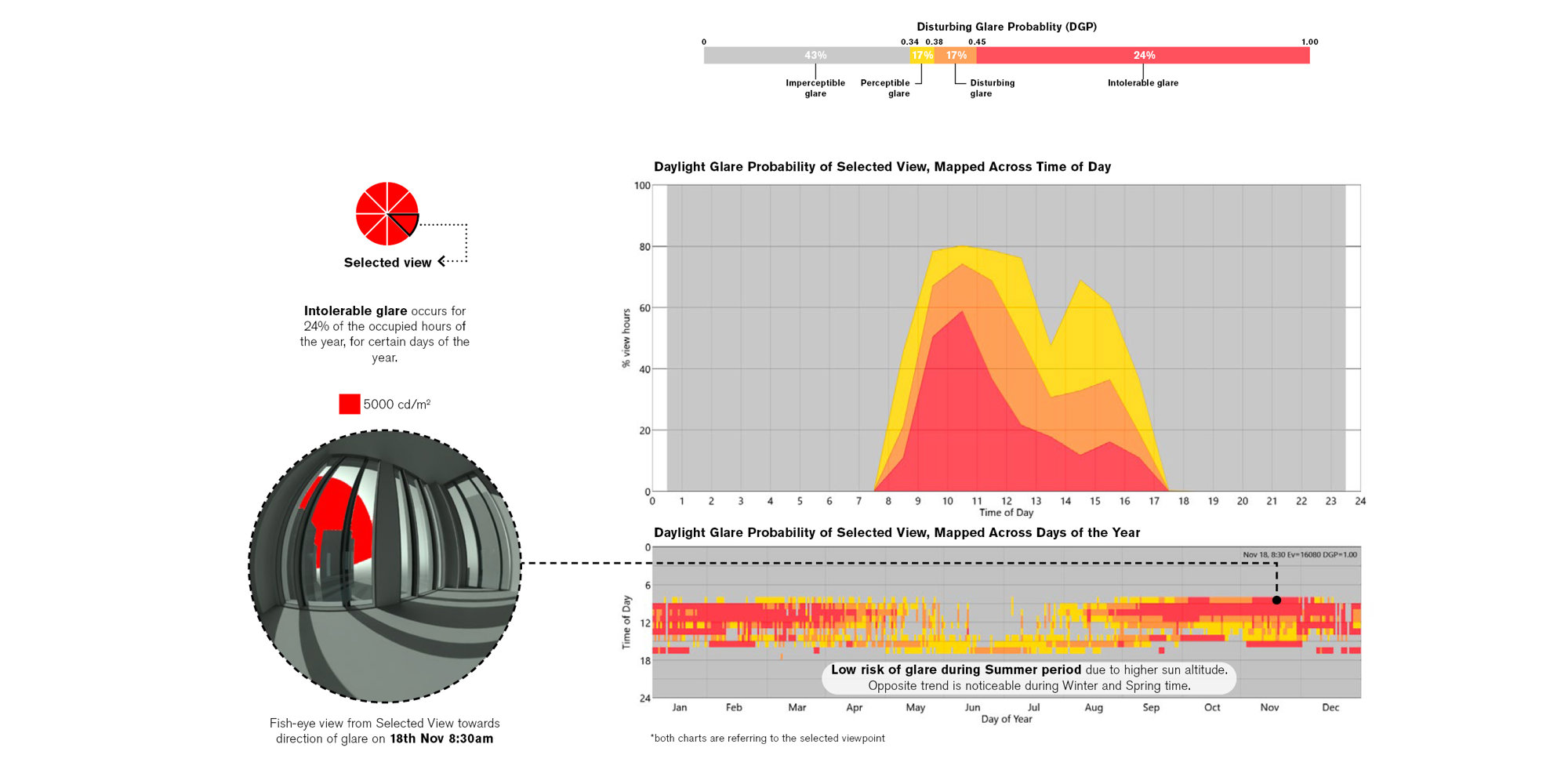

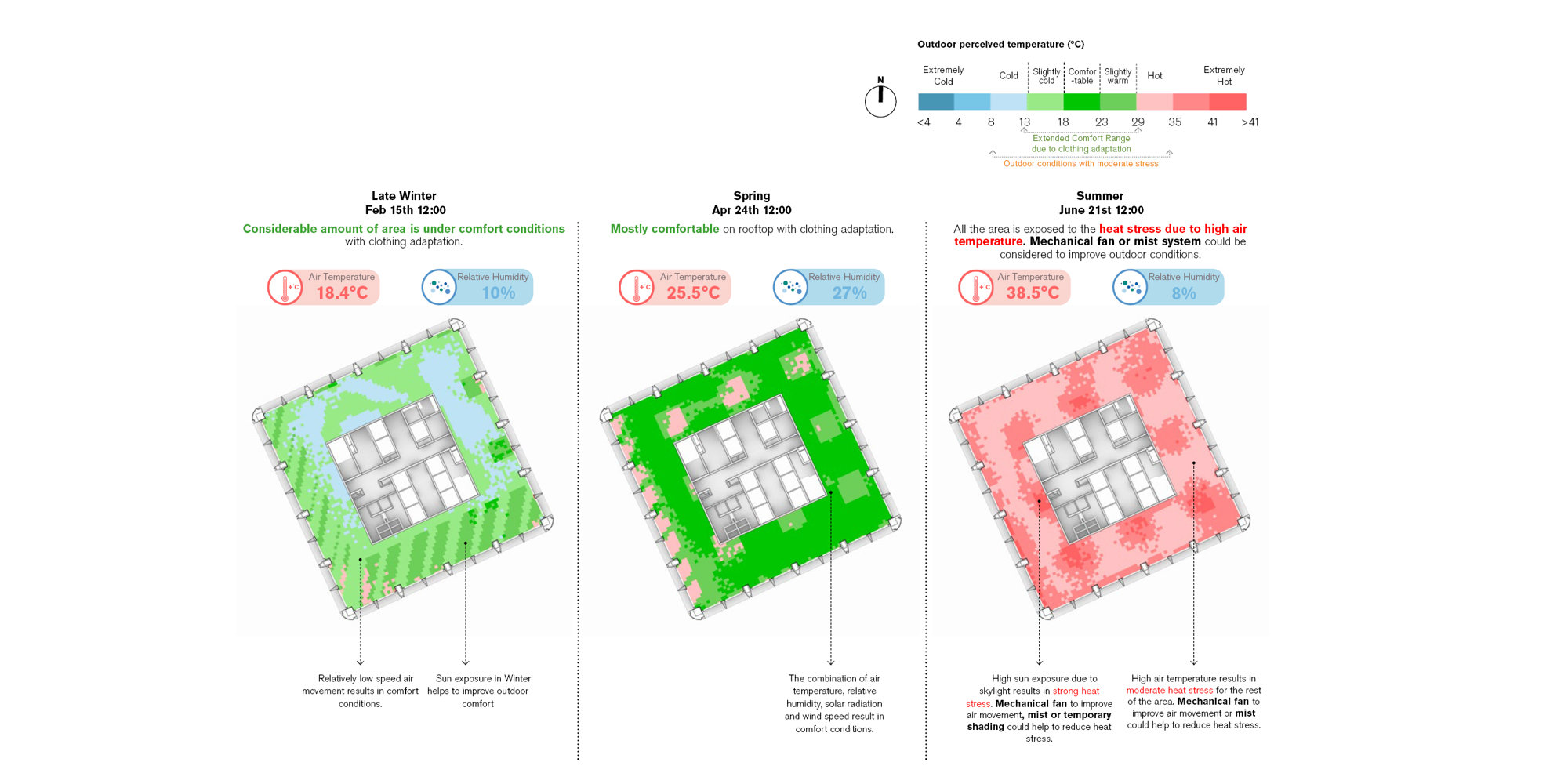

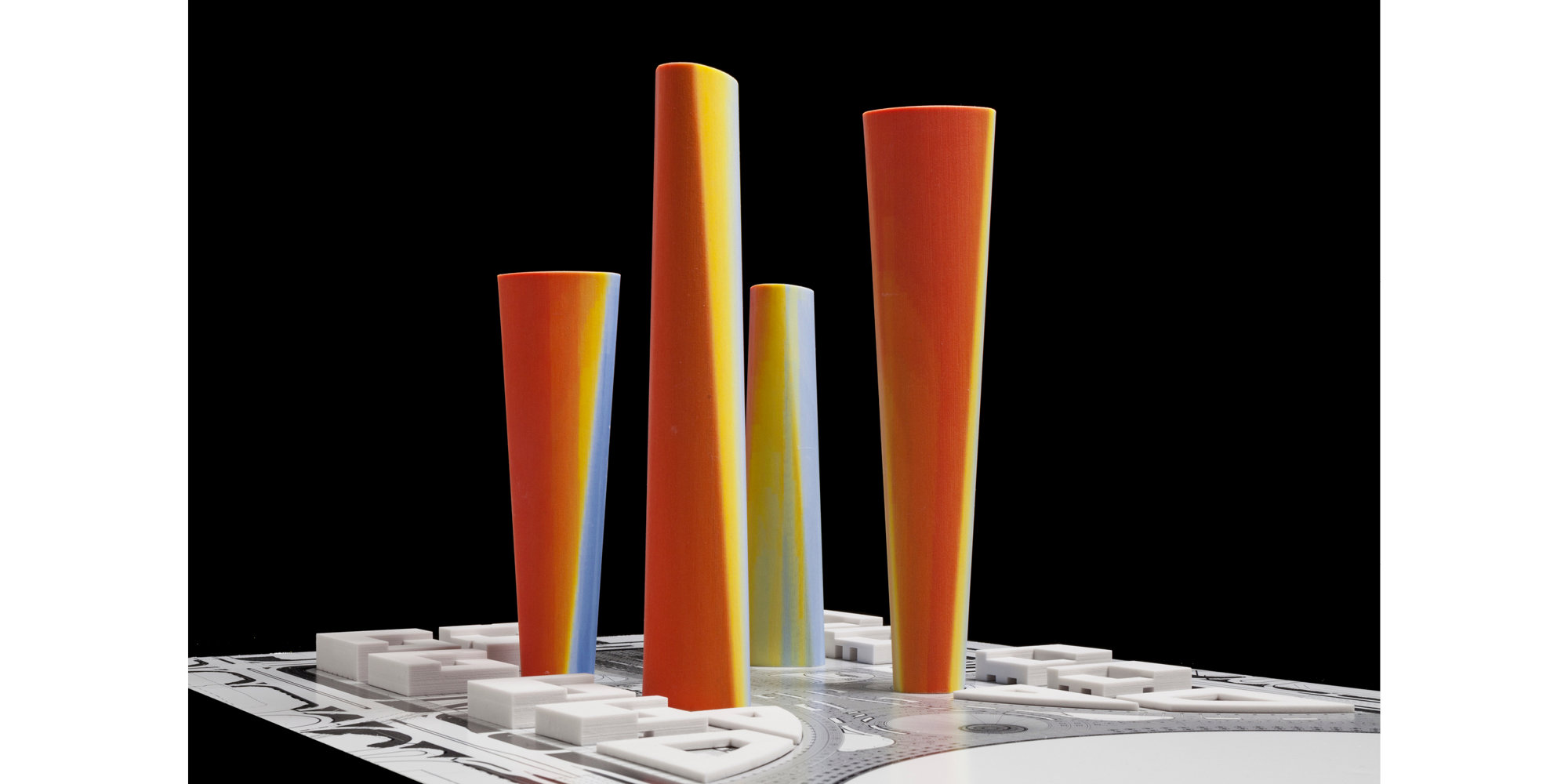

Today, computational tools are integrated from the earliest stages of the design process to assess factors such as solar exposure, wind patterns, and daylight access. A wide range of tools now enables designers to overlay climate data and design variants, testing multiple performance criteria parametrically. Creating sets of design guidelines for various climates, these tools support the development of climate-responsive standards by offering analyses on outdoor comfort, wind behaviour, facades, energy modelling and thermal performance.

A recent example of this integrated approach to sustainable design is Foster + Partners’ recent public launch of Cyclops. Programmed by the Applied Research + Development team to aid designers, Cyclops seamlessly integrates into existing workflows and enable iterative simulations that are fundamental for environmental analyses. Not unlike Olgyay’s analogue predictions for how to orient and shade an individual building according to the sun’s rays, Cyclops speeds- and scales-up the design process, to suit the pace and scope of a digitally led design world. By visualising climate databases in a 3D format, these tools enable more context-sensitive and climate-specific design analyses.

These insights guide design decisions that align with targets for resource efficiency, carbon reduction, and occupant health and wellbeing while responding to client expectations. Seamless collaboration between design and engineering teams enables a data-driven, evidence-based approach, with design options iteratively tested through simulations to determine the most effective and conceptually aligned solutions.

The Environmental Engineering at Foster + Partners deepen this approach as the project develops. Using an extensive library of climate data, the team perform detailed site-specific analysis to identify the strengths, weaknesses, potentials, and opportunities of the site with relation to it climatic context. These insights are then translated into design guidelines tailored to the project. These guidelines also consider ‘best practice’ standards set by Foster + Partners, as well as performance targets defined and guided by various international certification systems such as LEED, Mostadam, and GSAS. Certifications aligned with client aspirations give emphasis on passive design strategies with varying focuses such as energy efficiency, solar shading, and microclimate optimisation.

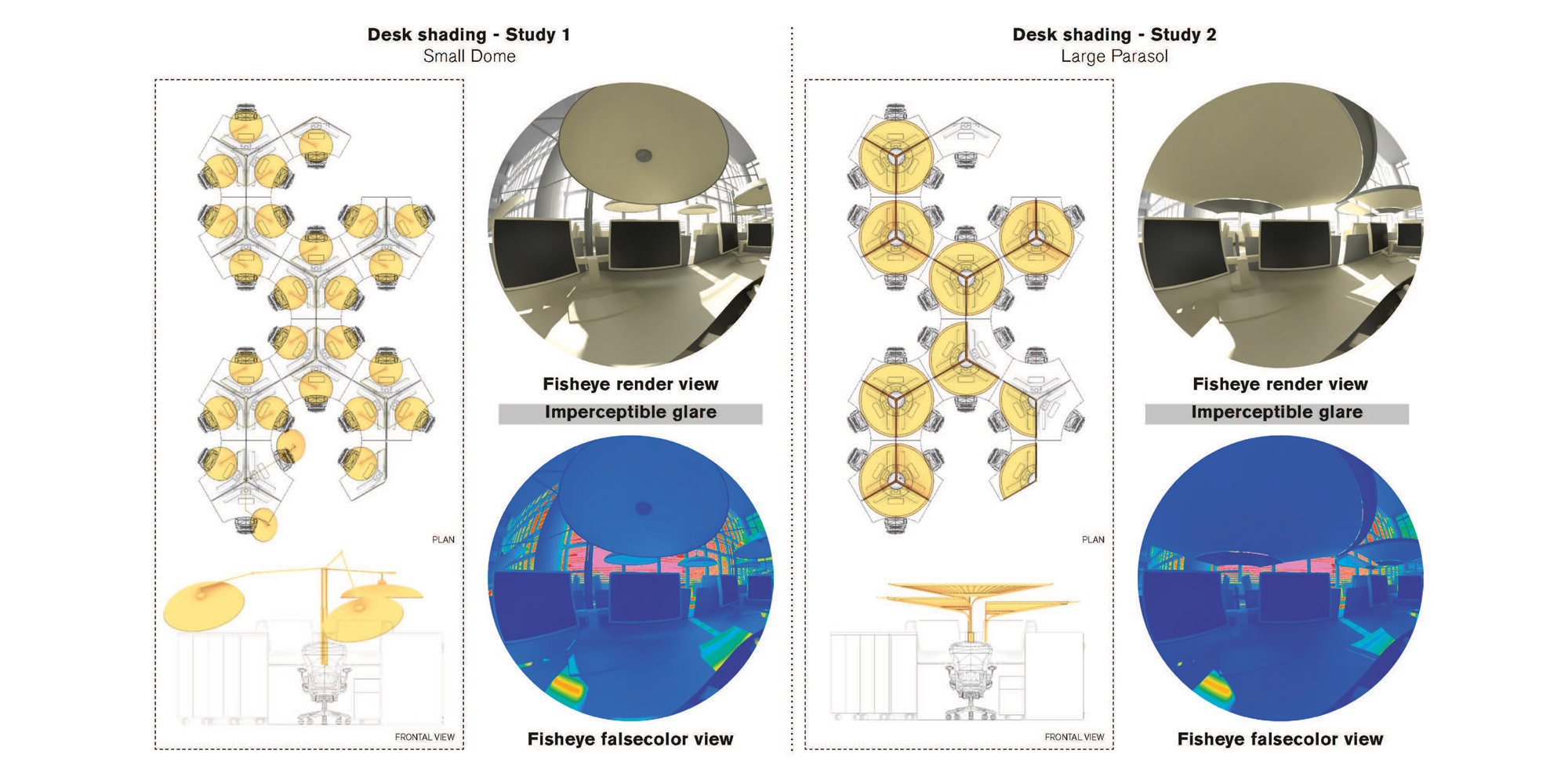

Each project involves focused and context-specific studies, which may include balancing daylight for occupant comfort, ensuring sufficient light for plant growth, or selecting materials based on environmental performance. Lessons learned from past projects play a crucial role in refining design strategies and improving systems and workflows. This ongoing feedback loop drives innovation, helping teams find a balance between performance goals and design implementation—from schematic design through to development and construction.

The emergence of Bioclimatic Design at Foster + Partners

Victor Olgyay was considered a pioneer of bioclimatic design in the 1950s and 60s, operating from the United States – namely, Princeton – at this time. Meanwhile, a young Norman Foster graduated from Yale University in 1962, to then form Team 4 in London in 1963, and later his practice, then called Foster Associates, in 1967.

Olgyay and Foster are professionally distinct, but the shared principles in their work – of the essential and unignorable link between building and climate, as well as a localised, data-driven approach to climate-sensitive design – can begin to conceptually and practically link the two architects of different generations, nationalities, and schools.

Echoes of the bioclimatic approach resound in a range of Foster + Partners projects, which have been designed across a variety of climates throughout the practice’s near-sixty-year history. Since Olgyay died in 1970 (relatively early in Foster’s career), the broader methodologies underpinning a bioclimatic approach have developed significantly. Heating, cooling, and energy generation technologies have become more efficient; instruments for measuring temperature, airflow, and light distribution have greatly increased in accuracy; models for predicting climatic patterns have become more complex, as have the datasets that they use; and research into wellbeing has substantiated links between the environment and physiological response. These developments, in turn, have informed a range of international projects completed by Foster + Partners.

The following case studies offer insights into how the practice demonstrates bioclimatic principles in its designs across temperate, desert, and tropical climates, in ways which extend – directly or indirectly – the work of bioclimatic architecture pioneers.

Ventilation Design: Commerzbank

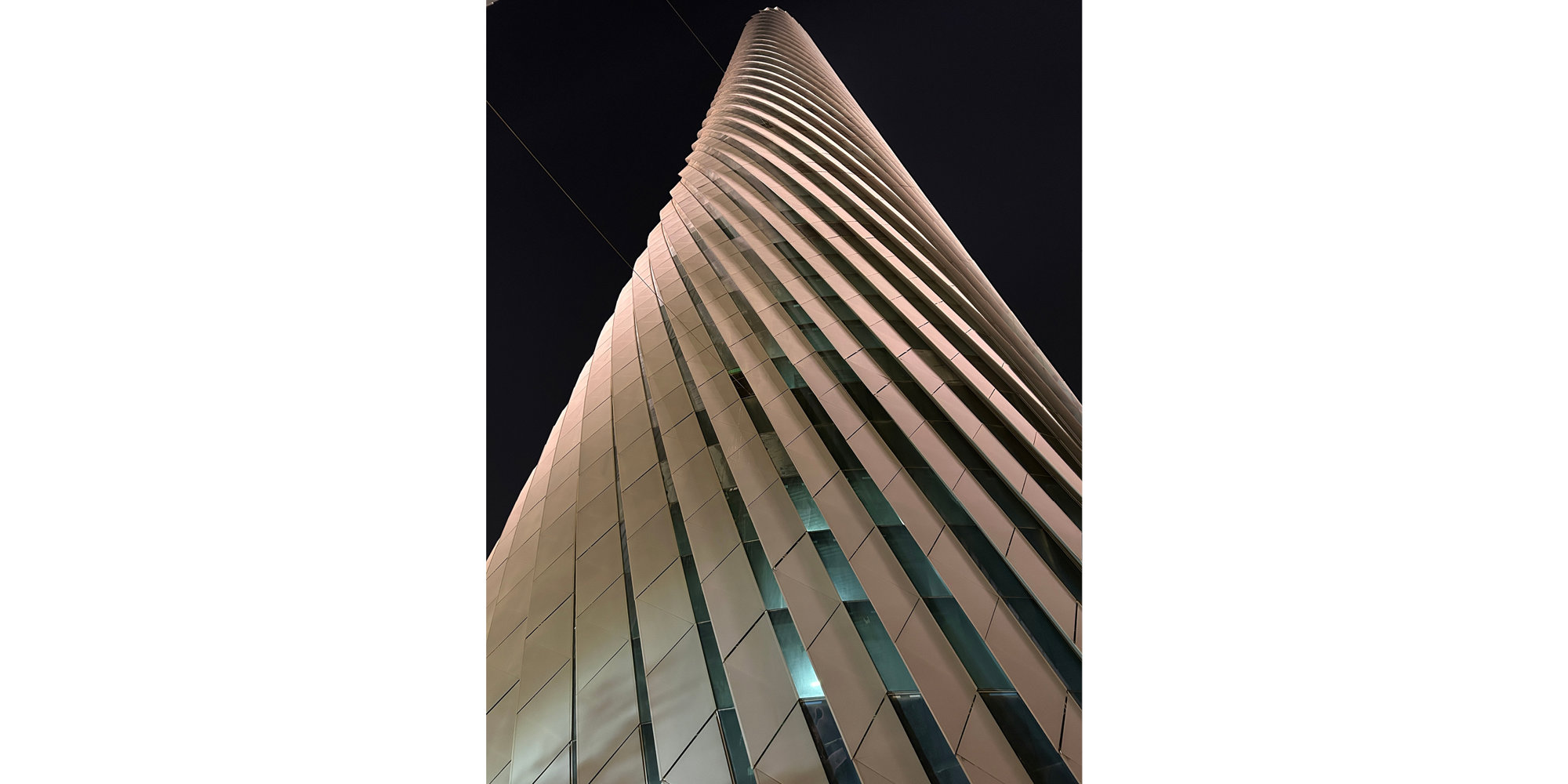

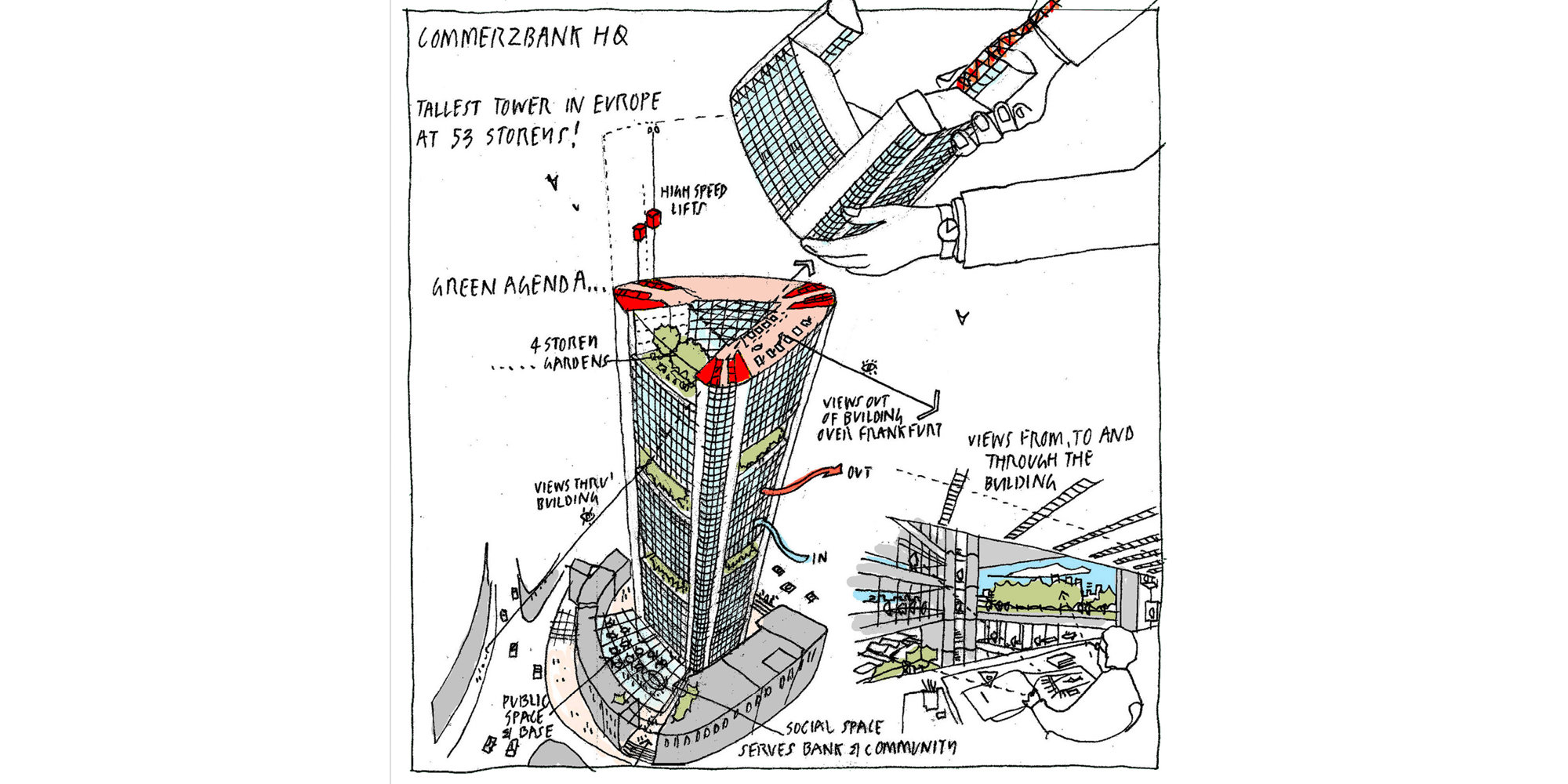

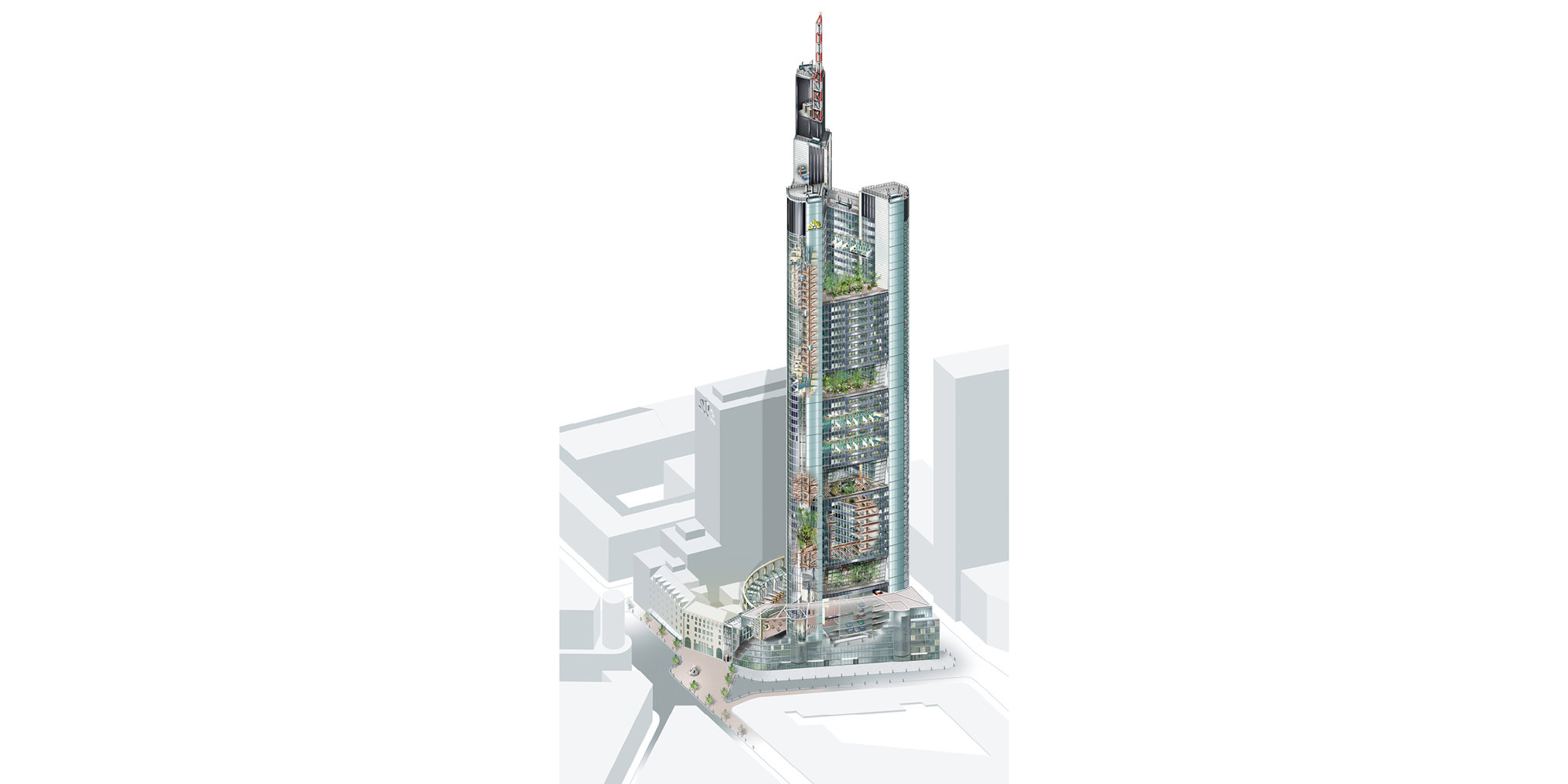

The Frankfurt-based office tower, which was completed in 1997, was the tallest in Europe at the time. It was designed when office spaces were being reimagined due to shifting work cultures worldwide. This high-profile office project was also, by leveraging site-specific conditions to inform design decisions, a bioclimatic building.

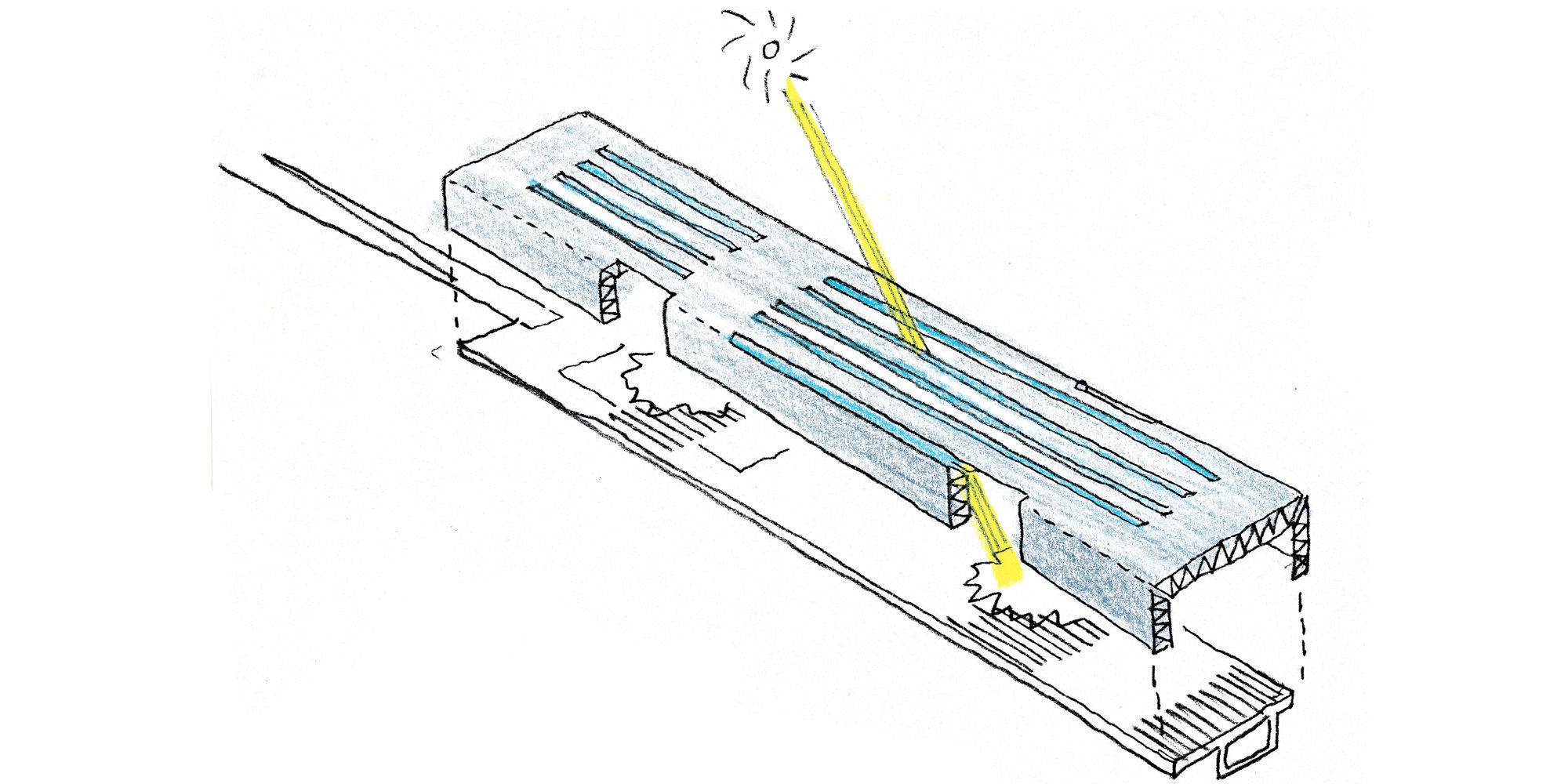

Frankfurt experiences mild summers and cool winters and has moderate wind year-round, with prevailing winds from the west and southwest. These conditions shaped the key design principle of the tower: every workstation should have access to daylight and natural ventilation.

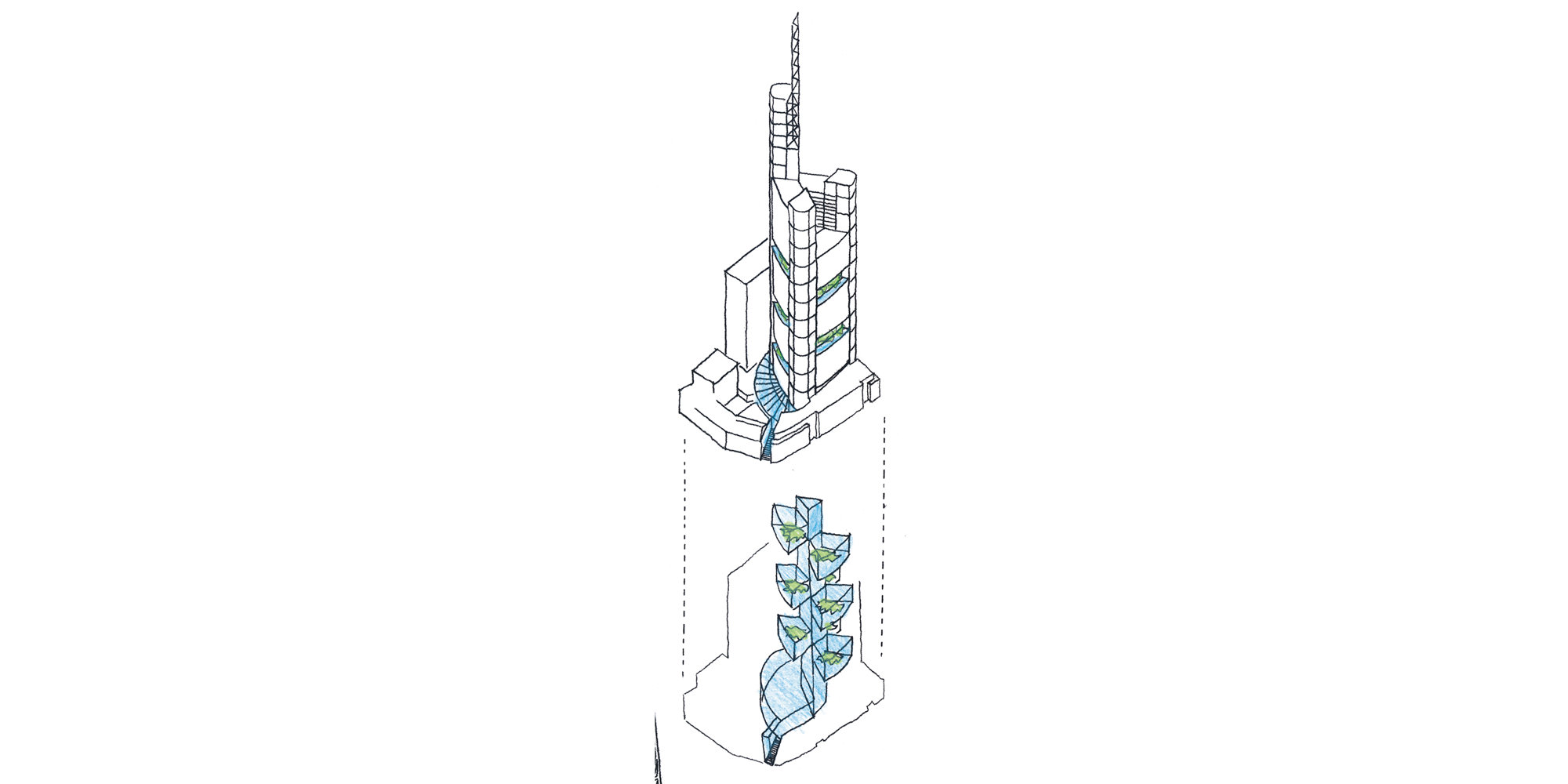

The building’s triangular form, comprising three ‘petals’ (office floors) and a ‘stem’ (the full-height atrium), is strategically oriented to take advantage of prevailing winds. The layout and spatial organisation are informed by climatic data to optimise environmental performance.

The atria enhance airflow during mild summers through a stack effect. The central atrium which spans the full height of the tower acts as a chimney that naturally moves warm air upward and out of the building. A series of four-story sky gardens rotate every 120 degrees up the entire building and allow air movement. These design considerations allow the building to adapt throughout the cycles of day and night, as well as seasonal cycles, and the diurnal differences of late spring, summer and early autumn.

Natural ventilation is allowed when the outdoor temperature is suitable, facilitated by a special glazing system that permits the intake of cool air while exhausting warm, heated air from above. In extreme weather conditions, where natural ventilation is not suitable, cooling is provided via chilled ceilings and heating through perimeter heating elements. Windows are integrated with the Building Management System (BMS) to ensure that mechanical ventilation operates only when the windows are closed.

The design also maximises daylight throughout the year, particularly during winter where increased cloud cover during winter reduces sunlight. Artificial lighting is linked to daylight levels and controlled by motion sensors. This significantly reduces the building’s energy consumption and therefore operational carbon, while also connecting occupants with the external, temperate climate.

Thermal Comfort and Responding to Orientation: Casa De Gobierno

Other designs have to adapt to a range of weather patterns occurring in the same region. Buenos Aires in Argentina has a subtropical climate characterised by hot, humid summers and mild, often rainy winters. Spring and autumn bring changeable, often stormy weather, primarily due to shifting air masses, meaning that the city is highly vulnerable to flooding during these periods of heavy rainfall.

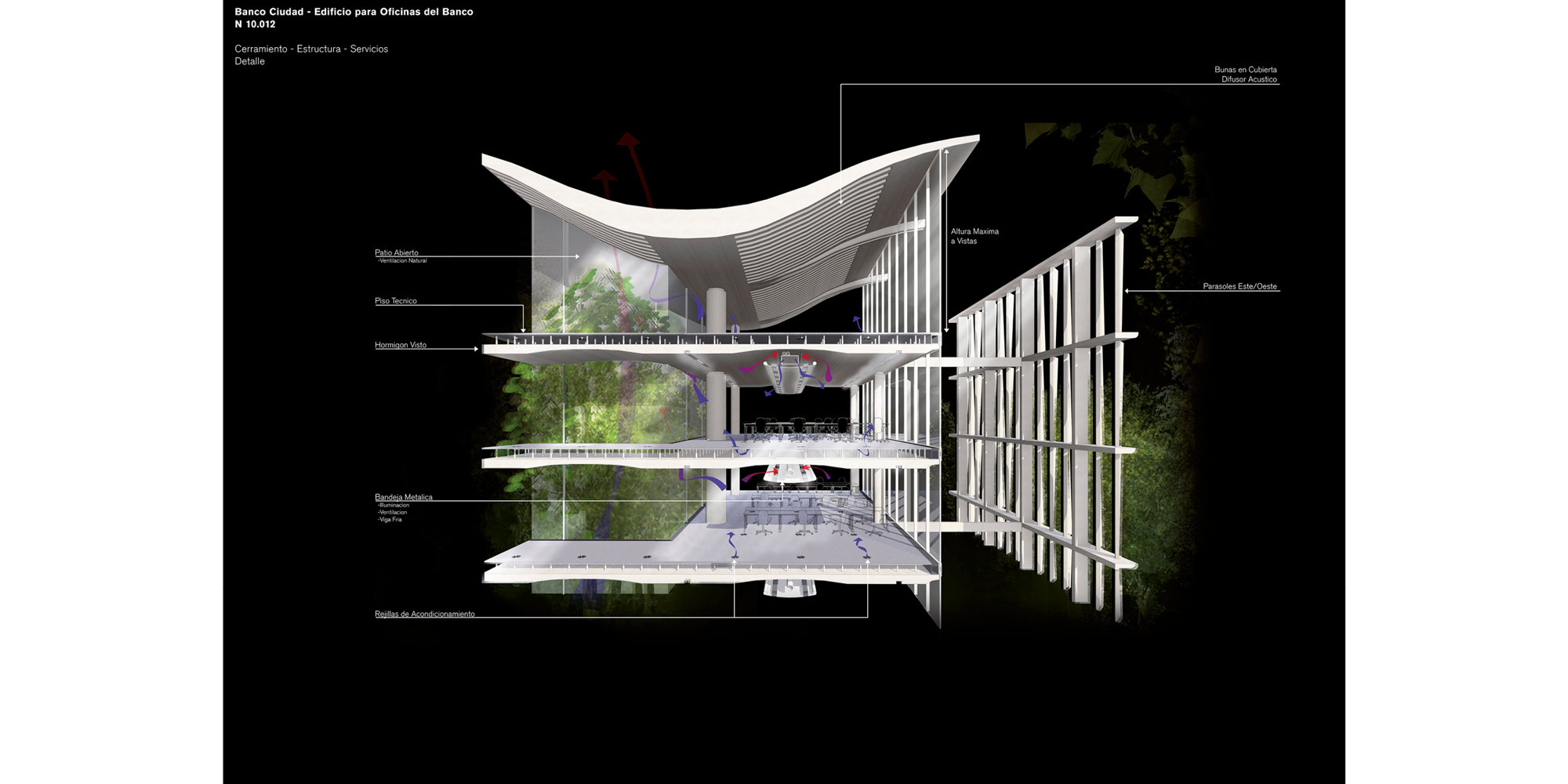

Foster + Partners’ design for Casa de Gobierno, a new city hall for Buenos Aires, addresses the local climate and the surrounding neighbourhood by prioritising heat mitigation and occupant comfort. The building reflects the neighbourhood's identity through landscaped courtyards. To provide year-round comfort, covered walkways offer shade and shelter from rain and excessive heat.

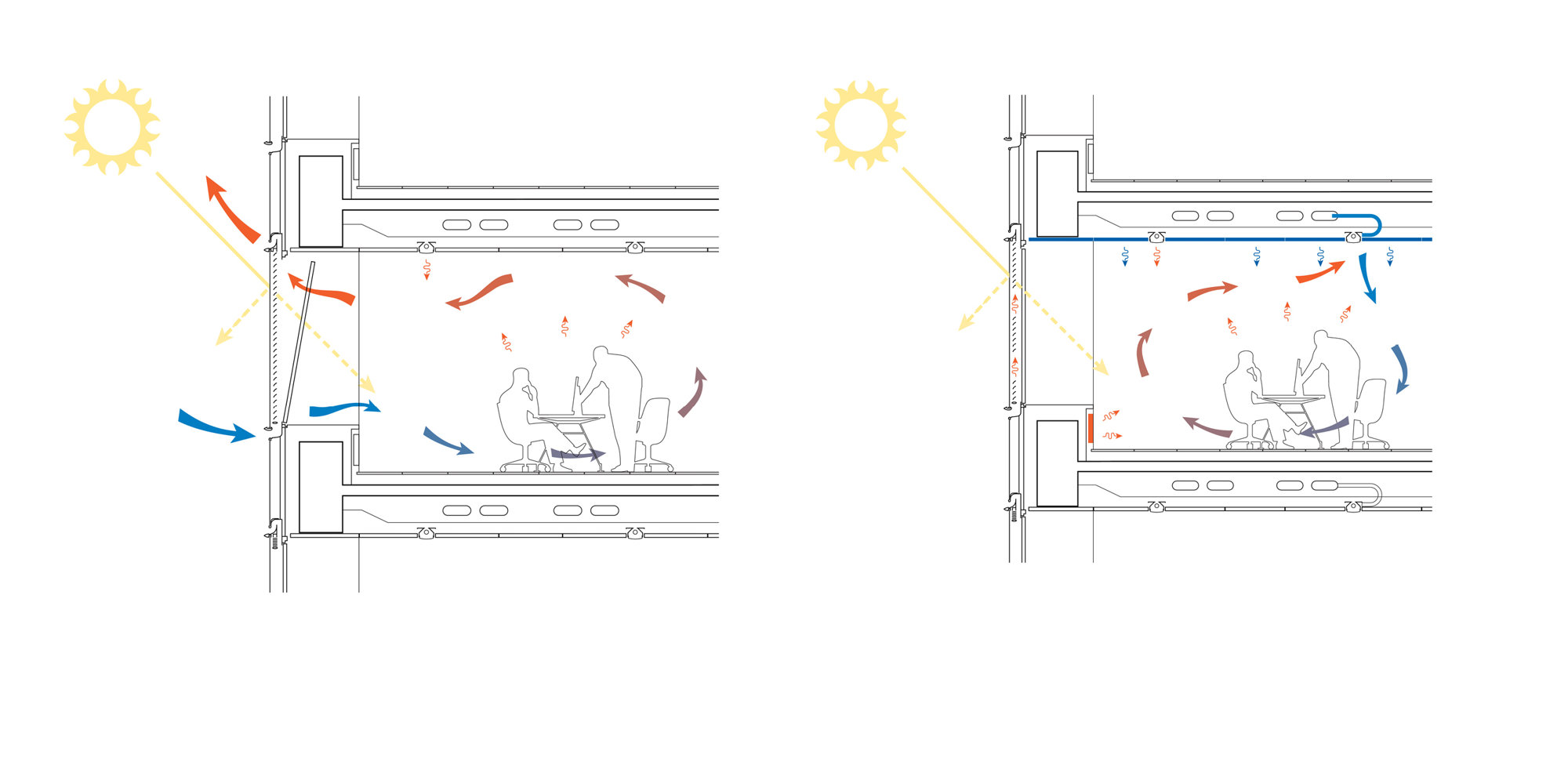

Vertical louvres along with a massive roof canopy passively mitigate heat and cool the large-scale building. The thermal mass of the concrete soffits, combined with displacement and chilled-beam ventilation system, helps regulate indoor temperatures naturally, especially in keeping the offices cool during the warmer seasons. A combination of ventilation strategies has been adopted. Considering the full spectrum of potential approaches, from natural ventilation to HVAC, the system is specifically designed to suit local conditions and ensure effective humidity management through passive and active means.

The facade design responds to the local climate and is evident in how the different orientations are treated. The eastern and western elevations are shaded by a continuous screen of louvres that rise to the full height of the building, providing effective protection against low-angle sun and minimising excessive solar gains, while the southern facade uses a canopy This recalls one of the core principles of bioclimatic design: each architectural detail requires tailored design responses. The design challenge lies in unifying these varied details into a coherent architectural expression.

Bioclimatic Futures

Today, climate considerations are emphasised across industries, particularly in the built environment, owing to improved access to climate data, advanced computational tools, and the support of sustainability-focused policies and performance targets. Similarly, occupant wellbeing has become a primary concern for both clients and building users.

The bioclimatic approach advocated by Olgyay, along with the climate-specific design philosophies of Hassan Fathy and others in opposition to the International Style, highlights the enduring relevance of designing with local climate, materials, and culture in mind. Their emphasis on integrating passive and active systems while drawing from vernacular traditions and supporting sustainable urban development remains vital – albeit with a twenty-first century framing. Foster + Partners are part of this discussion, having fused environmental engineering with technological innovation throughout its history.

Bioclimatic principles have long been integrated in the design process at the practice for a wide range of projects, across a wide range of climates. Driven by growing curiosity and deepened by investment into tools and research, including emerging machine-learning applications, Foster + Partners has – and continues to – explore the practical applications of climate-specific design. Design must consider the climate and lead us towards sustainable and imaginative futures.

Author

Neva Beskonakli

Author Bio

Neva Beskonakli is an Environmental Designer at Foster + Partners, specialising in climate-responsive design and sustainable urban development. She holds an MArch from the Architectural Association and has a background that bridges architectural design and building physics research. Her work spans multiple scales, focusing on the integration of data-driven strategies and computational analysis to enhance building performance, resource efficiency, and occupant comfort. At Foster + Partners, she is part of the Environmental Engineering team, contributing to the design of high-performance, climate-resilient environments through the application of advanced environmental design strategies.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George